Toshio Hosokawa is widely regarded as one of the most prominent living composers of contemporary classical music. Born in Hiroshima, Japan, his compositions are distinguished by a unique synthesis of Western avant-garde techniques and traditional Japanese aesthetics.

Toshio Hosokawa

Hosokawa’s compositions reflect a deep philosophical engagement with nature, silence, and the transience of sound, influenced by Zen Buddhism and the Japanese concept of “ma,” the space between events.

Hosokawa remains an active composer, educator, and festival director, with a catalog of over 150 works to his name. His music continues to evolve, increasingly reflecting his Japanese heritage while maintaining a dialogue with Western traditions. His ability to weave personal, cultural, and universal themes into a cohesive and innovative sound world has made him a vital figure in contemporary music.

Toshio Hosokawa: Ancient Voices

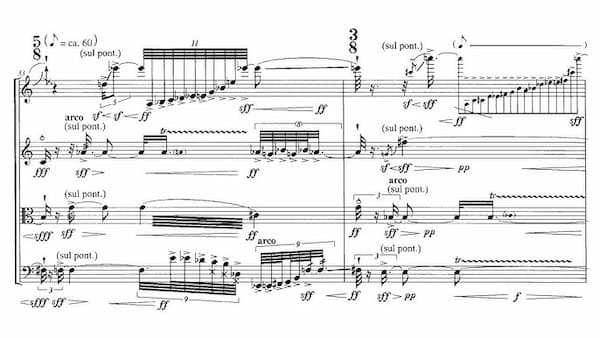

Études I–VI

Calligraphy

Composed between 2011 and 2013, Hosokawa’s Etudes express his Eastern-inspired aesthetic on the piano, an instrument he considers quintessentially European. These works are intimately connected with pianist Momo Kodama, who performed some of them for the very first time.

As the composer writes, “piano is an instrument from European music, and it is an extremely difficult instrument with which to express my musical language, which develops out of an Eastern mindset. These six studies are the études I wrote in order to challenge myself to learn how to realise my own original music on the piano.”

Hosokawa’s goal was not merely technical virtuosity but a deeper exploration of sound, silence, and gesture. Each étude bears a subtitle that reflects a specific idea or aesthetic, serving as a window into his creative process. These pieces were written and revised over a period of two years, and Étude I was commissioned as the required repertoire for the 58th Ferruccio Busoni International Piano Competition in 2011.

The Études are concise yet dense, demanding advanced pianistic technique, including rapid articulation, extreme dynamic control, and precise pedalling. All embody Hosokawa’s signature of “sound calligraphy.” He likens musical notes to “brushstrokes on a canvas of silences,” emphasising their individuality and the space around them.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude I, “2 Lines” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude I: “2 Lines”

Toshio Hosokawa’s Étude I, “2 Lines”

Hosokawa describes this piece as an exploration of “two independent lines that interweave and diverge.” In turn, this symbolises a dialogue or dance between distinct entities. Hosokawa connects this to calligraphic motion, where two strokes might overlap or separate on paper.

Owing to his musical background, counterpoint was “at first a highly difficult and not immediately accessible matter.” As a scholar writes, “perhaps this accounts for the insistence with which he sets contrapuntal processes in motion in music, again and again.”

The étude opens with two distinct melodic lines in the right and left hands, often in contrasting registers. These lines are rhythmically independent, creating a polyphonic texture that feels fluid rather than rigid. The use of chromaticism and microtonal inflections evokes the sliding tones of traditional Japanese instruments, while the dynamic contrasts are sharp and unpredictable. Both lines gradually fade into silence.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude II, “Point and Line” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude II: “Point and Line”

Hosokawa credits Wassily Kandinsky as the inspiration for the etude titled “Point and Line.” Specifically, he refers to Kandinsky’s book Point and Line to Plane. In his analogy to painting, Hosokawa explores the transition from a single point, in his case a static note, to a line as a moving gesture. He likens this to a calligrapher’s initial dot expanding into a stroke.

This etude opens with isolated staccato notes, clearly suggesting the “point” that gradually elongates into sustained tones or rapid scalar passages, the “lines.” Hosokawa provides for a sparse texture, with frequent silences that frame each gesture. According to scholars, this reflects Hosokawa’s Zen-inspired focus on the “birth and death” of sound.

Suggesting tension within simplicity, clusters and dissonant chords occasionally erupt. In essence, the interplay of single notes and linear motion creates a sense of organic growth, which Hosokawa likens to a plant unfurling. For the pianist, extreme precision in timing is needed to preserve silence and to control legato versus staccato articulations. And let’s not forget about the subtle pedalling needed to shape resonance.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude III, “Calligraphy, Haiku, 1 Line” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude III “Calligraphy, Haiku, 1 Line”

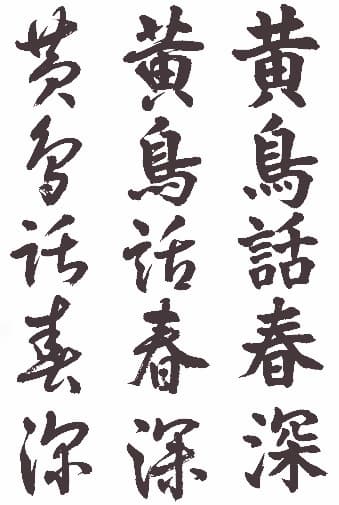

Japanese Calligraphy

The 3rd étude is tied to the brevity and depth of haiku poetry. This unrhymed poetic form consists of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 lines respectively. This tradition emerged in Japanese literature as a terse reaction to elaborate poetic traditions in the 17th century. Hosokawa views this etude as a “sonic haiku,” where one gesture encapsulates a world of meaning.

