It seems like everyone in the music world has opinions about the music of John Cage. Some people love his work, while others loathe it.

Regardless of how you feel, it’s always a great idea to learn more about any composer who engenders such strong responses in people.

Here’s our beginner’s guide to this fascinating composer.

John Cage’s Childhood

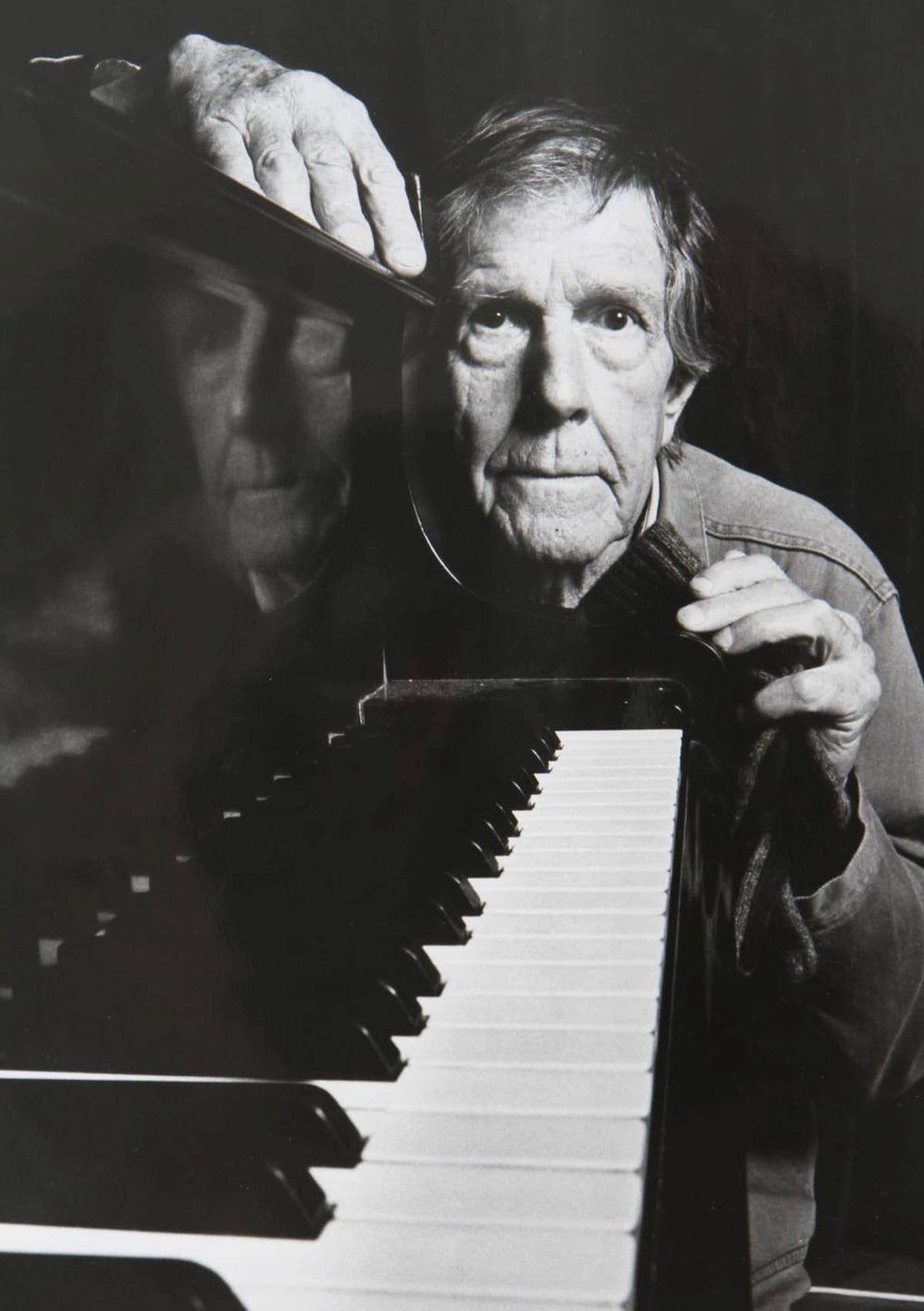

John Cage

John Cage was born on 5 September 1912 in Los Angeles. His mother was a journalist and his father was an inventor.

His father once famously told John, “If someone says ‘can’t’, that shows you what to do.” Cage would carry this fierce contrariness with him throughout his career.

He studied music and piano casually as a child, but he had other stronger passions. Originally, he wanted to be a writer.

He was an academic overachiever and graduated valedictorian. While in high school, he gave a speech at the Hollywood Bowl, advocating for a day of quiet, in which Americans would say nothing in order to better understand what others are thinking. This, of course, prefigured the entire philosophical concept behind 4’33”.

