There are countless reasons why composers attached dedications to their scores. In a wonderful study, Emily H. Green has attempted to unravel the complex relationship between composers, publishers, and consumers of music. For one, works might be dedicated to patrons, sponsors, collaborators, colleagues, lovers, or simply friends.

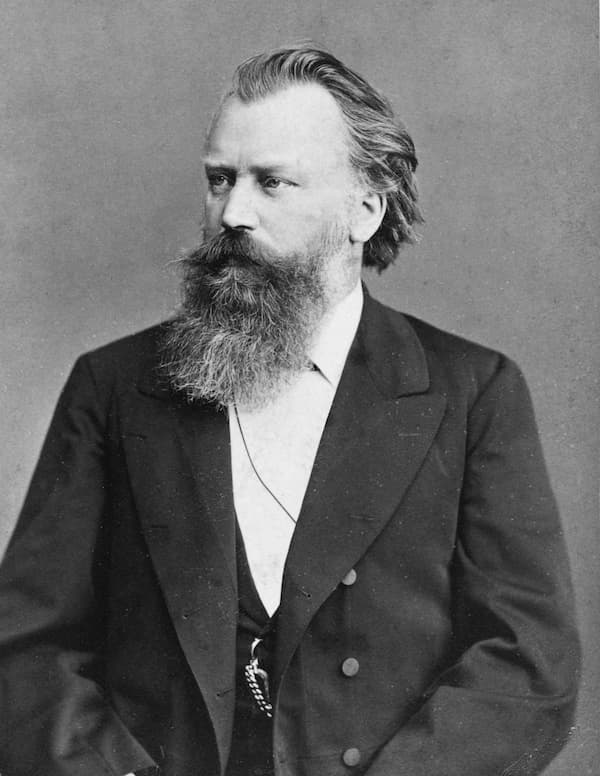

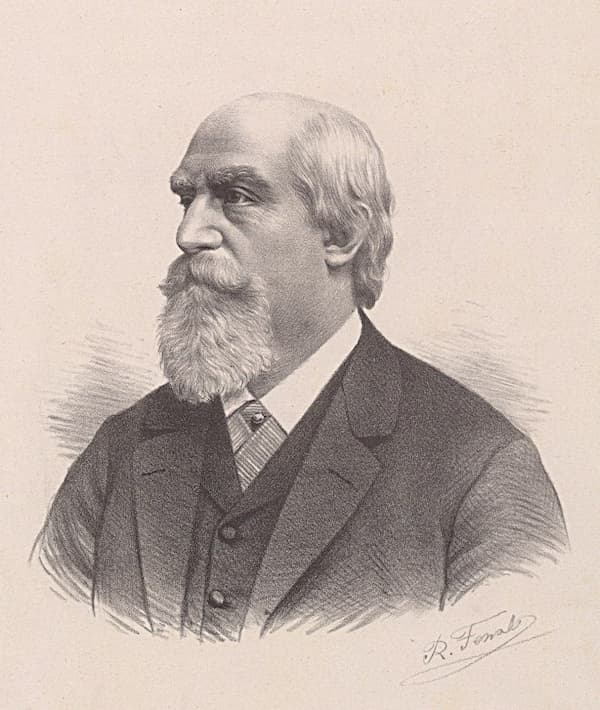

Johannes Brahms, c. 1885

Over time, the reasons for attaching specific dedications changed. According to Green, this “reflects a changing financial and aesthetic landscape in which patronage was waning and independent artistry surging.” On occasion, a dedication contributed to a new kind of branding of music, possibly communicating artistic or political allegiances. And, of course, we should never discount the opportunity for self-promotion.

Johannes Brahms was a painfully private individual whose music exerted a powerful influence on his contemporaries. Yet, Brahms’s music has always presented challenges because his achievements as a composer are not accessible by detailed knowledge of his biography. One thing is for sure: he never wrote into his work the soul-felt emotions of his life as an artist, or better yet, he never explained them to his listeners. However, he did, on occasion, attach dedications to his scores, which do provide some interesting listening signposts.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, Op. 83

Eduard Marxsen

Eduard Marxsen

We might as well start with the Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, Op. 83, a monumental work in four movements that represents an ingenious hybrid between the symphonic and concerto genres. Completed in 1881, the work is dedicated “to his dear friend and teacher Eduard Marxsen” (1806-1887). Marxsen started giving first lessons to the young Brahms in 1843, and his pianistic skills improved rapidly. In addition, Marxsen also taught Brahms some theory lessons and supervised his early efforts at composition.

Marxsen subsequently took credit for essentially discovering “a great new blossoming master in Brahms.” Actually, Marxsen was in competition with the violinist Eduard Reményi for that particular claim. Apparently, Marxsen had said to him, “Well, well, I am sorry for your judgement. Johannes Brahms may have some talent, but he certainly is not the genius you stamp him.”

