120 years ago, on 22 February 1903, Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) died in an insane asylum after trying to drown himself in October 1898. He had last appeared in concert on February 1897, but the impending paralysis of tertiary syphilis was accompanied by outbursts of violent temper and restlessness. As a biographer writes, “by 19 September 1897 it was evident to his distressed friends that he had lost his mind… The delusional Wolf insisted that he was the new director of the opera and had dismissed Mahler from his post.”

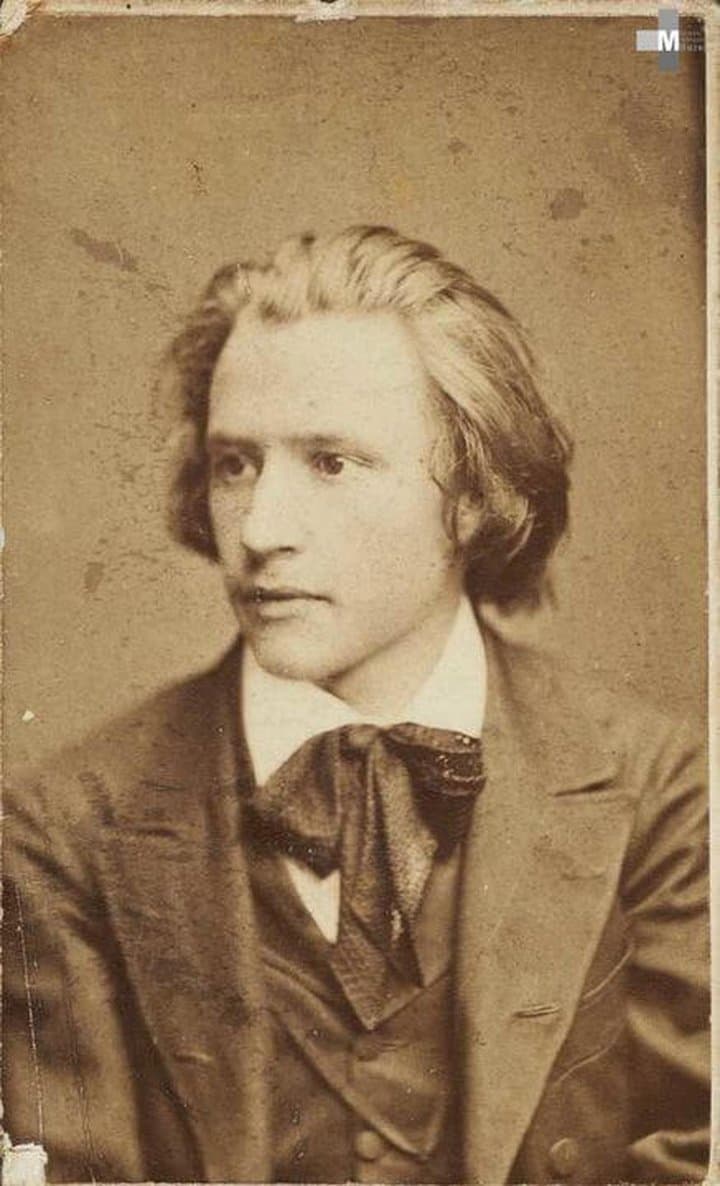

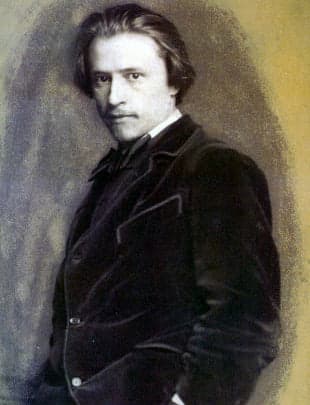

Hugo Wolf

Wolf was feverishly working on an unfinished opera, Manuel Venegas in 1897, and he left sixty pages of unfinished score before losing his mind completely. He was taken away in a straightjacket to Dr. Wilhelm Svetlin’s asylum for the insane, “from which he wrote letters of accusation against the friends who had betrayed him.”

