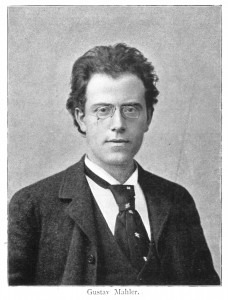

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler

Symphony no.2 in C minor “Resurrection” (1894)

After conducting a performance of Carl Maria von Weber’s comic opera Die drei Pintos (The three Pintos) on January 20, 1888—with Peter Illyich Tchaikovsky in the audience—Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) went home and staged his own funeral. Lighting numerous candles and surrounding his bed with flowers and wreaths received after the performance, Mahler lay in bed and imagined himself on his funeral bier. On some level, this act of theatrical morbidity undoubtedly reflects the composer’s experiences with loneliness, isolation and death, and in a therapy session with Sigmund Freud in 1910, the father of psychoanalysis had plenty to say about this gesture. Of course, we all remember that Gustav was the second of 14 children of whom only 6 survived into adulthood. He later explained that growing up meant to be part of “a funeral very other week”. However, in order to discover the real motivation behind Mahler’s thespian memorial service, we don’t have to go back to his childhood, but merely to his arrival in Leipzig in 1886.

After appointments in Bad Hall, Laibach, Iglau, Olmütz, Kassel, and Prague, the aspiring Gustav Mahler was appointed assistant conductor to Arthur Nikisch at the theater in Leipzig. In the course of getting to know his environment, Mahler met a captain in the Saxon army who turned out to be the grandson of Carl Maria von Weber, an essential musical figure in the development of Romantic opera in Germany. Apparently, Carl von Weber was in possession of musical sketches for Die drei Pintos, an unfinished opera by his grandfather. Carl and Gustav quickly agreed to bring this work to completion, and Mahler began to transcribe and orchestrate these sketches. While he was feeling his way around these musical drafts, however, he was also feeling his way around Carl von Weber’s wife. Marion Mathilde von Weber, in her mid-thirties and mother of three children, was born in Manchester in 1856 as Marion Mathilde Schwabe. Her extended German-Jewish family was intricately connected to the musical and cultural life in Manchester. According to some reports, her aunt lent money to Richard Wagner, her uncle organised Chopin recitals in the greater Manchester area, and Marion once performed with Joseph Joachim in a private setting. At some point, Marion departed for Leipzig, converted to Catholicism—just as Mahler would do in 1897—and married the debonair Carl von Weber.

Once Gustav arrived at the scene, they engaged in an intensely passionate affair. He was working on the sketches during the afternoon, and she was working on rearranging his hair after midnight. Rumour had it that Gustav asked Marion to elope with him, and that he had purchased a pair of train tickets to eternal happiness. For one reason or another, however, Marion did not appear. Urban lore even suggested that a jealous Carl, looking for his philandering wife, ornamented the departing train with a variety of randomly spaced bullet holes. In either case, it soon became obvious to Gustav that Marion was not going to leave her husband and children. Conducting the reconstructed Die drei Pintos in 1888 signaled the conclusion of a project that brought him professional recognition and praise, yet it simultaneously dashed any hopes of escaping with his beloved. The macabre staging of his own burial, as such, was the immediate reaction to this painful realisation. Apparently, Marion did follow Gustav home almost immediately, and after clearing away the flowers and wreaths, raised him from the dead! This curious little episode inspired Mahler to draft an extensive orchestral movement, originally entitled Totenfeier (Funeral Rites). Imparting a sense of impatience and unsteadiness, this enormous funeral march would subsequently become the first movement of his “Resurrection” Symphony. According to Mahler, the movement represents “a dirge wherein the hero of my First Symphony is borne to the grave”. Since we all know that the hero of that first symphony was Mahler himself, the music—and his relationship with Marion— provides fascinating insights into the emotionally and psychologically fragile world of Gustav Mahler.