Although his compositions are all but forgotten today, Sir Eugene Goossens (1893-1962) was considered a fresh and highly promising musical voice. At the height of his popularity as a composer in the 1920s and 30s, his music placed on par with that of his British contemporaries Ralph Vaughan William, Benjamin Britten, Malcolm Arnold, Arnold Bax, and Gordon Jacob.

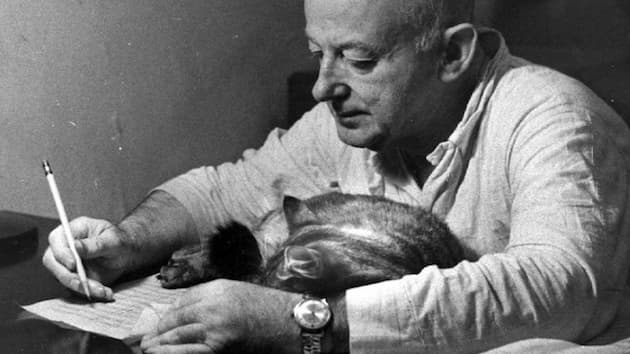

Sir Eugene Goossens

In all, he composed nearly seventy works, including chamber pieces, orchestral works and two full-length operas. Nevertheless, he established his name as a conductor when Sir Thomas Beecham, on short notice, engaged him in 1916 to conduct the opera The Critic by Stanford. His conducting skills were immediately recognised, as a critic wrote regarding a later concert: “He took command with complete assurance, and yet without ostentation, and his clear beat and simple indications to the players secured an admirable performance.” Prominent engagements with Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes and the Carl Rosa Opera Company at Covent Garden followed. He was referred to as “London’s Music Wizard,” and he assembled his own virtuoso orchestra in 1921.

Eugene Goossens: Variations on a Chinese Theme, Op. 1

By now, Goossens was internationally known, and he received an appointment from George Eastman to conduct the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra in 1923. The new orchestra was part of a brand-new school, the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Eastman was the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company, and “he endowed the new school and orchestra to encourage the appreciation of music through the popularity of motion pictures.” A couple of years later, Goossens was the sole music director of the symphony, and he taught conducting classes at the School of Music. He established Rochester as “one of the most important musical centres in America,” and in 1931, he departed for Cincinnati to serve as music director of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. The chairman of the board excitedly exclaimed, “We are fortunate to have secured Mr. Goossens’ services for the future, and we are looking forward with confidence to the further development of the orchestra.” Goossens succeeded Fritz Reiner as permanent conductor, and his “management was firm, but always based on an immense practical knowledge of instrumental technique and on his prodigiously detailed memory of a vast, wide-ranging repertoire.”

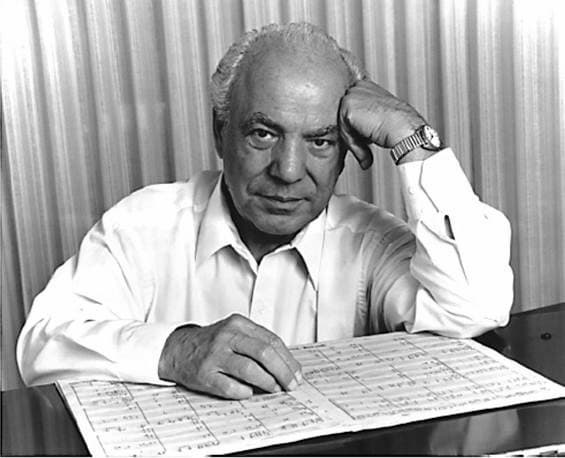

Henry Cowell

Henry Cowell: “A Fanfare to the Forces of our Latin-American Allies” (London Symphony Brass; Eric Crees, cond.)

On 7 December 1941, “a date which will live in infamy,” according to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the “United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.” America was going to war, and every part of American society participated. “Men and women enlisted in the military by the millions. Food and fuel were rationed. Businesses, factories, and workers stopped making cars and many consumer goods and instead manufactured aircraft, tanks, guns, bullets, and bombs. Even school kids pitched in, collecting scrap metal, rubber, and other materials needed for the war effort.” The artistic community followed suit, and Eugene Goossens commissioned 18 composers to write dedicated fanfares. As the conductor explained, “these rousing, short musical pieces feature brass and percussion in all their ferocious glory. It is my idea to make these fanfares stirring and significant contributions to the war effort.”

