Great Wall of China

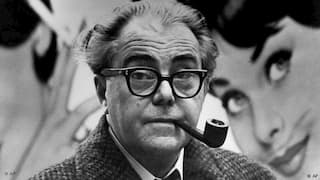

Only months after the horrendous atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Swiss playwright and novelist Max Frisch (1911-91) penned his theatrical play “The Chinese Wall.” It is in equal parts tragedy, comedy, history and satire that address the possibility of global extinction in the nuclear age.

Max Frisch

Rejecting all manner of authoritarian rule, the “Chinese wall,” essentially a national obsession for almost two thousand years, comes to signify the futility of building barriers to keep influences and ideas at bay. The play takes place in the Emperor’s court in Nanking, but Frisch includes a number of historical and literary figures, including Cleopatra, Brutus, Pontius Pilate, Romeo and Juliet, Columbus, Philip II of Spain, Don Juan, and Napoleon. Frisch’s fundamental message appears to be that “it is impossible to solve the problems of the 20th century by using methods that became obsolete in the third century AD.”

Einar Englund: The Great Wall of China Suite (Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra; Eri Klas, cond.)

Einar Englund, 1957

Originally, Frisch’s surrealist play included incidental music composed by Einar Englund (1916-1999). Described as a composer of great versatility, Englund was a representative of the “Finnish lost generation,” young men sacrificing their youth in the war. He served in the Finnish army during its conflict with the Soviet Union, and survived as he later recalled “by a sheer miracle.” Sadly, a wound to his right hand sustained in this conflict prevented him from attaining a full career as a pianist, and he focused his energies on composition. Englund won a scholarship to study with Aaron Copland in 1949, with Copland declaring, “Well, there’s nothing I can teach you!” His incidental music for “The Great Wall of China” was also composed in 1949, originally for a theatre band of seven. He later arranged the music for full orchestra, and its eight movement mingle the musical influences of Prokofiev with popular musical styles, including a “Tango,” “Rumba,” and a “Jazz-Intermezzo.” The music, according to the composer, does not contribute to the satire of the theatrical play, but rather suggests, “that no wall is strong enough to keep out ideas and influences.”