Eduard Reményi

In his 1912 article, the Brahms student Gustav Jenner questioned if Marxsen had been the right teacher for the young composer. He writes, “Well intentioned though Marxsen undoubtedly was, he was incapable of instilling in Brahms the profound technical basis necessary to enable him to fully realise his innate gift for composition.”

Here, then, is what Brahms had to say about Marxsen, “The composition teacher to whom my father entrusted me had all the best intentions, and I will never forget that he refused the heavy purse of money my father had saved up to pay for my lessons… And I faithfully went there, but I learnt absolutely nothing.” In a case of actions speak louder than words, the Brahms dedication is certainly a striking token of devotion to his teacher.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor, Op. 2

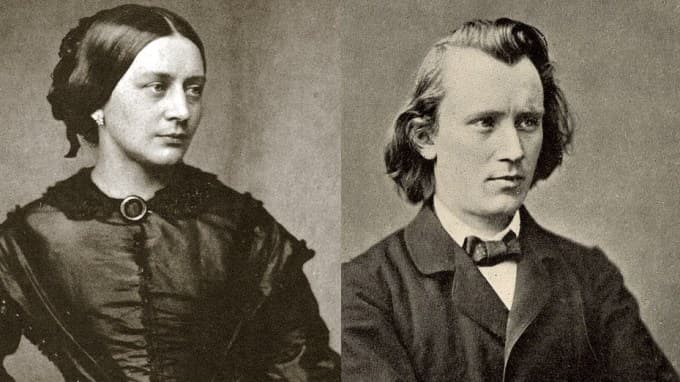

Clara Schumann

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms are surely the most famous love triangle in the history of Western music. Brahms first visited the couple in Düsseldorf on 30 September 1853, and he stayed for four weeks. Both welcomed him warmly, and Robert was highly enthusiastic about the young man’s compositions; he even called him a genius and the coming saviour of German music!

When Robert attempted suicide, Brahms rushed back to Düsseldorf and lived with Clara and the children in the Schumann house. However you look at it, Brahms was helplessly in love with Clara. He wrote in frustration in 1855, “I can do nothing but think of you… What have you done to me? Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me?” The situation was, to put it mildly, rather messy.

When Brahms first visited the Schumann’s, he brought with him a whole stash of compositions, among them a Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor. It was a huge and bold statement for a young composer full of ambition. The first piano sonata composed by Brahms makes grand gestures of dissonance and form, and it behaves more like a fantasy than a sonata.

It is no wonder that Robert Schumann liked the work and recommended it to his publisher, as abrupt shifts and contrasts sound like sudden bursts of passion. Brahms asked Schumann for permission to “set your wife’s name at the head of my work?” And in the earliest surviving letter addressed to Clara, Brahms writes, “I have dared to put your name at the head of the sonata. May you not find this as immodest as I now do; I hardly dare send it to you.” One way or another, the Brahms Op. 2 dedicated to Clara marks the beginning of a relationship that lasted almost forty years.

