Listening to a performance of Handel’s Messiah has long been an Easter tradition in many parts of the world. It is undoubtedly one of the composer’s most popular and enduring works, as it features three distinct parts: the Prophecy of the Messiah, the Passion and Redemption of Christ, and a hymn of Thanksgiving. As Christopher Hogwood writes, “the libretto presents a coherent progress from Prophecy, through Nativity, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension to the promise of Redemption. It thus encompasses all the major festivals of the Christian year, but Handel himself associated performances of his oratorio with Easter.”

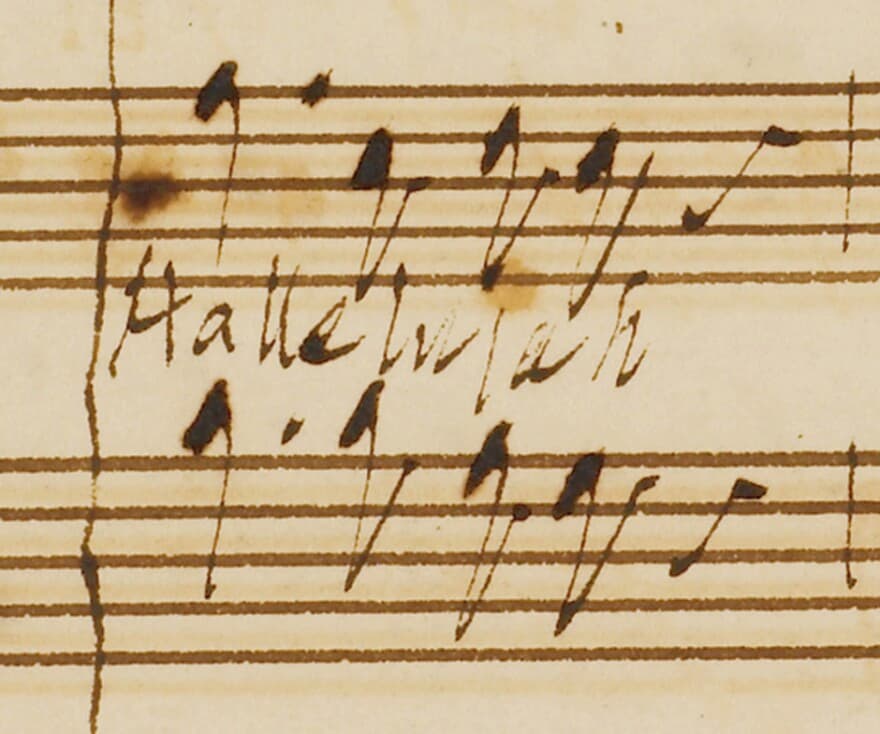

Handel’s Messiah “Hallelujah”

For a good many commentators, the most impressive part of Handel’s musical setting is found in his distinctive choral style. Handel frequently uses choruses in the oratorios where you would normally find an aria in an opera. The chorus comments or reflects on a situation, but the “emphasis is on communal rather than individual expression.” Just in time for the Easter holiday, let us take a closer listen to the choruses from Part II of Messiah, starting with Scene 1 titled “Christ’s Passion.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II: “Behold, the Lamb of God” (Oxford New College Choir; Academy of Ancient Music; Edward Higginbottom, cond.)

George Frideric Handel

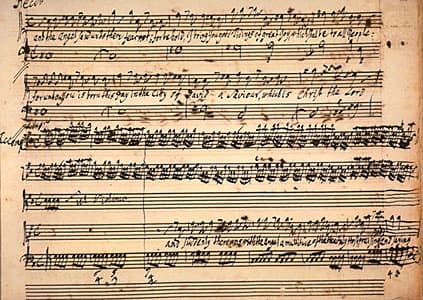

The first scene in Part II reflects the Passion, and according to the librettist, it “expresses Christ’s scourging and the agony on the cross.” This is the only part of the oratorio that opens with a chorus, and the entire section is essentially dominated by choral singing. The opening chorus “Behold the Lamb of God,” opens with a French overture in a minor key, “representing tragic presentiment.” After only a couple of instrumental measures, the altos proclaim, “Behold the Lamb of God,” and the other voices follow in quick imitation. The dotted melody briefly rises to the major mode on “that taketh away the sin of the world,” and once the words are stated in brief solid blocks of harmony, the music returns to the instrumental introduction. This brief and somber opening chorus immediately sets the stage for the suffering of Christ, but the brief major mode interjections provide the expected theological and musical glimmers of hope.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Surely He hath borne our Griefs” (St. Jacob’s Chamber Choir; Baroque; Gary Graden, cond.)

