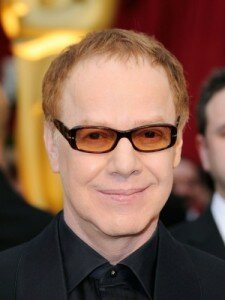

Danny Elfman

But it’s his classical music we want to look at. A few years ago, Mr. Elfman discovered the freedom of writing for orchestra without a film driving the inspiration. His works have included Serenata Schizophrana (2005), Rabbit and Rogue (2008) for choreographer Twyla Tharp, and the music for Cirque du Soleil’s Iris (2011). Following a performance in Prague of his Music from the Films of Tim Burton, he was commissioned to write a violin concerto.

He faced a fundamental audience problem: the audience for film music was a very different audience than the one for classical music. In his 2017 Violin Concerto, Eleven Eleven, jointly commissioned by the Prague Proms, the Stanford University Symphony, and the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, he tried to write a work accessible to both audiences: one that had ‘enough energy and melody’ to keep the film audience engaged while being ‘complex and varied’ enough for his classical audience. And, of course, to write music that was true to his own voice as a well-known film composer.

He set up a set of arbitrary rules to govern his composition:

• The piece would be four movements

• The outside movements (I and IV) would share thematic material and be the most Romantically influenced

• The inner movements (II and III) would be contrasting

• There would be a cadenza for the violin soloists and 4 percussionists

Sandy Cameron

The slow opening of the first movement could be nearly any scene-setting music film – but what’s unusual is that it’s the violin that’s setting the scene. The rest of the orchestra is the background to this first solo excursion. Having set the scene with the Grave section, he follows this with a contrasting Animato, where the violinist really shines. Can we hear film music in here or is it as romantic as he declares? Perhaps it’s the influence of all his Tim Burton films, but the occasional appearance of the marimba and other percussion sounds seem to move this more into the cinema than the concert hall.

Elfman: Violin Concerto, “Eleven Eleven”: I. Grave – Animato (Sandy Cameron, violin; Royal Scottish National Orchestra; John Mauceri, cond.)

The second movement, Spietato (Ruthless), is indeed a driving movement. First tip-toeing and then, sweeping up the violin and orchestra together, culminates in an extensive cadenza for violin and four percussion. It’s more like an accompanied cadenza, since only the violinist has the true cadenza qualities and the percussion are more like the background and accent for the violinist’s work. Second movements in concertos are normally at a slower tempo, a time to let the soloist show a lyrical side, but not here. This movement, however, doesn’t sound like it’s going anywhere.

II. Spietato

We finally get some respite in the third movement. We’re not resting, but nearly asleep in its luscious harmonies. About halfway through, however, the violin wakes up and things become much more interesting. It is a movement entitled Fantasma (Ghost or Shadow), and the violinist sometimes has a very shaded sound, muted and hidden. It doesn’t end as much as fade away.

III. Fantasma

The fourth movement, with its contrasting title of ‘Giacoso – Lacrimae’ (probably a misspelling of Giocosa (Playful) and Tears), surprises us with its almost Bernstein-sounding opening. It’s a beautiful modern work with scenic elements, emphasized by the percussion again, that are again quite cinematic. Final movements of concertos are generally the showcase movement – the last chance the soloist has for impressing the orchestra, the audience, and the world. Here, however, the Lacrimae / Tear section leaves us in a gradual decrescendo. Just as in the second movement – there’s a fading away at the end – but now it’s just the soloist, standing alone.

IV. Giacoso – Lacrimae

You don’t have the classical concerto duality here of Violin Versus Orchestra / Violinist And Orchestra. Neither is trying to convince the other of the superiority of its melodies, as you hear in some concertos, particularly from the classical period. This is a nice try at a concerto, but with too little attention paid to the standard format of a concerto, with three contrasting movements, with the form of those movement, with the duality of the violinist’s role for and against the orchestra, this comes across as an extremely virtuosic work for violin and orchestra, but not a concerto.

The title, Eleven Eleven, came out of a question about the length of the concerto and a joke about his name: ‘elf-man’ (or in a more German spelling, Elf Mann) is eleventh man and the concerto itself is 1,111 measures long: Eleven Eleven!