Johannes Brahms: Violin Sonata No. 3 in D minor, Op. 108

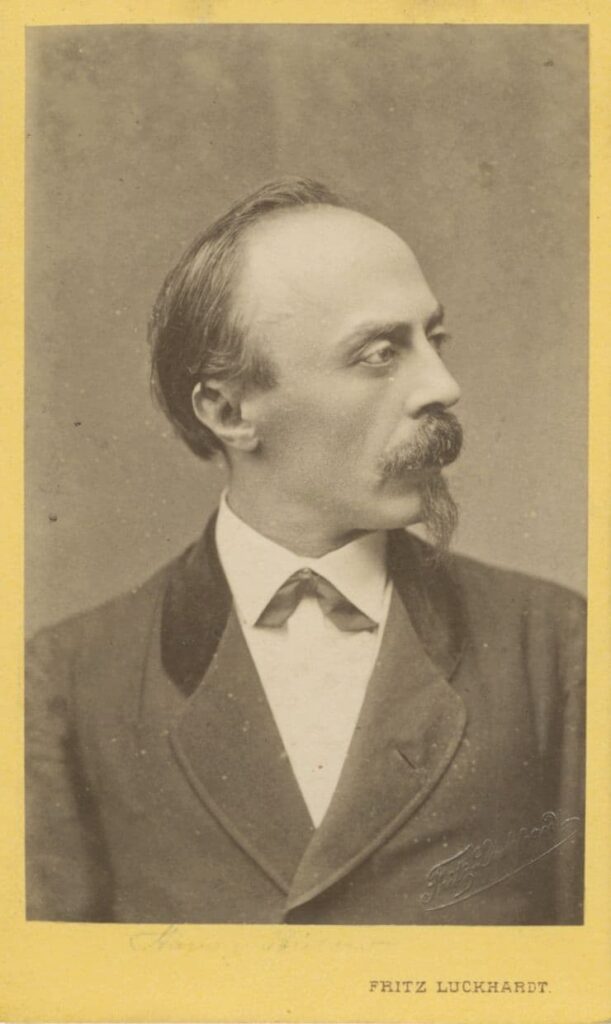

Hans von Bülow

Hans von Bülow

Brahms first met Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) through Joseph Joachim in January 1854. Bülow was apparently greatly impressed by Brahms’ musical talents, but once Joachim, Grimm, Scholz, and Brahms signed the manifesto against the “New German School,” things cooled down considerably. As he wrote in 1866, “after examining all of Brahms’ compositions with a really open mind during an entire week, I have concluded that his music is not to my taste.”

Yet, when Bülow conducted the First Symphony of Brahms in 1877, he immediately called it “Beethoven’s Tenth.” However, Bülow’s devotion to the music of Brahms comes from the time when he first heard the “Adagio” of the Second Symphony. According to Bülow, “this was an experience like St. Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus.”

Bülow was instrumental in spreading Brahms’ fame, especially with regard to his 4th Symphony. As Peter Clive writes, “Bülow conducted the work in 23 concerts in 23 days,” but once again, disagreements started to creep in. In his personal and artistic friendships, Brahms liked to push the boundaries, but habitually he apologised by composing a dedicated work to mend the relationship. And such was the case with his Third Violin Sonata, published in 1889.

Brahms publicly expressed his gratitude for Bülow’s friendship and support, and Bülow in turn, suggested that the city of Hamburg should award an honorary citizenship to Brahms. Shortly thereafter, Brahms presented the autograph of his Third Symphony to Bülow on the occasion of his 60th birthday. Brahms added the following inscription, “To his loved Hans von Bülow in faithful friendship.”

Johannes Brahms: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 51 No. 1

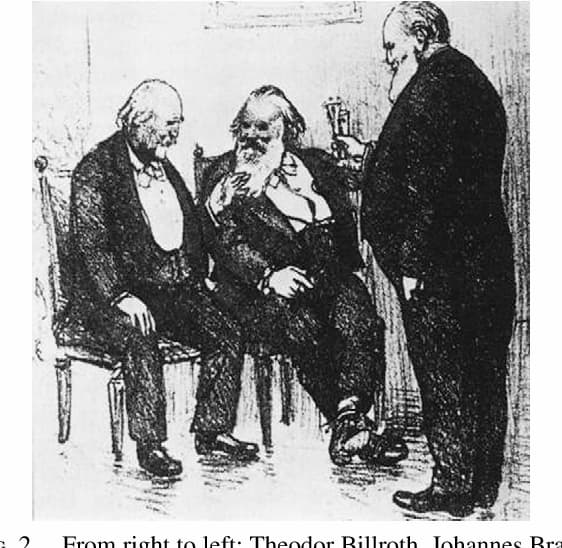

Theodor Billroth

Eduard Hanslick, Johannes Brahms, and Theodor Billroth

Called the “father of modern abdominal surgery,” Theodor Billroth (1829-1894) was directly responsible for a number of surgical landmarks. He performed the first esophagectomy in 1871, the first laryngectomy in 1873, and perhaps most famously, the first successful gastrectomy in 1881. Even today, several diseases and surgical procedures are named after him.

In the musical world, however, he is primarily remembered for his close friendship with Johannes Brahms. Brahms had a solid educational background but never went to University. Actually, he went a long way to keep that fact a closely guarded secret. As such, he enjoyed surrounding himself with highly educated people, yet his genuine friendship with Billroth lasted for decades.

Much of Brahms’s chamber music for strings was first performed in Billroth’s home, with the surgeon participating as a musician in trial rehearsals. Brahms would frequently send Billroth his original manuscripts for evaluation prior to publication. Of course, Brahms being Brahms, he happily kept ignoring all of Billroth’s suggestions. Nevertheless, Brahms did dedicate the two string quartets Op. 51 to his surgeon friend.

Billroth was overjoyed and responded, “I am afraid these dedications will keep our names longer in memory than the best work we have done. For us, it is not very complimentary, but beautiful for humanity, which, with the right instinct, considers art more immortal than science.”

Johannes Brahms: Waltzes, Op. 39

Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick

Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904) was an esteemed music critic writing for a couple of Viennese newspapers. He seriously attracted attention for his short 1854 treatise on the aesthetic aspects of music titled “The Beautiful in Music.” It was translated into several foreign languages, and Brahms initially considered the treatise to “contain too many silly statements that he put down without finishing it.”

