Edvard Grieg met Hans Christian Andersen in Copenhagen in 1864, when the writer and poet already enjoyed considerable fame in many parts of Europe for his stories, novels, and poetry. The two artists enjoyed a close kinship as both were regarded as innocent and almost childlike figures from Scandinavia.

Scholars quickly dispelled this popular misconception: “Andersen’s fairy tales were designed to be read on two levels: by children, who could simply enjoy the stories, and by adults who appreciated the deeper philosophy behind them.

Edvard Grieg: “My Little Bird” (Monica Groop, mezzo-soprano; Roger Vignoles, piano)

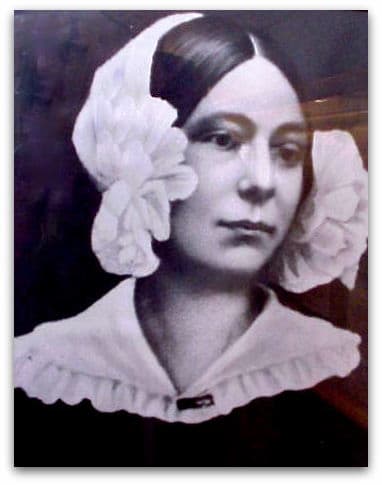

Hans Christian and Riborg

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen wrote eight short love poems entitled “Melodies of the Heart” in 1830, the result of his love for Riborg Voigt. Andersen was 25 years old, and his fellow student Christian Voigt, the son of a royal agent, shipowner, and merchant Lauritz Petter Voigt, invited the poet to his parents’ house. There, he met his sister Riborg Voigt, who very much liked his poems. Riborg and Hans Christian spent the next three days together with other young people from the town’s bourgeoisie.

When he met her, she was unofficially engaged to someone else, and although obviously attracted to Andersen, she married her fiancé six months later. A scholar writes, “Anderson tried to comfort himself with the idea that Riborg had really loved him and married only out of duty, and during the next few months, he wrote a substantial number of rather melancholy poems.”

Even after her marriage to another man, Andersen could not stop loving her. To be sure, Andersen never got over his love for Voigt, as he carried a letter from her in a pouch that he wore around his neck until he died at the age of 70.

Edvard Grieg: “Tears” (Monica Groop, mezzo-soprano; Roger Vignoles, piano)

Edvard and Nina

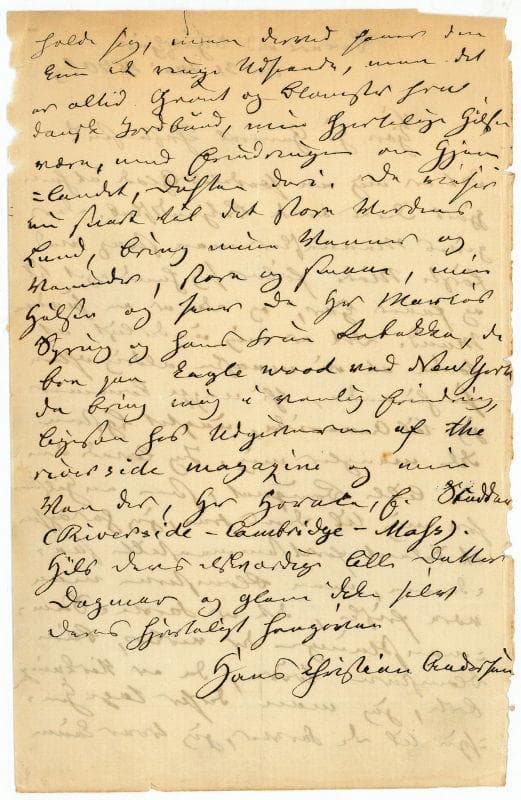

Riborg Voigt

Grieg set four poems from the “Melodies of the Heart” to music in 1864-5, around the time he met his cousin Nina Hagerup. Her mother, an actress of Danish origin, was the sister of Grieg’s mother. They had known each other as children, but sparks started to fly when they met again.

Around Christmas time in 1864, Grieg confessed his love, but both families rejected the engagement. Nina’s mother wrote, “he is nothing and he has nothing and he writes music that nobody wants to hear.” And Nina’s voice teacher, Carl Helsted, had nothing nice to say about Grieg’s music. Grieg’s parents were not overjoyed either and did not give permission for the engagement to be made public until July 1865.