College Years and European Travel

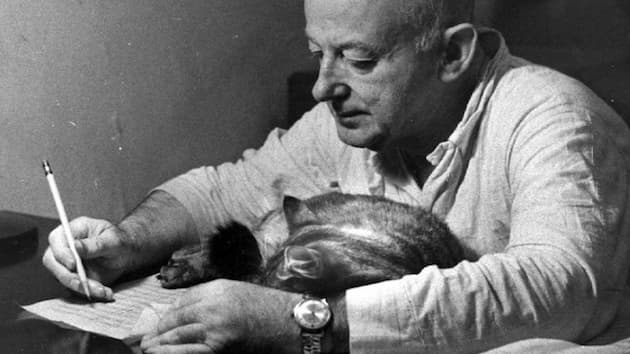

Henry Cowell

Cage enrolled in college in 1928 to pursue a theology degree but dropped out in 1930 because he believed the college experience “was of no use to a writer.”

Instead of finishing a degree or getting a job, he left for Europe on a trip funded by his parents.

In Majorca, he began composing for the first time. He also read Whitman’s seminal poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which reinvigorated his appreciation for his American identity, and convinced him that he wanted to create American art. He returned to his homeland in 1931 and began making his living lecturing about contemporary art.

He studied composition with Henry Cowell in New York and Arnold Schoenberg in California. Schoenberg was never particularly impressed by Cage’s musical ability, actually declining to call him a composer at all, but he did label him “an inventor – of genius.” Cage was very satisfied with that characterization.

Meeting His Wife and His Early Career

Xenia Cage

During his studies with Schoenberg in the mid-1930s, Cage met an artist named Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff, a glamorous, talented surrealist sculptor. He proposed on their first date, and they were married in 1935.

In the late 1930s, Cage worked as a dance piano accompanist at a college in Seattle. Here he befriended a choreographer named Merce Cunningham. Cunningham would play a very important role in Cage’s life.

In 1940, when he was playing in a room in Seattle too small to fit all of the percussion instruments he wanted to use, he invented prepared piano: i.e., playing a piano that has objects nestled in the strings to give the instrument a particular sound. He would become famous for his compositions for prepared piano.

In the spring of 1942, he and Xenia made a fateful move to New York. There he met famous New York-based artists of the era like Duchamp, Mondrian, and Pollock.

Unfortunately, he snubbed his patron – Peggy Guggenheim of the Guggenheim Museum – by scheduling a concert at the Museum of Modern Art instead of the Guggenheim Museum. She cut him off.

To make matters worse, his and Xenia’s relationship was deteriorating. He also ended up becoming romantically involved with his friend Merce Cunningham. Cunningham and Cage got together, and they remained partners until Cage’s death.

Influences on Cage’s Music

It was around this time that Cage became interested in Buddhism and Indian thought. These ideas would become lifelong influences on his art and music.

In 1951, a student gifted him a copy of the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination text. Cage decided to try using this in his music, including “Music of Changes” for piano and “Imaginary Landscape No. 4 for 12 radio receivers.”

John Cage: Imaginary Landscape No. 4

In 1952, he wrote (some would put air quotes around the word “wrote”) his most famous work: 4’33”. This referred to the length of time that the performer was asked to just remain still. The music, Cage said, would come from the ambient sounds all around the performer and listeners.

John Cage: 4’33” / Petrenko · Berliner Philharmoniker

Making a Splash

Not surprisingly, these works were all gaining him a reputation. His star continued to rise, and by the mid-1960s he was getting so many commissions, he had to turn many down. He also traveled a lot, overseeing performances of his new and challenging works.

In 1969 he wrote HPSCHD, which featured no fewer than seven harpsichords playing music created by chance.

Vischer, Bruce & Tudor (harpsichords, tapes) John Cage & Lejaren Hiller HPSCHD

The same year, he wrote “Cheap Imitation” for piano, which was the first fully traditionally notated work he’d written in ages.

John Cage / Cheap Imitation (1969)

Later Life and Death

In the 1970s, his health deteriorated, and he found himself dealing with debilitating arthritis and chronic pain. Writing his musical manuscripts out by hand, as he preferred, became difficult. Seeking a new outlet, he began experimenting with writing poetry.

Cage’s bad health continued to worsen in the 1980s, and he even had a stroke. After a second stroke in August 1992, he died.

Cage’s Legacy

John Cage about silence

The life and legacy of composer John Cage stand as a testament to both creativity and controversy.

His work challenged the very definitions of what work and art could be, pushing boundaries and daring audiences to embrace the unexpected.

John Cage and his prepared piano

Moreover, beyond his music, Cage’s philosophical musings on the nature of sound and existence continue to resonate with thinkers and creators across disciplines.

Love him or loathe him, John Cage’s influence will shape the world of music and art for generations to come.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

John Cage also composed many traditional pieces for violin and piano that are fun to play and very beautiful to listen to. These are often overlooked in commentaries.