Hanslick had originally met Brahms in 1855, and they established friendly relations after Brahms arrived in Vienna in 1862. Hanslick considered the Brahms Sonata Op. 5 “among the most deeply-felt pieces existing in modern piano music.” When Brahms became conductor of the Singakademie in 1862, Hanslick was highly enthusiastic. To return the favour, Brahms dedicated the Waltzes Op. 39 to Hanslick, assuring good professional relations.

However, Hanslick did not like a good many of works by Brahms, as he certainly did not have great admiration of the First and Third Symphonies, the Piano Trio Op. 8, or the Piano Quintet. Nevertheless, he championed Brahms’ music throughout his life, and in equal measure, detested most of Richard Wagner’s music.

Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann on the occasion of Hanslick’s 70th birthday, “I knew few persons for whom I feel as deep affection as I do for him. To be so naturally good, well-intentioned, honest, truly modest, and everything else I know him to be seems to me very fine and very rare.”

Johannes Brahms: 5 Lieder, Op. 49, No. 4 “Wiegenlied” (Renée Fleming, soprano; Hartmut Höll, piano)

Bertha (Porubsky) Faber

Bertha (Porubsky) Faber

Between 1859 and 1862, Johannes Brahms composed and arranged music for the Hamburg Women’s Chorus. They met once a week, with a smaller group of a dozen singers meeting for additional rehearsals. While making music was an important aspect of Brahms’ involvement, it was not the only one. There was also Bertha Porubsky, daughter of a Protestant pastor, who was spending a year in Hamburg.

Brahms and Bertha were sufficiently smitten to engage in lively correspondence, and Brahms wrote in 1859, “Most revered, dear friend, I wish you had seen my delighted face when I found your letters. The first lovely handwriting was already familiar, I had indeed looked upon it that last evening in Hamburg, and how often, since then…I am in love with music, I think of nothing but, and I am composing love songs again!”

Johannes and Bertha were clearly in love, however, in a pattern that would continue to repeat for the rest of his life, Brahms abruptly stopped all communication and withdrew from the relationship completely. When Brahms arrived in Vienna, he was much relieved to discover that Bertha was about to marry the rich industrialist Arthur Faber.

On the occasion of the birth of Bertha’s second son, Brahms wrote his most famous melody. Brahms sent the “Wiegenlied” (Lullaby), Op. 49, No. 4 to Bertha’s husband and wrote, “Frau Bertha will realize that I wrote the ‘Wiegenlied’ for her little one. She will find it quite in order that while she is singing Hans to sleep, a love song is being sung to her.”

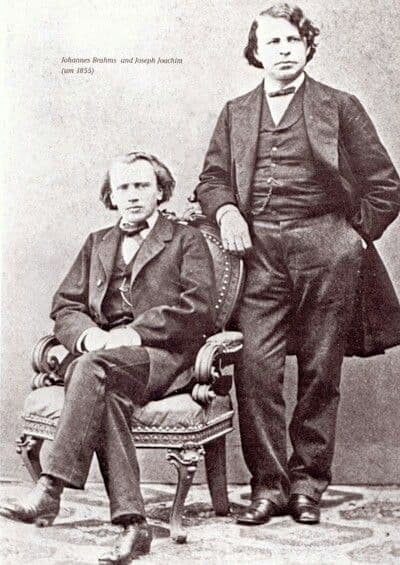

Joseph Joachim

Brahms and Joachim, ca 1855

The Hungarian violinist Joseph Joachim (1831-1907) is partially responsible for one of the greatest violin concertos in the repertoire. Brahms and Joachim engaged in a long artistic association that proved highly rewarding for both men. And Joachim was part of the violin concerto project from the very beginning.

As he did in the later Second Piano Concerto, Brahms was looking to blend solo and orchestral lines into a unified, symphonic texture. Originally, Brahms planned the composition in four movements, but he eventually reports to Joachim, “the two middle movements have fallen through.”

Since Brahms was not a violinist, he sent sketches of the solo part to Joachim for advice. He writes: “I wanted you to correct, and I didn’t want you to have any excuse of any kind; either that the music is too good or that the whole score isn’t worth the trouble. But I shall be satisfied if you just write me a word or two, and perhaps write a word here and there in the music, like ‘difficult,’ ‘awkward,’ ‘impossible,’ etc.”

Joachim worked painstakingly through the entire manuscript, and communicated his suggestions to Brahms, who characteristically ignored most of them. As a reward, Brahms entrusted Joachim to write the Cadenza for the first movement, which quickly became an integral part of the composition. Obviously, the Concerto is dedicated to Joachim who featured in the premiere on 1 January 1879 in Leipzig, with Brahms conducting.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter