“For Our Generation Walks as in Hades, Without the Divine”

Hölderlin Monument in the Alter Botanischer Garten Tübingen

German idealist poets and thinkers working in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were primarily concerned with the descent of the French revolution into Bonapartism, noting Germany’s failure to participate in the revolutionary Zeitgeist. It eventually grew into a political movement stretching from Goethe to Schiller, Hegel, Schelling, Fichte, and Novalis, who took up the question “what it is to become fully human.”

Peter Cornelius

For many literary critics, it was Friedrich Hölderlin who gave form to many of these thoughts and philosophies. Instead of promoting a static model of history, he reworked the classical tradition of ancient Greece, which “emphasized that everything is in flux.” Hope springs eternal, because it emerges from the fundamental human desire to make things better. Thinkers like Marx and Nietzsche, and a good number of composers subsequently took up that idea of eternal hope, plus or minus its religious connotations. Peter Cornelius (1824-1874) composed under the spell of Wagner and of Liszt, and the Hölderlin “Sunset” is an “orchestrally structured hymn of Brucknerian pathos.”

Where are you? Where are you? Drunkenly, my soul awakens

from all your pleasures, I harken now,

to the golden sounds

as the enchanting sunbathed-boy

plays his evening-song on the heavenly lyre.

His song rings through the tinted hills and forests,

though he is far away from the good folk,

who still honor him in his absence.

Peter Cornelius: “Sonnenuntergang” (Hans Christoph Begemann, baritone; Matthias Veit, piano)

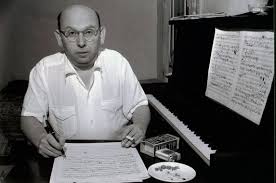

Hanns Eisler

Considered by many to be the “greatest ode poet in the German language,” Hölderlin’s poems were predictably used as patriotic songs in Nazi Germany. In popular musical settings of two prominent examples, “Death for the Fatherland,” and “Song of the Germans,” the interpretation is supported by marching rhythms and great jubilation on words like “Battle.” However, in the hand of Hanns Eisler (1898-1962) Hölderlin poetry is used to counteract the National Socialist indoctrinations. “It is quite astonishing,” wrote Bertolt Brecht, “how you take the plaster off Hölderlin.” In order to make his settings more topical and up-do-date, Eisler shortened Hölderlin’s poems and even gave them different titles. He also eliminated all suggestions of the word of antiquity and musically placed them in the late Romantic traditions. The relationship between text and music is deliberately organized, however, at times in mutual conflict.

Hanns Eisler: 6 Hölderlin Fragments (Dietrich Henschel, baritone; Axel Bauni, piano)

Walter Braunfels

At the Nuremberg rallies, Adolf Hitler proclaimed, “It is not the mission of art to wallow in filth for filth’s sake, to paint the human being only in a state of putrefaction, to draw cretins as symbols of motherhood, or to present deformed idiots as representatives of manly strength.” These callous words gave rise to the term “degenerate art,” used to ban and prosecute artists that did not fit the Third Reich’s narrow aesthetic and racial prescriptions. Modernism was not just an inferior or distasteful style, but a swindle and dangerous lie perpetuated by Jews, communists, and the insane to contaminate the body of German society. And the composer Walter Braunfels (1882-1954), son of a great-niece of Louis Spohr and listed as “half-Jewish,” fell under the modernist umbrella. His early works sounded at the 1905 Essen Festival of Contemporary Music, and he kept exploring vocal and dramatic genres. Among his orchestral songs are the Two Songs on Poem by Hölderlin, composed between 1916 and 1918. Braunfels was wounded in the Great War, and his experiences—alongside a sense of inner peace—are musically encoded in the Hölderlin ode “An die Parzen,” (To the Fates) and “Der Tod für’s Vaterland.”

Walter Braunfels: 2 Gesänge, Op. 27 (Paul Armin Edelmann, baritone; Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Gregor Bühl, cond.)

Grant me only one summer, Powerful Ones!

Only one summer and fall for my song to mature:

willingly then, and filled with the sweetness

of play, my heart shall consent to its death.

Souls deprived in their life of their God-

given right shall not rest in the underworld either.

But if the sacred I gain, the one

that’s close to my heart, the song of my poem,

welcome then, silent world of the shadows!

I’ll be at peace, though accords of my lyre

will not escort me below. For once

I lived like the Gods, and no more is needed.

Paul Hindemith

Scholars have long assumed that song composition played no part for Paul Hindemith during the late 1920s and 30s. However, a large collection of unpublished songs—composed between 1923 and 1929—was found in the composer’s estate. During this period, Hindemith is primarily setting German lyrics, including “To the Fates” by Hölderlin. For one, Hindemith was revising the idea of Romanticism, yet simultaneously bringing his compositions into the private realm. Freed from the restraints of political and social reality, Hindemith gained a new dimension of musical language through his reading of Hölderlin. He developed, just like the poet, the tension between subjective lyrical sound and a binding musical system, one that is withdrawn from the ever-changing conditions of time.

Paul Hindemith: 6 Lieder (Markus Schäfer, tenor; Christian De Bruyn, piano)