The art of mourning in the 16th century was at its highest in the musical genre known as the Déploration. Following the model of French poets, where a déploration was a poem noting the death of an individual and those who knew him or knew of him were called to mourn, the musical déploration set those texts to song.

We can trace the movement of the déploration from poetry to music through the activities around the death of the French composer Ockeghem (d. 1497). At his death, the poet Crétin wrote a poem of over 400 lines in his memory. In the poem, Crétin asked all who ‘held Ockeghem dear’ to honour him, suggesting that they set particular texts for him. He particularly charged the composers Alexander Agricola (ca 1446–1506), Johannes Verbonnet (aka Ghiselin) (fl. 1455–1511), Johannes Prioris (ca 1460–ca 1514), Josquin des Prez (ca 1450–1521), Gaspar van Weerbeke (ca 1445–after 1516), Jacques Brunel (d. 1564), and Loyset Compère (ca 1445–1518) to set the text Ne recorderis ‘to lament your master and father’. By calling on the cream of the Netherlands composers to honour Ockeghem, Crétin created an opportunity for them to demonstrate their art.

Ockeghem and singers of the royal chapel, 1523 (Ms. fr.1537 fol. 58v der Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

In this posthumous miniature of 1523, Ockeghem (front row, with hooded cloak) leads the singers of the French court where he served for nearly 50 years.

As far as we can discover, no composer set Ne recorderis to music, but in his poem to the composers, Crétin also called out the Burgundian poet Jean Molinet, asking him why he hadn’t written anything commemorating the death of Ockeghem. Molinet rose to the occasion and wrote two poems, one in Latin and one in French, and the latter was chosen by Josquin Desprez for his déploration on Ockeghem’s death.

Leonardo da Vinci: Portrait of a Musician, thought to be Josquin, unfinished, ca 1483–87 (Pinacoteca Ambrosiana)

Molinet’s poems, Nymphes de bois, calls on the mythological creatures of the world to change their songs to cries and lamentations because of the death of Ockeghem.

| Nymphes des bois | Nymphes of the woods |

| Nymphes des bois, déesses des fontaines, | Wood-nymphs, goddesses of the fountains, |

| Chantres experts de toutes nations, | skilled singers of every nation, |

| Changez voz voix tant clères et haultaines | change your voices, strong, clear and high, |

| En cris trenchans et lamentations. | to cries and lamentation |

| Car Atropos, très terrible satrape, | because Atropos, terrible goddess of fate, |

| A vostre Ockeghem attrapé en sa trappe. | has caught your Ockeghem in her trap, |

| Vrai trésorier de musique et chief d’œuvre, | the true treasurer of music and master, |

| Doct, élégant de corps et non point trappe. | learned, elegant of form and figure. |

| Grant dommage est que la terre le couvre. | It is the greatest pity that the earth covers him. |

| Acoustrez vous d’habits de deuil | Put on clothes of mourning, |

| Josquin, Pierson, Brumel, Compère, | Josquin Desprez, Brumel, Pierre de la Rue, Compère, |

| Et plourez grosses larmes d’œul : | and weep great tears from your eyes, |

| Perdu avez vostre bon père. | for you have lost your good father. |

| Requisat in pace. Amen. | |

| tenor | |

| Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, | |

| and let perpetual light shine upon them. |

Like Crétin, Molinet calls on the finest composers of his generation to mourn the loss of Ockeghem: Josquin, Antoine Brumel (ca 1460–1513), Pierre de la Rue (ca 1452–1518), and Loyset Compère (ca 1445–1518) and it was Josquin who rose to his call. The Requisat in pace text from the mass for the dead, was added by Josquin in the middle, tenor, voice, making the ‘poetic lamentation and the ritual melody…intertwined, inseparable’.

Josquin’s setting of Nymphes des bois was for 5 voices: four singing the poem and the fifth voice singing the Requiem from the Mass for the Dead.

Josquin des Prez: Nymphes des bois (Netherlands Chamber Choir; Paul van Nevel, cond.)

The work became one of Josquin’s most famous pieces, circulating widely in Europe. It is assumed it was written in 1497 shortly after Ockeghem’s death and was still being published 50 years later. It appears in the Medici Codex, a wedding present from Pope Leo X (1475–1521) to his nephew Lorenzo II de’ Medici on his marriage to Madeleine de la Tour d’Auvergne in 1518.

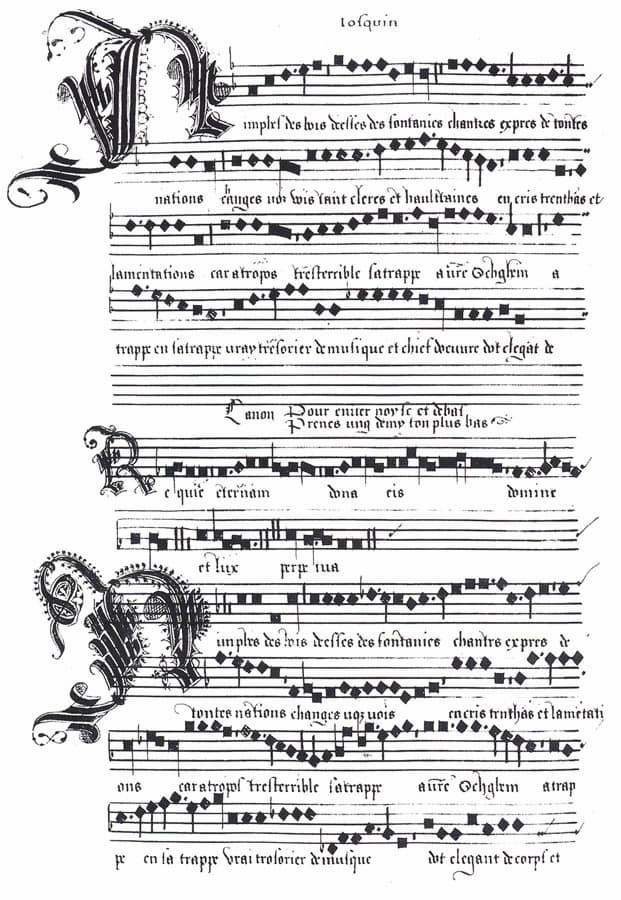

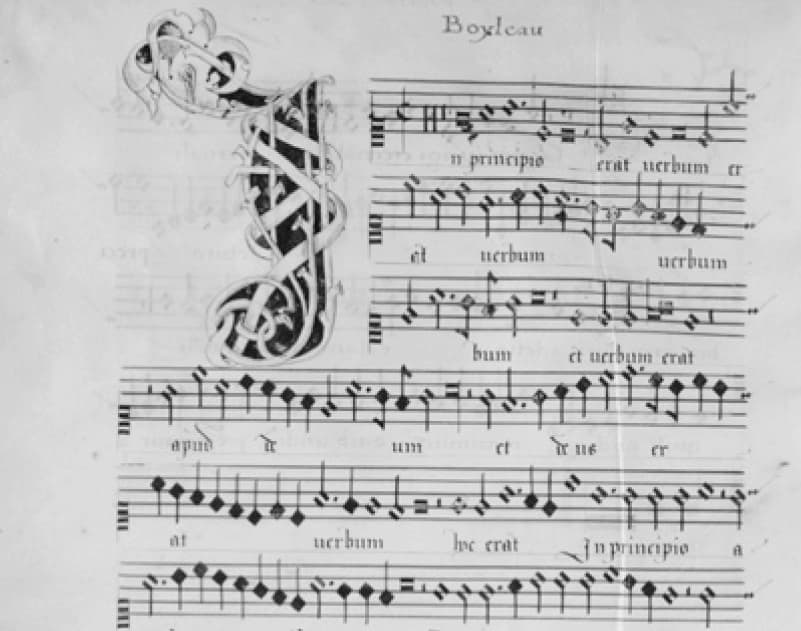

When we look at the music in the Medici Codex, we can see one aspect that shows the mourning quality of the work: all the music is black. This is called Augenmusik, i.e., music for the eye – it doesn’t affect the performance and the audience is unaware of this; it is only for the eye of the reader, i.e., the singer.

Medici Codex: Nymphe des bois

We can compare this with another work in the same collection: Boyleau’s In principio era verbum, where we can see what would have been the regular ‘white’ notation.

Medici Codex: In principio erat Verbum

What’s interesting about déplorations is that, since they are pieces in honour of a dead musician, they use very old-fashioned techniques, as the older musician would have used. Augenmusik was one aspect, the use of Phrygian mode (as in Nymphes des bois and other déplorations), and a low tessitura. In the music, counterpoint techniques such as canon is used (as in Jean Mouton’s déploration for Antoine de Févin in 1512 and in Pierre Certon’s for Claudin de Sermisy in 1562). The younger composer might also emulate nuances of the older composer’s style: Josquin’s opening of Nymphes des bois has a musical citation of Ockeghem’s greatest mass, the Missa cuisuis toni. Another déploration quotes a dead composer’s own mass for the dead. Josquin’s music also mimics Ockeghem’s older contrapuntal style.

Jean Mouton: Qui ne regrettroit le gentil Févin (Sesinta ; Mark Chambers, cond.)

Pierre Certon: Déploration sur la mort de Claudin de Sermizy (Vox Cantoris; Jean-Christophe Candau, cond.)

The other aspect of a déploration poem was its placement of the departed figure in an eternal dynasty. Crétin’s poem cites both pagan (Orpheus) and sacred (King David) musicians as part of the long line that culminated in Ockeghem. Molinet’s poem cries that Ockeghem’s death was an action by Atropos, the member of the Three Fates who controls the length of life. By calling contemporary musicians to join in a timeless line of musicians, the poets called for the music of memorials that would become the music of time immemorial.

Atropos cutting the thread of life

Composers still write memorials for dead musicians, we have works such as Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten, Alfred Schnittke’s Prelude in Memoriam Dmitry Shostakovich, Pierre Boulez’ Rituel in memoriam Bruno Maderna, but these are largely instrumental works and not driven by the leading poets of the day. We’ve lost the universal idea of mourning across the arts for a respected and revered composer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter