Pianist Krystian Zimerman (b. 1956) expanded his repertoire from solo piano (after winning the IX International Chopin Piano Competition in 1975) to duo works, working with violinist Kaha Danczowska in 1977 and recording Franck’s Sonata and Szymanowski’s Mythes together. More work with larger ensembles led him to the idea of quartets – 4 people playing together. Now, he has a collection of more than 500 quartets for piano and three other people, for a variety of instruments.

Krystian Zimerman

In his new GC recording, he and three string players, Yuya Okamoto, Maria Nowak, and Katarzyna Budnik, came together to play Brahms’ Piano Quartets Nos. 2 and 3. The String Quartet No. 1 in G minor is the best known of Brahms’ 3 quartets, but Zimerman wanted to avoid that evergreen and, instead, focus on making Nos. 2 and 3 ‘the most famous!’.

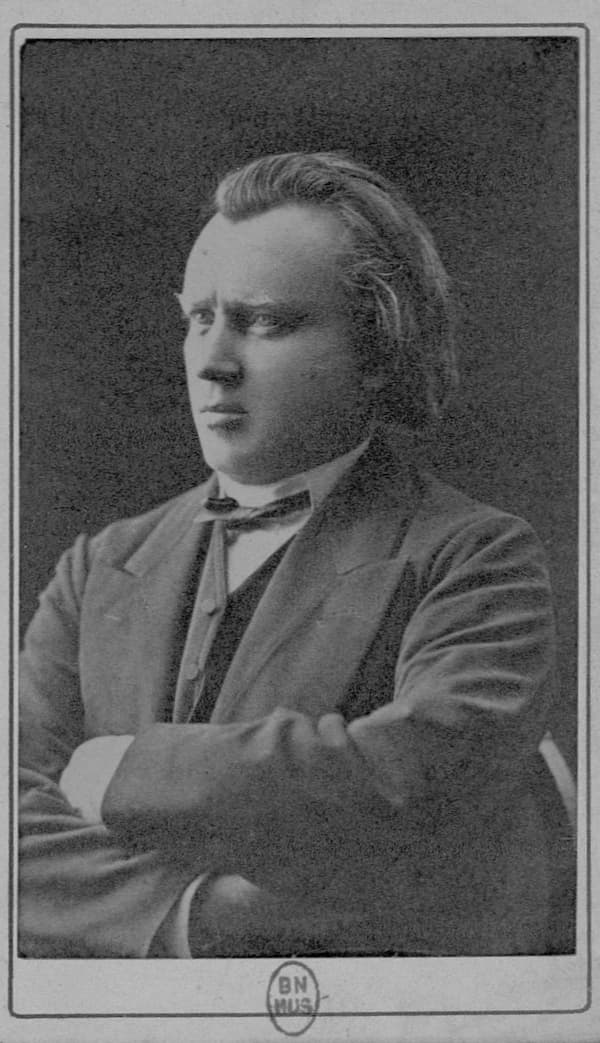

Johannes Brahms in 1872 (Gallica: ark:/12148/btv1b84160058

The ensemble came together accidentally. Violinist Maria Nowak had worked with Zimerman as the 2nd concertmaster in the Polish Festival Orchestra, which he had formed in 2010 for a tour of the Chopin concertos to commemorate the Chopin Bicentenary. Katarzyna Budnik plays in the Sinfonia Varsovia as lead viola, and he met cellist Yuya Okamoto when he was playing in a competition.

The Ensemble

Once his quartet was assembled and he’d persuaded them to look further into Brahms, they started to work.

Brahms wrote the Piano Quartet in A major, Op. 26, in 1862. When it first appeared, it eclipsed the first piano quartet of 1861 in popularity. Like so many of Brahms’ works, it has an expansive character while the quartet ensemble still keeps everything close and intimate. It has a lyricism that the 1st Piano Quartet in G minor lacks, and the use of sonata form in three movements helped Brahms develop his hand for extended forms.

The first movement contrasts triplets in the piano with flowing quavers (eighth notes) in the strings, using these two differing rhythms separately. In the end, however, they balance.

