Louis Moreau Gottschalk

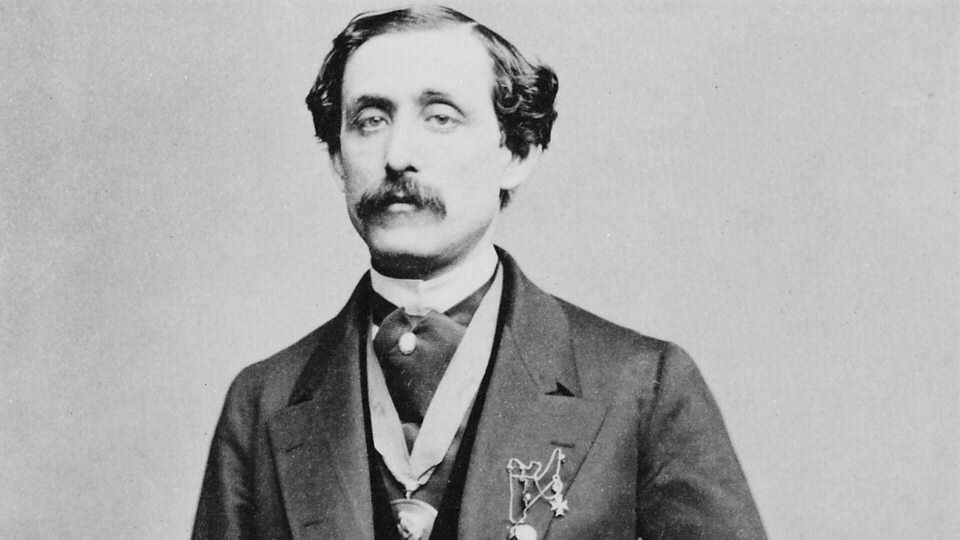

The teenage American sensation Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) played his name into the hearts of Parisian society. Paris was full with youthful geniuses, but one from America attracted special attention. His earliest music published in France in his name tellingly featured the accompanying phrase “de la Louisiane.” And a critic in La France Musicale of 1848 writes, “We have discovered this Creole composer, an American composer, bon Dieu! His music is wild, languishing, indescribable and has no resemblance to any other European music.” It’s hardly surprising that Gottschalk roused the curiosity of an entire nation, and he acquired a notorious reputation for his sexual exploits. A 1850 publication reported that “A young, pretty and robust Genovese girl waited for Gottschalk at the coming out of the concert, where the pianist had been covered with flowers, and enveloping him all at once in a large cloak took him in her arms and carried him off, which the frail and delicate nature of her victim permitted her to do easily, to the general consternation. We do not know if this be true; we tell it as it was told.”

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Le Mancenillier, Op. 11

Ada Clare

While we can easily dismiss the above anecdote as an invention of the gossip press, some reports were more accurate, not to mention more painful. During his tenure with Queen Isabella II of Spain, Gottschalk was romantically linked with the queen’s sister Doña Luisa, and the Countess de Montijo, who was soon to become the wife of Napoleon III.

News suddenly reached Paris that Gottschalk had injured his finger and needed to take a three-month sabbatical from playing. It’s not unusual for pianists to develop hand or finger problems over the course of their careers, but Gottschalk’s injure had nothing to do with the piano. In fact, it had been a vicious attack. When he entered his carriage, somebody called out his name. Gottschalk stopped halfway up the carriage to see who was calling for him. When he turned around with his hand grasping the doorframe, somebody snuck up from behind and slammed the door on Gottschalk’s hand. For some time it had been assumed that the jealous court pianist instigated the attack, but we have since learned that it was the doings of a jealous lover.

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: La jota Aragonesa, Op. 14 (piano 4-hands)

Ada Clare, cousin of the distinguished Southern poet Paul Hamilton Hayne, made several unsuccessful attempts to become a tragic actress. However, as a writer Clare was a central part of the Bohemian lifestyle in New York, and her weekly columns discussed a range of topics, everything from women’s rights to the state of the American theatre. The poet and essayist Walt Whitman described her “as representing the ideal of the modern woman: talented intelligent, and emancipated. Slender and elegant in black from head to foot; pure white complexion, pale chiseled features, perfect profile, abundant fair hair; abstracted look, and rather rapid, purposeful step.” Clare also had a widely publicized liaison with Louis Moreau Gottschalk. The affair, so it was reported, resulted “in an illegitimate son whom Clare then brandished in the face of conventional mores.” As it turns out, however, Clare’s child was actually fathered by Gottschalk’s brother, as both men had steamy affairs with her. Be that as it may, when the affair between Ada and Louis Moreau had run its course, the pianist embarked on a curious West Indian interlude with Salvatore Patti and his fourteen-year old daughter Adelina.

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Souvenir de Porto Rico, Op. 31

Adelina Patti

Gottschalk’s tour to California in 1865 was going well, until a report surfaced in the local newspaper that he and an acquaintance allegedly met with two un-chaperoned schoolgirls on a dark secluded road. Gottschalk was not mentioned by name, but it was clear that the description of “a strolling pianist,” fit his profile. The affair became a full-blown scandal, and there were calls for him to be tarred and feathered. We really don’t know what happened that evening, but Gottschalk wrote down his version in a letter from 15 September 1865. His friend and colleague Legay had received an anonymous letter from a secret admirer who, it turned out, was enrolled in the Oakland Female Seminary and was twenty years old. “In the letter she proposed a rendezvous that evening on a deserted road, and asked Legay to bring a friend. Gottschalk initially declined, but eventually went along.” Gottschalk quickly realized that he was “nothing but a substitute for Sbriglia the tenor, and unpleasant words were exchanges.” Gottschalk and Legay left the girls on the road but they were later caught attempting to sneak back into the Seminary. Initially, Gottschalk was not concerned over the nocturnal meeting and performed the next evening. When the story broke in the local newspapers, however, Gottschalk hurriedly and in disguise boarded the steamship Colorado bound for Panama.