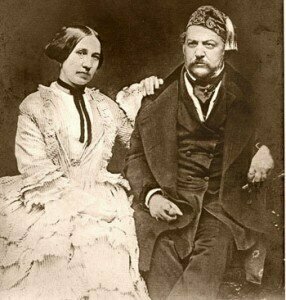

Mikhail Glinka and Maria Petrovna

Her name was Maria Petrovna Ivanova, and she was his sister’s brother-in-law’s wife’s sister. During a brief and intense period of courtship the couple frequented the living room of Vasily Zhukovsky, one of the best-known Russian poets. Zhukovsky held musical and literary salons, and assembled the crème-de-la-crème of the Russian literary elite, including Pushkin, Gogol, and Pletnev. When Glinka confessed that he wanted to write an opera, Zhukovsky offered him the story of “Ivan Susanin.” Set in 1612, it told the legend of the Russian peasant and hero Ivan Susanin who sacrificed his life for the Tsar by leading astray a group of marauding Poles who were hunting to kill him. Glinka was fire and flame, and happily agreed to set it to music. In his artistic enthusiasm he plainly overlooked that Maria Ivanova had no interest in music whatsoever!

A Life for the Tsar, written by Mikhail Glinka (Moscow, 1908)

However, things were not going all well at home. Already, during the composition of his opera, Maria Petrovna complained that he “was wasting too much money on music paper.” In retaliation, she started to spend money on frilly dresses and beauty products, and Glinka remembers his wife flirting with every man in sight. His mother-in-law’s constant nagging exacerbated these domestic battles, and Maria once commented on Pushkin’s death caused by a duel he fought to clear the name of his wife. “She uttered the opinion that all artists inevitably come to a bad end,” to which Glinka replied that he “would never risk his life to defend her good name, because there was no good name left to defend.”

In the autumn of 1839 Glinka was definitively told by several of his friends about his wife’s infidelity. Deeply shamed, he left his home of many years and never returned. He immediately wrote a letter to Maria telling her that he wanted a divorce, and that he would never change his mind. His friends urged him to reconsider, but a month later he collected all his personal belongings and his piano and never talked to her again. He unhappily told a friend “marriage is like counterpoint, nothing but opposition and contrary motion.”

Mikhail Glinka: A Life for the Tsar, Act 1 “Trio”