This etude focuses on a single melodic threat, unfolding with deliberate slowness. The line is ornamented with trills and grace notes, once again evoking the brushstroke flourishes of calligraphy. Silence plays a critical role, with long pauses inviting contemplation, and mirroring the structure of a haiku.

In an interview with Walter Wolfgang Sparrer, Hosokawa explained how difficult it was for him, as a Japanese musician, to hear in terms of functional harmony. The harmonic language in the haiku etude is minimal, with only occasional dissonant punctuations fading into resonance. In terms of performance, the pianist needs to sustain control of a single line, handle delicate ornamentations, and master silence through pedalling and timing.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude IV, “Ayatori, Magic by 2 Hands, 2 Lines” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude IV “Ayatori, Magic by 2 Hands – 2 Lines”

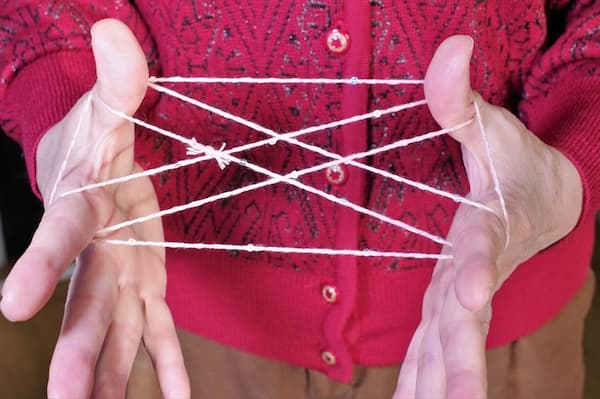

Ayatori

“Ayatori” is a traditional Japanese string game, similar to “cat’s cradle,” where two hands create intricate patterns using a string loop. Ayatori is generally played by one person, but it can also involve two people, who take the string from each other’s hands and make shapes. In this etude, Hosokawa uses this as a metaphor for the interplay of two musical lines manipulated by the pianist’s hands.

The music features two contrasting voices that twist and turn around each other, often in a playful and dance-like manner. The lines are rhythmically complex, with syncopated patterns and abrupt shifts in tempo.

The texture condenses at times into chordal passages, only to unravel into sparse, single-note exchanges. The piece ends with the lines converging into a unified gesture, suggesting the completion of the “magic” pattern. One thing for sure, the technical demands call for intricate hand coordination, agility in syncopated rhythms, and dynamic interplay between hands.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude V, “Anger-Fist-Storm” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude V “Anger – Fist – Storm”

This etude alludes to the destructive power of nature. Hosokawa describes it as “an expression of raw emotion. Anger as a primal force, akin to a fist striking or a storm raging.” True to its title, this is the most aggressive etude in the set, featuring pounding clusters, rapid repeated notes, and jagged rhythmic figures.

Extreme dynamics feature fortissimo passages that mimic the chaos of a storm. However, moments of eerie calm interrupt the fury, with soft, tremolo-like figures suggesting a lingering tension.

This etude unfolds in bursts of energy that dissipate into silence, “embodying the transient nature of rage.” It demands pianistic stamina for relentless prepetition, power for cluster chords, and great sensitivity for dramatic dynamic control.

Toshio Hosokawa: Étude VI, “Melody-Birds-Resonance” (Momo Kodama, piano)

Étude VI “Melody – Birds – Resonance”

Hosokawa connects this etude to the natural world, particularly to birdsong, which he sees as “a melody emerging from and returning to resonance.” Hosokawa’s music is deeply inspired by nature, which he sees as a source of spiritual energy and transience. By emphasising the interplay of sound and silence, each note carries symbolic weight and reflects the impermanence celebrated in Japanese culture.

This lyrical and expansive etude features a flowing melody in the right hand, accompanied by arpeggiated figures in the left. The melody mimics birdsong through trills, rapid runs, and sudden leaps. Sustained chords meanwhile create a shimmering backdrop. The piece builds to a climactic resonance before dissolving into a meditative close, returning to stillness.

Hosokawa’s Études are not merely technical exercises but meditations on sound as a living entity. He emphasises that his music captures the “process of how notes are born and die,” a concept rooted in Zen and the transience of Japanese aesthetics like cherry blossoms. For Hosokawa, the piano, with its percussive attack and decaying resonance, becomes a vehicle for this philosophy.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter