Before we enter that hallowed space—the concert stage— there are the ritual last minute precautions—men: fly zipped, check; women: hooks and buttons fastened especially in the front, check; string players: extra strings, check; oboe and bassoon players: good reeds soaking in water, check; music, check; brass players: valve oil, check; flute and clarinet players: swabs, check.

But no matter how prepared we are, unforeseen calamities can and do occur in performance. Batons, mutes and bows slip out of hands clattering and careening down the stage and sometimes into the audience.

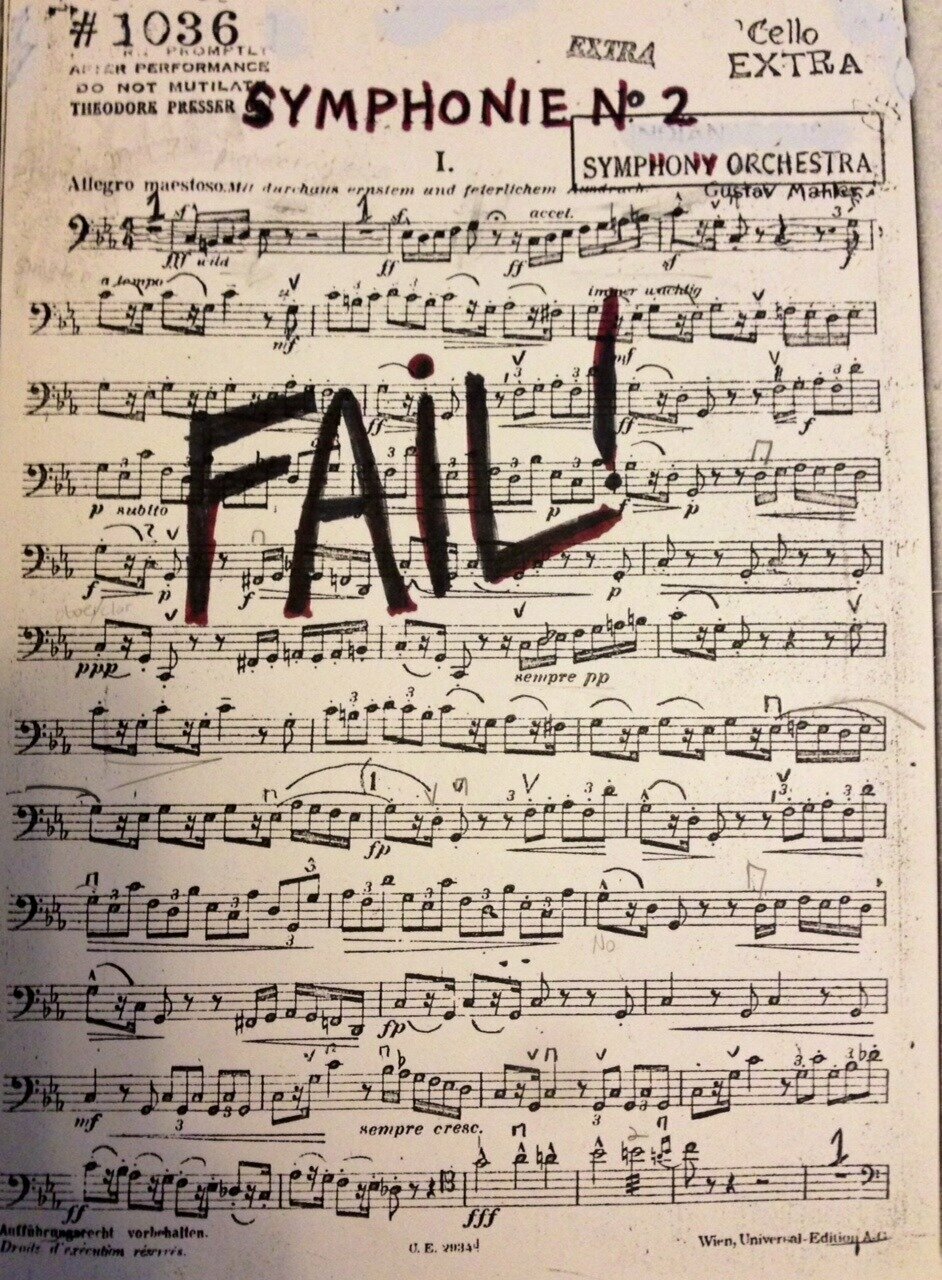

Usually we are prepared for the inevitable string snapping. If it is the soloist or concertmaster, someone will hastily trade violins and then a musician at the back will as unobtrusively and quickly as possible change the string. When it comes to a cello that is easier said than done. My six-foot-four stand partner had a knack for breaking even the thickest string—the C string causing an exploding sound, throwing the entire instrument out of whack. How did cellists react to broken strings on stage?

