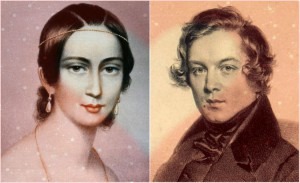

Robert and Clara Schumann

Clara Schumann: 3 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 16

But it was actually Robert’s deep emotional crisis and complete physical breakdown in 1844 that triggered the joint counterpoint ruminations. Robert gave up his editorship of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, a position he had held for over 10 years, and moved his family from Leipzig to Dresden. Once his health had improved, joint counterpoint studies were seen as occupational therapy to acquire emotional discipline. “Even for me,” Schumann writes to Mendelssohn, “it is a strange and wonderful fact that almost every motif which forms within me bears the characteristics for multiple contrapuntal combinations.” The result of this “Passion for fugues,” was a number of works in the strict style composed by him and composed by her! From Robert’s pen sprang Studies in the Form of Canons for Organ or Pedal Piano Op. 56, Sketches for Organ or Pedal Piano Op. 58, Six Organ Fugues on BACH Op. 60, and Four Fugues Op. 72. Clara concurrently composed her 3 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 16.

Robert Schumann: 4 Fugues, Op. 72

Schumann held back his Op. 72 for four years before allowing them to be published. Apparently he believed the “fugues are less popular, though I would like to indicate that you will not find in them the dry form of fugue; they are, at least as I believe, character pieces, only in stricter form.” As for Clara’s Op. 16, Robert offered the work for publication to Breitkopf and Härtel. He believed that they would be of particular interest to the public because, at that point of time, fugal composition was considered the embodiment of the male intellect. Despite Clara Schumann’s own doubts regarding her creativity, the best of her contemporaries praised and greatly valued her work. Franz Liszt, for example, wrote : “her compositions are really very remarkable. There is a hundred times more ingenuity and true sentiment in them than in all the fantasies past and present, of Thalberg.” In general, however, the neglect and downplaying of Clara Schumann as a composer was perhaps the chief disaster of the nineteenth century’s prejudice against female composer. Because, when listening to Clara’s Op. 16 and Robert’s Op. 72 side by side, it becomes clear that the couple shared an intimate and reciprocal generative relationship. And it was all based on a mutual love of J. S. Bach and of each other. Sometimes, life does not get any better!