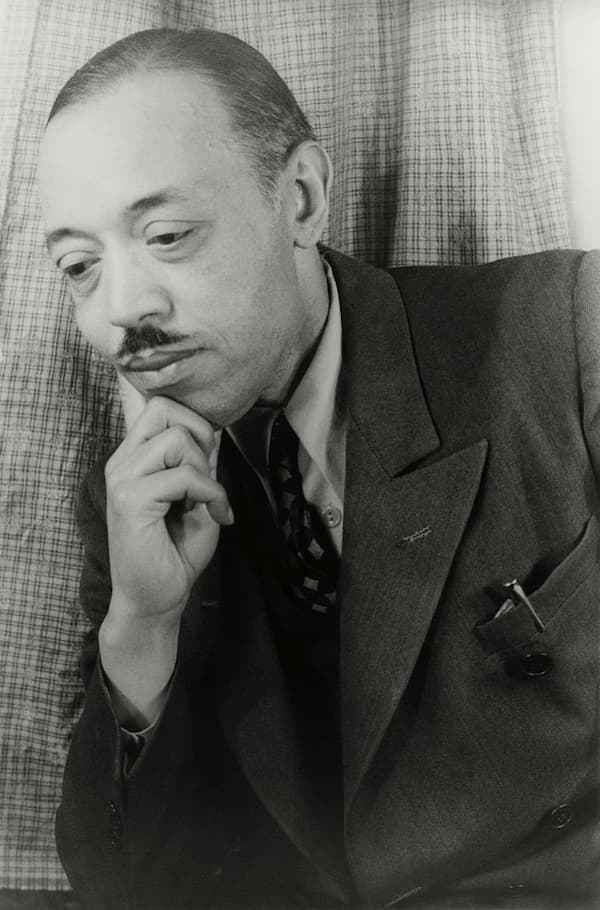

Paul Creston

Paul Creston: “A Fanfare for Paratroopers”

Some of America’s finest composers sprung into action, and the 18 fanfares played, one each week, during the 1942-43 season. We find “A Fanfare for Russia” by Deems Taylor, “A Fanfare for the Fighting French” by Walter Piston, and “A Fanfare for Friends” by Daniel Gregory Mason, and the “Fanfare de la Liberté” by Darius Milhaud. William Grant Still composed his “Fanfare for American Heroes” “in memorial for the coloured soldiers who died for democracy.”

William Grant Still

Still was in pursuit of what he called “Double Victory,” the victory against fascism abroad and racism at home. With this musical epitaph, Still clearly and poignantly reminded his listeners that “African Americans were equal in sacrifice for the cause of democracy, even as they were unequal in their access to its powers.” Grant Still composed in a modern but still accessible musical language. His fanfare introduces a solemn melody in the English horn that originated in the pentatonic language of the African American spiritual. “This is the true focus of Still’s work, not the fanfares that remain in the distance, and it serves as both a memorial and a reminder that the work is not yet done.”

William Grant Still: “A Fanfare for American Heroes”

Virgil Thomson, Morton Gould, Howard Hanson, Felix Borowski, and Eugene Goossens contributed additional fanfares, but the fanfare to achieve lasting fame was written by Aaron Copland (1900-1990). Copland had considered various names for his fanfare, including “Fanfare for the Spirit of Democracy,” “Fanfare for the Rebirth of Lidice,” and “Fanfare for Four Freedoms.”

Aaron Copland, 1942

In the end, the composer recalled, “I sort of remember how I got the idea of writing “Fanfare for the Common Man.” It was the common man, after all, who was doing all the dirty work in the war and the army. He deserved a fanfare.” The work premiered on 12 March 1943 and seemed to capture the notion of people “bravely joining forces to stand against danger.” It immediately struck a chord with the American public and is still heard at political rallies, sporting events and movies today. Recognising the popularity of his Fanfare, Copland reused the melody in his Third Symphony. Several decades later, Joan Tower composed her “Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman,” paying tribute to “women who take risks and are adventurous;” what a great topic for a follow-up article!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Aaron Copland: “Fanfare for the Common Man” (London Symphony Brass; Eric Crees, cond.)