In the event, Nina Hagerup and Edvard Grieg married in Copenhagen on 11 June 1867, in the absence of both sets of parents. Initially, Edvard earned income from giving piano lessons and Nina worked as a singing teacher. Nina was always highly supportive of Edvard’s work, and she became his musical partner, artistic advisor and assistant. In turn, Edvard regarded her as the best interpreter of his music, and according to a diary entry from 1905, even as the “only true interpreter” of his songs.

Edvard Grieg: Romances, Op. 15 “Love” (Jakob Zethner, bass; Kristian Giver, piano)

Melodies of the Heart

Andersen’s letter

Andersen’s poetry does make some brief allusions to mythology and history, but overall, the poems are pictures of homely scenes and simple faith. The language is rather uncomplicated, and the unsophisticated rhymes and rhythm make them ideal for musical settings.

In his musical settings, Grieg began to show signs of a maturing composer. They are the earliest examples of Grieg’s most distinctive and typical song-writing. Succeeding for the first time in finding a truly personal form or expression, these settings sound wonderful, fresh, and original. Grieg presented his “Melodies of the Heart” in secret to Nina as an engagement present.

Edvard Grieg: Melodies of the Heart, “Two Brown Eyes” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Two sparkling brown eyes I chanc’d to see,

they held my world and my destiny.

A peace so child-like in them did lie;

I’ll never forget them until I die.

The first song “Two Brown Eyes” has been described as one of the best of the set. It features a lively melody while the principal accompaniment figure has impudent charm. The setting is primarily diatonic, although Grieg frequently shifts between the major and minor modes. The accompaniment itself is independent and there is little chromatic writing.

Edvard Grieg: Melodies of the Heart, “The Poet’s Heart” (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Hartmut Höll, piano)

You understand not the eternal beating of the waves

Nor the spirit that dwells in the sound of the notes

Nor the feeling deep in the scent of the flowers,

The flame of the sun against storm and air

The longing and lust of the twittering birds

And yet you believe that you can grasp a poet’s breast?

For it swells more than the beating waves,

And is the source of every song.

The flower grows there, its scent everlasting

And there is fire with no cooling air.

Spirits struggle there, longingly, lustfully,

Fighting with death, deep in his breast.

Nina Grieg

The sentimental idea expressed in “A Poet’s Heart” ponders the question “if we cannot understand the wonders of nature, then how can we hope to understand the poet?” Grieg’s setting, according to scholars, “looks back to his Leipzig days, although the vocal phrases here are longer and freer.”

We get a sense of the turbulent thoughts behind the verse by listening to the rapid accompaniment. The harmony is basically straightforward but infuses passages of more complexity. Interestingly, Grieg features a dissonant ending in the postlude.

Edvard Grieg: Melodies of the Heart, “I Love you” (Bodil Arnesen, soprano; Erling Ragnar Eriksen, piano)

Thou art my joy, the radiance of my being,

oh my beloved, thou my ecstasy!

I cherish thee, my every passion freeing,

I love but thee now and eternally!

The third song of the group became, in numerous translations, the most celebrated of Grieg’s early songs. In fact, it has been described as “one of the Romantic period’s most treasured love songs.” It has a freshness and innocence that belies the fact that this song only features a single stanza. A good many translations and additions have added more lines or repeated the single stanza.

The musical structure has been described as “varied strophic, two stanzas of unequal length, the first parts of which are similar, while the last part of the second stanza is subtly varied and extended.” The tenderness and yearning of the melody and words are underlined by subtle chromatic gestures.

My mind is like the Mount Steep

That towers above the skies;

My heart is a sea so deep

Where wave beats against wave.

And the mountain bears up your image

High against the blue sky.

But you dwell in my heart

Where the deep waves break.

Edvard and Nina Grieg

The concluding song is set in a through-composed form, with the accompaniment sustaining the feeling of unrest in the poem. The angular vocal line portrays the mighty mountains towering into the sky in the beginning. The last line of the stanza is repeated in shorter note values, ending the song with a feeling of urgency.

Grieg could not find anyone to publish his “Melodies of the Heart,” and the set was first printed in Copenhagen in 1865 at the composer’s expense. A newspaper review described the songs as having “tuneful melodies and lively accompaniment, which, however, are not free from sometimes having too sudden changes of key, which seems to imitate the great model Schumann.” In the event, it was Andersen’s poetry rather than his other writing that greatly appealed to Grieg during this happy period in his life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Edvard Grieg: Melodies of the Heart, “My Mind is Like the Mountain Steep” (Per Vollestad, baritone; Sigmund Hjelset, piano)