For Christopher Hogwood, “the choruses of Messiah are the keystones of its dramatic and musical structure.” For me, they also contain tremendous emotional highlights, as Handel’s music is rich with pictorial and affective musical symbolisms. Scholars consistently point to Handel’s psychological and theatrical skill, such as it is heard in the chorus sequence starting with “Surely, he hath borne our griefs.”

Surely He hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows!

He was wounded for our transgressions;

He was bruised for our iniquities;

the chastisement of our peace was upon Him.

The jagged dotted rhythms and dark minor key immediately recall the agonies of the crucifixion. The mood is one of desolation and continued from the previous aria. However, the protagonists are now being divided as Jesus is musically set against the crowd.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “And with his stripes are healed” (St. Jacob’s Chamber Choir; Baroque; Gary Graden, cond.)

Handel’s Messiah title page

Continuing in the same key, the chorus “And with his stripes are healed” offers a more intellectual approach, as “the fugue subjects of the strongest intervals are used in the most reiterative manner.” Hogwood here references the powerful ascending fourth in the countersubject, and there is a reason it sounds vaguely familiar. Mozart quotes the sequence of the opening five long notes in the Kyrie fugue of his Requiem. Handel makes frequent use of word painting techniques, as we can hear in the long melismas set to the word “healed.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “All we like sheep have gone astray” (St. Jacob’s Chamber Choir; Baroque; Gary Graden, cond.)

Set on a walking bass with irregular patterns and leaps, the chorus “All we like sheep have gone astray” only momentarily relaxes the tension. As a scholar writes, “In Handel’s famous chorus sin glories in its shame with almost alcoholic exhilaration. His lost sheep meander hopelessly through a wealth of intricate semi-quavers, stumbling over decorous roulades and falling into mazes of counterpoint that prove inextricable. A less dramatic composer than Handel would scarcely have rendered his solemn English text with such defiance, for the discrepancy between the self-accusing words and his vivacious music is patent to any listener emancipated from the lethargy of custom.” All our foolishness is brought home in the final devastating section marked “adagio,” with note values doubled.

All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have turned every one to his own way.

And the Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II “He trusted in God that he would deliver him” (Barock Vokal Mainz; Neumeyer Consort; Michael Hofstetter, cond.)

Christopher Hogwood © Anne-Katrin Purkiss

A brief accompanied recitative delivers the devastating assessment “All they that see Him laugh Him to scorn; they shoot out their lips, and shake their heads, saying:” The response is given by one of only two “turba” choruses in the whole work. A “turba chorus” is essentially a crowd scene that portrays the onlookers or people in the streets, “often with a mob-like mentality.” The chorus “He trusted in God that he would deliver him” spews musical venom as the crowd is furiously mocking Christ. Set as a strict fugue in C minor, Handel’s turba chorus “comes close to those in the crowd scenes of German Passion music.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Lift up your head” (Boston Baroque; Martin Pearlman, cond.)

The scenes of the death and resurrection of Christ are set in two tenor solo movements, while Scene 3 of Part II refers in a chorus to the ascension.

Lift up your heads, O ye gates; and be ye lift up,

ye everlasting doors; and the King of Glory shall come in.

Who is this King of Glory? The Lord strong and mighty,

the Lord mighty in battle. Lift up your heads,

O ye gates; and be ye lift up, ye everlasting doors;

and the King of Glory shall come in. Who is this King of Glory?

The Lord of Hosts, He is the King of Glory.

Although it is not specifically suggested in the score, this chorus was probably performed in the Venetian manner of dividing the singers into two sounding groups. That division is also suggested by the text which asks the question “Who is the King of Glory,” and the answer “He is the King of Glory.” The alto line supplies the bass of one chorus and the top of the other. The high voices (soprano I and II, alto) become the announcing group and the low voices (alto, tenor, bass) ask the question. As Hogwood writes, “The dotted rhythms are not particularly suitable for the enunciation of the words, but highly suitable to express the ideas of kingship.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Let all the angels of God worship him” (RIAS Chamber Chorus; Berlin Akademie für Alte Musik; Justin Doyle, cond.)

A short recitative “Unto which of the angels said He at any time: “Thou art My Son, this day have I begotten Thee?” quotes from the Epistle of the Hebrews, and the text asserts that the Messiah is the begotten Son of God. The festive chorus “Let all the angels of God worship him” sounds a fugue in augmentation and diminution designed to complement the previous homophonic chorus “Lift up your head.” Handel’s musical approach is much more relaxed and less dramatic, “as this release of tension is needed if the final ‘Hallelujah’ is to have the full effect that Handel intends.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “The Lord gave the Word” (La Capella Reial de Catalunya; Le Concert des Nations; Jordi Savall, cond.)

As we are nearing the end of Part II, the libretto connects the victory of Jesus with the sending out of preachers into the world. “Thus the Messiah blends the story of Easter into the story of Pentecost, just as Eastertide bridges Easter Sunday and Pentecost Sunday.” The brief chorus “The Lord gave the word; great was the company of the preachers” is scored in the bright key of B-flat Major, imparting a joyous atmosphere. Handel divides the chorus into two halves, with the upper and lower voices intertwining with the two lines of the psalms. “The long melismatic lines are lyrical and add colour to the music, with the voices splitting into four to create a glorious chord on the word ‘company.’” As has been observed, “this kind of word painting is subtle, but shows just how detail-oriented Handel was when constructing this epic work.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Their sound is gone out into all lands” (London Philharmonic Choir; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Adrian Boult, cond.)

The deliberate contrast in mood between the chorus “Their sound is gone out into all lands, and their wounds unto the ends of the world” to the preceding aria, prepares us for the drama ahead. In this short chorus the voices and orchestra often sound in unison, “with more contrapuntal lines sticking out and showing the development of the music.” Handel creates a rich texture laden with beautiful harmonies, and the word-painting of the scales going to “the ends of the earth” is ingeniously set against the fanfare figure of “Their sound is gone out.” This particular chorus was added after the premiere performance in Dublin.

“Let us break their bonds asunder, and cast away their yokes from us” is the second turba chorus in Part II. It is the continuation of the text of the previous interrupted aria, as the chorus once again represents a crowd scene. The aria asks the question “why do the nations so furiously rage together, and why do the people imagine a vain thing? The chorus interrupts the aria, and a constant entry of voices creates a rather chaotic opening. Handel introduces two characterful fugue subjects, which “increase the restlessness of the mood.” Characteristically, Handel brings the voices back together in unison passages, and fast successions of entries musically paint “breaking their bonds. The chorus concludes with a tight stretto, with all fugal entries sounding together.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Let us break their bonds asunder” (Daniela Dolci, organ/cond.; Musica Fiorita)

Handel’s memorial at Westminster

In effect, Handel has been building dramatic tension throughout the second Part of Messiah. He now arranges for the release of this accumulated energy in the most effective manner. The majestic and triumphant “Hallelujah Chorus” has become one of the most easily recognized works of classical music in today’s popular culture. It signifies any kind of jubilant celebration, however, in the context of Messiah, it is the specific celebration of Christ’s ultimate sovereignty over earthly kings and lords. An often-repeated story tells that a servant found Handel sobbing with emotion while writing the famous “Hallelujah” chorus. Apparently, the composer claimed, “I did think I did see all Heaven before me and the great God Himself.” Although such reports are not entirely trustworthy, they did help to foster an image that his particular work was divinely inspired. And we do know for certain that Mozart re-orchestrated the work in 1789, insisting that “any alterations to Handel’s score should not be interpreted as an effort to improve the music.” Not to be outdone, Beethoven famously proclaimed Handel to be the “greatest composer that ever lived.”

Scored in the bright key of D Major, the choir exuberantly chants “Hallelujah,” which surrounds and interacts with the monophonic declamation of the text proper. A reflective 4-part section seamlessly flows into a boisterous fugal exposition—also featuring monophonic interjections—and the chorus gloriously concludes with an elaborate restatement of praise. The final acclamation “King of Kings and Lord of Lords” is sung on just one note. Trumpets and timpani accentuate these outbursts further by adding weight and volume to the voices. The final few bars raise the Hallelujah higher and higher until its final full resolution on a dramatic ‘Hallelujah.’ Handel clearly understood the ways in which music and drama could work together. Lacking the visual operatic elements such as sets, costumes, props, and stage action, Handel had to draw even more keenly on his ability to paint the text in the music, which he does with consummate skill and ultimate confidence in his Messiah choruses. Happy Easter.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, Part II, “Hallelujah”