Guy Johnston BBC Young Musician of the Year 2000

Midori Goto

A famous “fail” occurred in 1985 when the then fourteen-year-old Midori had to swap her violin twice due to two broken strings during a performance with Leonard Bernstein. It was her Tanglewood debut with the Boston Symphony. She was performing the 5th movement of Bernstein’s own Serenade After Plato’s Symposium. In the heat of the action Midori broke the uppermost string—the E string. She quickly traded violins with the concertmaster. A few moments later she broke that violin’s E string. This time she was passed the associate concertmaster’s violin—all without missing a beat!

Midori “string fail”

Certainly I’ve witnessed some startling equipment failures. Yuri Bashmet, world-renowned violist, had a spectacular “fail” during a concert. He was playing his 1758 Testore viola. Suddenly the entire bridge, which holds up all the strings, literally exploded. Dazed, all he could do was shrug.

Yuri Bashmet’s 1758 viola falls apart during performance!

We musicians are often worried about falling: we might trip dodging all the onstage clutter of chairs, stands, microphones, instrument stands, and risers. Sadly, there have been several well-publicized falls of Maestros falling of their podiums James Levine included. Our principal guest conductor in the 1980’s, Klaus Tennstedt, who was a large man, once came tumbling off the podium toward me. I jumped up with my cello, and grabbed Tennstedt to steady him with the cello between us!

Conductor falls off podium

It was particularly horrifying when Itzhak Perlman fell in front of our eyes. Fortunately he was not hurt. Another violinist had carried Perlman’s violin. Perlman refused anyone’s help, got up, and then played brilliantly.

Conductor “fails” are more common. They are known to lose their tempers but rarely do the sparks fly as they did with Arturo Toscanini the great Italian conductor of the NBC Orchestra, who threw temper tantrums regularly. There are two famous stories of him actually causing bodily harm. Once, trying to mediate between two feuding musicians, Toscanini started pummeling one of the players with a ferocious intensity. Another time in Turin, in 1919, Toscanini snapped a musician’s bow near the violinist’s face causing injuries and narrowly missing the player’s eye. Despite apologies and some financial compensation the musician sued. Toscanini was acquitted.

Audiences cause concert “fails” too. Recently at a Toronto Symphony concert an elderly gentleman turned up his hearing aids to better hear the mesmerizing opening of the Shostakovich Violin Concerto played by Julian Rachlin. The cellos and basses begin very softly and in a low register. Then the violinist entered playing without vibrato—starkly. A very loud high-pitched squealing ensued. The conductor stopped the soloist and the orchestra, as the ushers scrambled to find the perpetrator. We sat quietly waiting until finally the gentleman was located and led out of the hall saying, “What’s going on? I can’t hear anything!”

An orchestral concert is not usually the site of fistfights, but there have been two of late. In March of 2012 Maestro Riccardo Muti was conducting a performance of Brahms Symphony No. 2. One usually sits motionless and restrained in symphony concerts, but that evening two men started fighting in one of the boxes. A 30-year-old man started punching an older man over a disagreement regarding their seats. Muti continued the concert during the melee, turning around to throw irritated glares at the perpetrators until they could be subdued. No one was charged.

During the first twenty minutes at the Boston Pops’ opening night of 2007, a scream was heard. Conductor Keith Lockhart gave the signal for the orchestra to stop. A scuffle had broken out in the balconies apparently after one man told another to be quiet. “House security and Boston police stopped the fight, and the audience members were escorted out of the hall,” the Boston Symphony Orchestra said in a statement. The concert resumed with cheers from the audience.

Ildebrando D’Arcangelo in Carmen © ROH/Catherine Ashmore, 2009

Opera patrons more often witness “fails.” One occurred during a performance with Sir Thomas Beecham who was known for his quick wit. In a 1930s production of Carmen at Covent Garden, live animals were part of the action. One of the horses proceeded to ‘do his business’ on the floor. “My God what a critic!” said Sir Thomas Beecham.

We try very hard to keep the show going on no matter what happens. The audience often is unaware of any mishaps onstage and they can enjoy the glorious music uninterrupted. But audiences do love the drama. Anything can happen at a concert hall!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I once saw Nicola Benedetti in a concert when one of the strings in her violin broke. The concertmaster came to her rescue, repaired it and she picked it up from where she had left off as if nothing had happened. Great presence of mind.

I recall an interview with Pablo Casals – this would have been about 1970. Casals recalled his debut in a German or Austrian city – perhaps Berlin or Vienna – as a very young man. He was playing a forgotten romantic concerto with a very dramatic entry from the soloist. Unfortunately, as he played his entrance, he let go of his bow and it went flying into the audience. Casals’ comment was that the audience was very serious and very understanding and no one laughed.