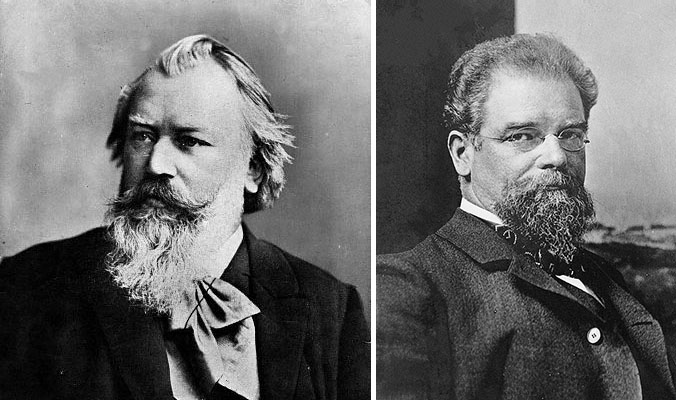

C. Brasch: Johannes Brahms (1889)

Nicola Perscheid: Max Klinger (1900)

The German symbolist artist Max Klinger (1857-1920) took inspiration from Brahms to create his Brahmsphantasie, a book of music and images that took Brahms’ music to a level never before seen.

In his Brahmsphantasie, Klinger divided the work into 3 sections: 1) a set of five songs, 2) images related to the Prometheus story, and 3) a piano-vocal score for Brahms’ Schicksalslied with interspersed images.

Brahmsphantasie Cover

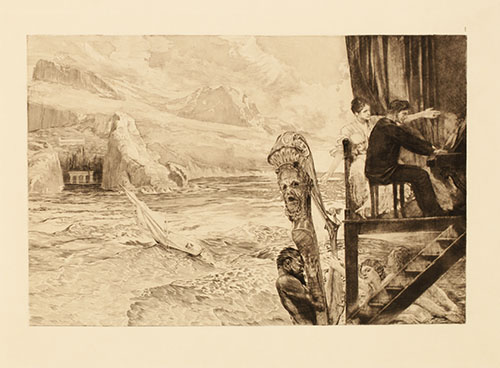

The book opens, however, with a dramatic interior/exterior scene. Inside, Max Klinger is at the piano in a room that opens out onto a roaring sea. A woman in white seated next to him, too far back to be the page turner, gestures at the music and at the world outside. Behind Klinger, at the edge of the sea are a triton and some nereids, clutching a very shocked harp. A sailboat makes its way to the Isle of the Dead (see Böcklin’s painting). Other paintings by Böcklin are also referenced in this image.

Klinger: Brahmsphantasie: Accord

Böcklin: Isle of the Dead

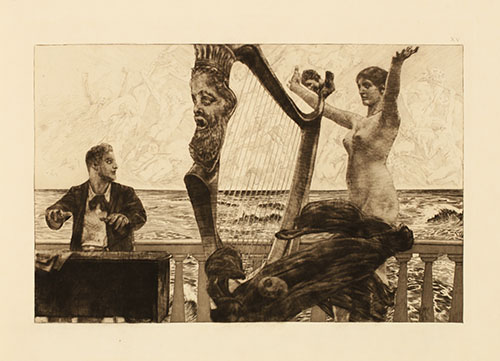

This painting, Accord (Harmony), faces a scene with many of the same characters, but now the nereid is at the same level as Klinger, i.e., in the salon, with the harp the curtains are thrown open and the raging sea seems to enter the room.

Brahmsphantasie: Evocation

The first work set is the song ‘Alte Liebe’ (Old Love), to a poem by Karl August Candidus. Spring has come and catches the poet unawares, bringing back memories and images of his old dream of love. In his 4 pages of illustration, Klinger is stretched out on the roof, one slipper discarded, going through his old love letters, accompanied by a dispirited Cupid. The piano is in the parlor and the city, seeming Florence, stretches behind him as he lies in shadow.

Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Alte Liebe, page 1

On the last page, birds emerge from the music and fly around the city, painting the first line of the poem: ‘Dark swallows are returning….’

Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Alte Liebe, page 4.

Brahms: 5 Gesänge, Op. 72: No. 1. Alte Liebe (Grace Bumbry, mezzo-soprano; Beaumont Glass, piano)

The next song is ‘Sehnsucht’ (Yearning) with a text by Josef Wenzig. The poem mourns that his love is invisible behind natural barriers and commands the rocks to shatter and the valleys be leveled so that he might just glimpse her.

Brahms: 5 Songs, Op. 49: No. 3. Sehnsucht (Peter Anders, tenor; Michael Raucheisen, piano)

‘Am Sonntag Morgen’ (On Sunday morning) to a poem by Paul Heyse, the poet sees his lover go out, dressed ‘so gracefully,’ but people come and complain to him about her behavior. Publicly, he just laughs at their stories but at home, he weeps and wrings his hands raw.

Brahms: 5 Lieder, Op. 49: No. 1. Am Sonntag Morgen (Bernarda Fink, mezzo-soprano; Roger Vignoles, piano)

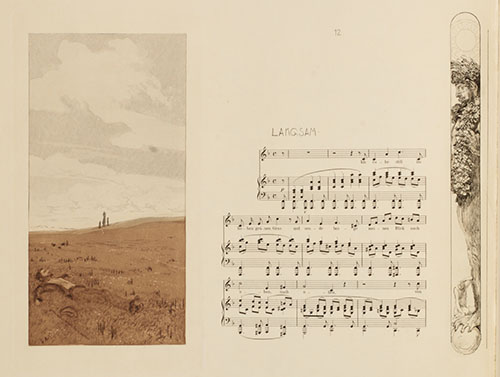

Another song with a nature setting, ‘Feldeinsamkeit’ (Solitude in a Field) depicts the poet sitting in a field, listening to the crickets, watching the clouds drift by in a blue sky, and feels as though he’s ‘long dead’ and blissfully drifting through space. Klinger shows the poet stretched on the field, stick and hat at his side, looking into the faraway sky.

Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Feldeinsamkeit, p. 1

Brahms: 6 Lieder, Op. 86: No. 2. Feldeinsamkeit (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone ; Gerald Moore, piano)

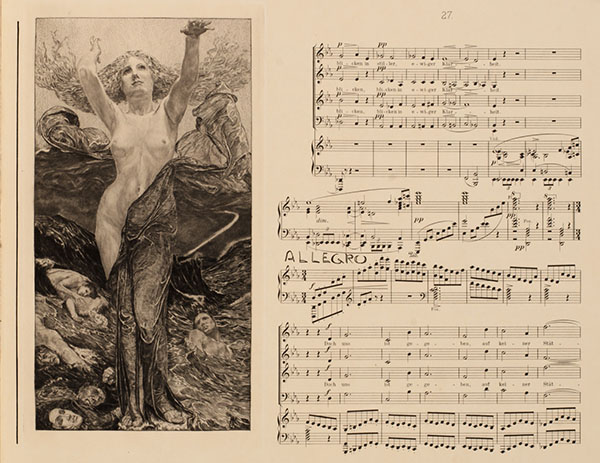

Next is the poem ‘Hyperions Schicksalslied’ (Hyperion’s Song of Destiny) by Friedrich Hölderlin. The text, ‘You wander above in the light’ addresses the divine beings that surround us invisibly, whereas the poor humans vanish and fall, blind to the beauties around us that protect us. Hölderlin meant to show the contrast between the happy life of the gods and the troubled fate of man. First Klinger writes out the poem and then starts with a piano-vocal score for the work.

On p. 6 of the score, a woman throws off her cloak, while around her in the sea are people who have fallen and washed away.

Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Schicksalslied, p. 6

Brahms: Schicksalslied, Op. 54 (San Francisco Symphony Chorus; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Herbert Blomstedt, cond.)

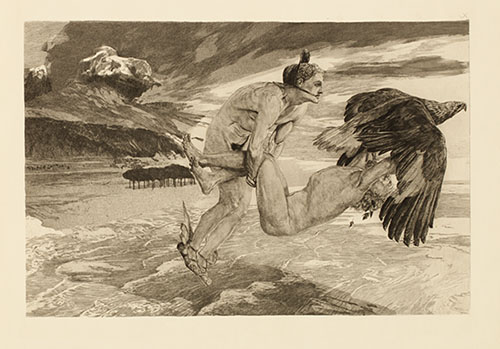

A six-page pictorial interlude follows, telling the story of Prometheus, bringer of fire to humans.

Klinger: Brahmsphantasie: Prometheus, p. 3

For this theft from Zeus, Prometheus was chained to a mountain top to be tormented by Zeus’ eagle until he was freed by Hercules. Here, Klinger shows the eagle and Mercury, carrying off Prometheus to his punishment

Klinger: Brahmsphantasie: Prometheus, p. 5

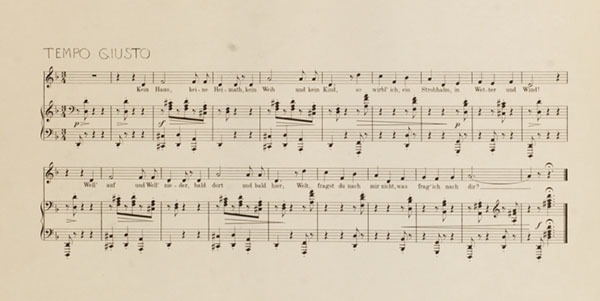

The book closes with a return to Brahms with ‘Kein Haus, keine Heimat’ (No house, no homeland), setting a text by Friedrich Halm. It’s a song of travel – with no house or homeland, no wife or child, the poet can go anywhere and the world can ask nothing of him. Accordingly, there’s no image by Klinger on this page. Scholars hold that Klinger meant to do an illustration for this page and so the book is incomplete, but other say that Klinger’s statement that one work was left ‘standing alone’ shows that the work is complete as it is.

Klinger / Brahms: Brahmsphantasie: Kein Haus, keine Heimat

Brahms: 5 Lieder, Op. 94: No. 5. Kein Haus, keine Heimat (Martin Hensel, baritone; Hedayet Djeddikar, piano)

At a time when the idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), first used in terms of music by Richard Wagner in 1849, was the idea of the day, Klinger’s combination of music and graphic arts was a unique and ground-breaking creation. The selection of the music was his own. and his artist’s repertoire for his images included lithography, etching, engraving, mezzotint, and aquatint. Although a ‘monumental’ work, it is also clearly intended for looking at in quiet contemplation. Klinger had five copies of the deluxe first edition printed and only 150 copies of the second edition. This was not intended for the masses.

The book was intended to be presented to Brahms on his sixtieth birthday (7 May 1893), but the artist missed the deadline. A final version was given to Brahms on New Year’s Day 1894. Brahms’ reaction caught the idea that Klinger was trying to convey:

Brahms to Klinger: Perhaps it has not occurred to you to imagine what I must feel when looking at your images. … Beholding them, it is as if the music resounds farther into the infinite and everything expresses what I wanted to say more clearly than would be possible in music…

Click here for more details on Brahmsphantasie.