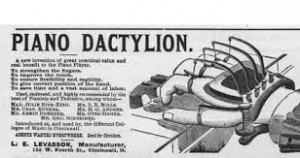

The opening decade of the 21st century is once more gripped by a passion for musical virtuosity. Countless young and aspiring musicians—frequently supported and driven by overzealous parents—are vying to study at the most prestigious conservatories and with the most esteemed teachers around the world. To the music historian, this kind of narcissistic frenzy is nothing new, as the rage for keyboard instruments at the beginning of the 19th century reached ever-new levels of insanity. Teacher invented a whole series of mechanical devices—more reasonably called torture devices—that could supposedly help a budding virtuoso achieve even greater finger agility. And Henri Herz patented one such contraption, called the Dactylion in 1836. Mind you, Herz was one of the most famous virtuosos and popular composers in Paris of the 1830s and 40s. He engaged in extended concerts tours to Russia, the United States and South America, and to supplement his income he kept an enormous stable of willing piano students.

The opening decade of the 21st century is once more gripped by a passion for musical virtuosity. Countless young and aspiring musicians—frequently supported and driven by overzealous parents—are vying to study at the most prestigious conservatories and with the most esteemed teachers around the world. To the music historian, this kind of narcissistic frenzy is nothing new, as the rage for keyboard instruments at the beginning of the 19th century reached ever-new levels of insanity. Teacher invented a whole series of mechanical devices—more reasonably called torture devices—that could supposedly help a budding virtuoso achieve even greater finger agility. And Henri Herz patented one such contraption, called the Dactylion in 1836. Mind you, Herz was one of the most famous virtuosos and popular composers in Paris of the 1830s and 40s. He engaged in extended concerts tours to Russia, the United States and South America, and to supplement his income he kept an enormous stable of willing piano students.

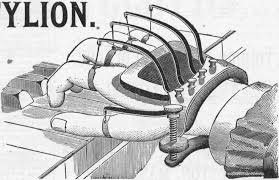

The dactylion was specifically designed to loosen and strengthen the fingers of would-be virtuosos. It was made up of two parallel wooden bars. The first was fixed to the front of the keyboard and guided the hands. The second wooden bar, placed parallel to the first, had ten rings. These rings, one for each finger, were attached to springs that could be adjusted to give greater resistance. Apparently, the device just flew of the shelves!

The dactylion was specifically designed to loosen and strengthen the fingers of would-be virtuosos. It was made up of two parallel wooden bars. The first was fixed to the front of the keyboard and guided the hands. The second wooden bar, placed parallel to the first, had ten rings. These rings, one for each finger, were attached to springs that could be adjusted to give greater resistance. Apparently, the device just flew of the shelves!

Henri Herz: Rondo de Paganini (Marco Pasini, piano)

A good number of musicians, however, were rather skeptical from the beginning. The pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner introduced François-Joseph Fétis, the first director of the Brussels Royal Music Conservatory, to the Dactylion. “It seems,” Fétis remarked, “that the Dactylion is only good for catching mice.” No, replied Kalkbrenner, “Monsieur Henri Herz made it for catching fools.” Robert Schumann was highly critical of Herz’s compositions, claiming that this music “exemplified the hollow state of the Parisian virtuosos.” But we also know that Schumann developed rather severe hand problems in the mid 1830s. Nobody knows if he actually bought a Dactylion, but he certainly made a contraption, probably based on the Dactylion that isolated one finger at a time. All that venom and spite against the Parisian virtuosos might, after all, have been the result of having been made a fool!

A good number of musicians, however, were rather skeptical from the beginning. The pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner introduced François-Joseph Fétis, the first director of the Brussels Royal Music Conservatory, to the Dactylion. “It seems,” Fétis remarked, “that the Dactylion is only good for catching mice.” No, replied Kalkbrenner, “Monsieur Henri Herz made it for catching fools.” Robert Schumann was highly critical of Herz’s compositions, claiming that this music “exemplified the hollow state of the Parisian virtuosos.” But we also know that Schumann developed rather severe hand problems in the mid 1830s. Nobody knows if he actually bought a Dactylion, but he certainly made a contraption, probably based on the Dactylion that isolated one finger at a time. All that venom and spite against the Parisian virtuosos might, after all, have been the result of having been made a fool!

Henri Herz: Deux études de Henri Herz