Hugo Wolf: Italian Serenade

Wolf’s Painful Last Days

Hugo Wolf: Letters to Melanie Köchert

His condition improved for a few months in 1898, which allowed him to travel, but his madness resumed and he tried to drown himself in Lake Traun. Wolf returned at his own request to the asylum, and he was cared for by the Hugo-Wolf-Verein, with Melanie Köchert visiting him three times a week. Melanie was the wife of a prominent Viennese jeweler with whom Wolf shared a lifelong sexual, emotional, spiritual, and artistic bond. After the summer of 1899, Wolf was no longer able to engage with music or the world, and he “endured the long agony of his insanity until his death.” Wolf is buried in the Central Cemetery in Vienna, near the graves of Schubert and Beethoven. Melanie was increasingly plagued by her unfaithfulness to her husband, and full of self-reproach repeatedly exclaimed “I have been a bad wife.” On 21 March 1906, overcome by melancholy and guilt, she threw herself from the 4th-floor window of her Vienna home to her death.

Hugo Wolf: Michelangelo Lieder

“I got the impression that I was not understood”

Hugo Wolf, 1902

Wolf’s creativity was informed by a concentrated expressive intensity that saw several bursts of extraordinary productivity. Uncompromising, and known for the intensity and expressive strengths of his convictions, he was commonly known as “Wild Wolf” and he made powerful enemies. Not surprisingly, he frequently felt misunderstood as a composer. “The principal pain of my art,” he writes, “is rigorous, bitter, inexorable truth—to the point of cruelty.” As he wrote to Melanie Köchert, “On the whole, I got the impression that I was not understood, that critics busied themselves too much with musical matters and thereby forgot what is new and original in my musico-poetic conception.” As a scholar writes, “Wolf’s songs must not be judged as music, but only in relation to the degree to which they succeed in recreating the poem’s words, mood and meaning. The music makes no sense apart from the text.”

Hugo Wolf: Liederstrauß, “Sie haben heut’Abend Gesellschaft” (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Hartmut Höll, piano)

Childhood Years and Music Education

Birth house of Hugo Wolf

Wolf was born on 13 March 1860 in the small town of Windischgraz in the Duchy of Styria, then part of the Austrian Empire. His mother Katharina was a shrewd, practical, and energetic woman, and four years older than her husband Philipp Wolf. He had inherited a leather manufacturing business established by his grandfather, and he had considerable musical gifts. He taught himself to play the piano, violin, flute, harp, and guitar. As a biographer writes, “both his musical gifts and moody temperament were passed to his fourth child Hugo.” Young Hugo showed exceptional abilities in music at an early age, and he received piano and violin lessons from his father at the age of four. Entirely focused on music, Hugo was expelled from a number of secondary schools, dismissed for “being wholly inadequate,” and for “breach of discipline.” He pleaded with his father to let him attend the Vienna Conservatory, and after some initial resistance, Hugo began his musical studies in Vienna in September 1875.

Hugo Wolf: Variations in G Major, Op. 2 (Ana-Marija Markovina, piano)

A Dedicated Wagnerian

Museum Hugo Wolf, in the composer’s Birth house

At the conservatory, Wolf made friends with Gustav Mahler and declared himself a “dedicated Wagnerian.” He spoke to Wagner on a couple of occasions, but his idol was unwilling to spend any time examining the compositions presented to him. Yet once again, Wolf was in conflict with authority and dismissed. “The conflict was aggravated by a fellow student who sent the director Josef Hellmesberger a death-threat signed ‘Hugo Wolf.” By March 1877, Wolf was on a train back to his home. He returned to Vienna eight months later and earned his own living as a music teacher. Wolf probably contracted syphilis in 1878, and he fell deeply in love with the society beauty Vally Franck. The affair lasted for three years, and when she left him just before his 21st birthday, he was devastated. A scholar writes, “The affair was a vital impulse of Wolf’s life as he turned to the compositions of more songs.”

Hugo Wolf: 6 Geistliche Lieder (North German Figural Choir; Jorg Straube, cond.)

Hugo Wolf at age 16

Wolf had a momentous interview with Brahms in 1879, but Brahms’ response was predictably blunt. Wolf later reports, “I once sent him a song and asked him to mark a cross wherever he thought it was faulty. Brahms returned it untouched, saying I don’t want to make a cemetery of your compositions.” It pushed Wolf to become a fanatical Wagnerite, “who even copied his master to the point of aping his vegetarianism.” Wagner’s death in February 1883 left Wolf in a despairing mood, as “in a world from which his idol had departed, leaving tremendous footsteps to follow, he received no guidance on how to do so.” Wolf made several pilgrimages to Bayreuth, and through Melanie Köchert’s intervention, he was appointed music critic at the Wiener Salonblatt. He certainly made more enemies than friends, yet he still sent his score for his symphonic poem Penthesilea to the Vienna Philharmonic in 1885. When the work was trialed a year later, the orchestra supposedly burst into derisive laughter at the end “and Wolf overheard disparaging remarks by the conductor Richter about people who dared to criticize the great Brahms.” Wolf swore revenge exclaiming, “They shall be roasted in hell’s brimstone and immersed in dragon’s poison—I have sworn it.”

Hugo Wolf: Penthesilea (Jena Philharmonic Orchestra; Simon Gaudenz, cond.)

Hugo Wolf as a Lieder Composer

The young Hugo Wolf

Wolf abandoned his activities as a critic in 1887 and began to compose with a newly found intensity. For nine years, punctuated by long silences, Wolf’s songs “display an idiosyncratic merger of traditional and novel elements.” His taste in poetry had always been conservative, as he characterized contemporary poets as “bunglers.” It comes as no surprise that his favorite writer was the Biedermeier poet Eduard Mörike (1804-75). Wolf prided himself on his ability “to create different characterizations in music,” and he found fertile grounds in the protean variety of Mörike’s poetry. We find poems about love, nature, role poems about genre characters, religious subjects, comedy, erotic poems, songs of fantastic-supernatural creatures, ballads, and more. As Susan Youens writes, “Moreover, Mörike had not been appropriated by Wolf’s great songwriting predecessors in the way that Schumann, for example, is forever linked with Heine. The psychological depths of this verse, and its avoidance of overt subjectivity, were other attractions of a poet Wolf could claim as his own in a manner that liberated his creative imagination.”

Hugo Wolf: Mörike Lieder, “Wo find ich Trost”

Wolf was starting to be acknowledged in Vienna and further afield. In 1889, he set to work on his Spanisches Liederbuch, selecting 44 poems from an 1852 volume of translations by the poet Emanuel Geibel and Paul Heyse. Schumann and Brahms had previously set some poems, but Wolf “characteristically chose poems overlooked by previous composers.” And thanks to some influential friends, Wolf now had the attention of Schott, one of Germany’s foremost music publishers. For some critics, Wolf was now “a lieder composer of the first rank… since Schubert we have seen few equal to him.” However, in many of his letters, Wolf deeply worried about being merely a song composer, as prestige and acceptance of greatness were found in opera and symphonic music. “The flattering acknowledgement of me as a song composer,” he writes, “distresses me to my innermost soul.” In fact, Wolf thought of his Spanish songs as a kind of preparation for writing an opera.

Hugo Wolf: Spanisches Liederbuch, “Geistliche Lieder” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Olaf Bär, baritone; Geoffrey Parsons, piano)

Operas by Hugo Wolf

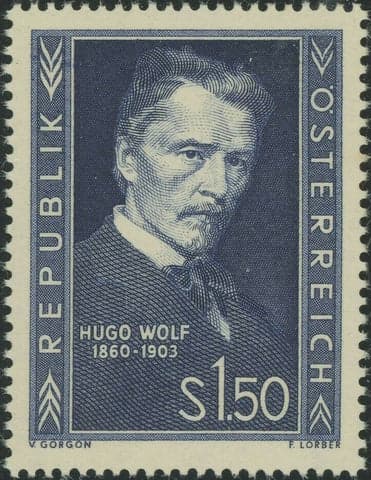

Hugo Wolf being featured on an Austrian postal stamp

Wolf’s operas, one finished, one unfinished are effectively a string of songs “many of them beautiful, powerful, psychologically acute in musical characterization, but not expansively conceived.” This comes as no surprise as Wolf’s musical thought emerged in terms of the piano and the solo voice. In the harmonic and tonal realms, he was a master of ambiguity created in numerous ways, such as his use of a dual focus on two tonal areas at once and his “frequent recourse to harmonic substitution of chords that act in place of those expected in conventional functional progressions.” Always psychologically probing, musically profound, and emotionally penetrating, Wolf had a genius for vivid and varied musical analogues to sights and sounds of the external world evoked in his chosen poems.” Wolf was not a melodist in the strict sense of the word, as “his strength resides in the invention of succinct characterizing piano motives and in a painfully sensitive treatment of the words.” His music makes audible a dimension of what remains unsaid, as “Music and language form a unity, not by virtue of the fact that the former repeats what the latter already says anyway, but because music listens to language and makes audible what is latent in it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hugo Wolf: Italienisches Liederbuch (excerpts)