The second movement takes in elements of gypsy music that first appeared in the 1st piano quartet. The piano has a tranquil opening that is very song-like, while the strings are held back with mutes. The piano’s opening gradually becomes more and more florid with decoration. It’s not until the return of the main section that the strings can open up.

The third movement is built on melodies. It’s not quite a scherzo, despite its name, not having the abandon we associate with Beethoven’s scherzos, but unlike Beethoven, who relied so heavily on rhythm for his drive, Brahms uses the arc of his melodies to span vast territories. The contrasting trio section introduces even more of the Hungarian styling that was so important to the finale of the 1st Piano Quartet. It may be bright and fiery, but it’s also a strictly disciplined canon between the piano and the strings.

Unlike most final movements that are rondos, this one returns to sonata form. Hungarian rhythms predominate (and remind one of the 1st Piano Quartet finale). However, Brahms’ education in expansive forms, which he was learning from his study of Schubert, comes to the fore, and we have a movement that is full of relaxed strength rather than an overstated chest-pounding.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 2 in A Major, Op. 26 – IV. Finale: Allegro

Although it is called Piano Quartet No. 3, it was actually one of the first he started working on, but left unfinished in 1855. Twenty years later, he picked up the abandoned C sharp minor quartet, dropped the key to a mere C minor, and it became his Op. 60. He recomposed the finale and made it the scherzo movement, wrote a new Andante and a new finale.

There are some implications in Brahms’ writing that it’s a musical version of the highly dramatic Sturm und Drang epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, written in 1774 by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. When you think of the Werther story, which can be summed up as the life and suicide of a young man who is in love with a married woman whose husband he admired, parallels can be drawn with Brahms’ situation with Clara and Robert Schumann. Brahms loved Clara, but even after Robert’s untimely death, she refused his desire for marriage. Clara Schumann had been the pianist at the premiere of his Piano Quartet No. 1 in 1861, and it was Brahms who was the pianist for Piano Quartet No. 1’s premiere in Vienna on 18 November 1875.

Brahms has reached deeply into the Romantic musical vocabulary for this work. The first movement seems to have a 2-note theme that can be heard as ‘Cla-ra’ and which rapidly becomes a transposed version of Robert Schumann’s own Clara-motif. The transition is stormy and the development even more wrathful, and after the recapitulation, the coda doesn’t seem to draw things to a close as much as lie down in exhaustion.

The Scherzo movement (which had been the original draft’s finale), opens with a bold statement that rapidly rises, muttering, with rhythmic drive. The second theme is highly contrasting and chant-like. Unlike most scherzos, there is no contrasting trio section in the middle, but comes to an abrupt ending.

In the third movement, it is the cello that comes to the fore, with a song-like theme that soon becomes a duet with the violin. Here’s the calm center to this very fraught work.

The finale returns us to a state of unrest. The violin takes the solo position against an agitated accompaniment. The ideas are unsettled, the piano seems to be offering, at times, cynical commentary on the goings-on. The second theme, which sounds like an odd religious chorale, comes back in the recapitulation in the piano, which hammers out the chorale in a distinctly non-religious sense. The whole builds to the final cadence, which ends suddenly; could be that final gunshot that ended the unhappy Werther’s life? Final or not, the ending is curiously unsatisfying, rather a fatalistic response to the complications of life, perhaps.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60 – IV. Finale: Allegro comodo

The performance will make you rethink the two piano quartets. The cheerful optimism of the 2nd piano quartet will bring it back to its place in the repertoire. The unsettled aspect of the 3rd piano quartet may keep it out in the wilderness for some more time. Each of the performers has a place in the dialogue of the four. The piano tends to take the lead, but that’s not unexpected in a work by a piano virtuoso. The violin, viola, and cello each have starring roles, handled with skill and expertise that shine when required and provide solid support when in the background.

Listen to these works by Brahms with a new appreciation for what he was accomplishing and see if Brahms’ more delicate voice in the 2nd piano quartet, and his way of indicating a situational unhappiness in the 3rd piano quartet, move them up on your playlist.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartets Nos. 2 & 3

Krystian Zimerman, Maria Nowak, Katarzyna Budnik, Yuya Okamoto

Deutsche Grammophon 4864650

Release date: 5 April 2025

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter