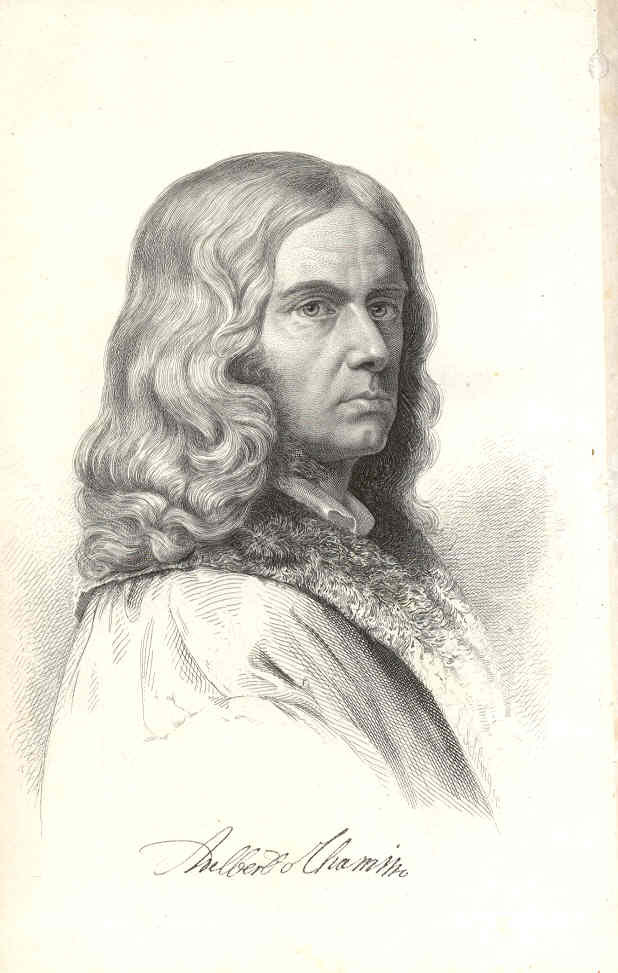

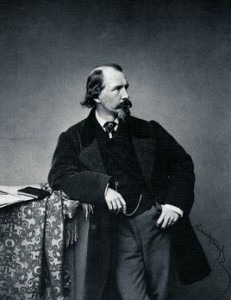

Emanuel Geibel, photograph by Franz Hanfstaengl

Schumann began work on the collection in 1849, at a time when he was writing music for male-voice and mixed-voice choirs in Dresden. We have to remember that in 1848, all of Germany was in uproar following the March revolution – it arrived in Dresden by May of 1849. Many activists, such as Wagner, had to flee the country and even the Schumanns took refuge in the outskirts of the city. These internal civil wars keep people home and what better than to write some ‘home’ music.

The poets for this Spanisches Liederspiel are anonymous. The source for the poetry was a book published in Berlin in the 1830s entitled Volkslieder und Romanzen der Spanier im Versmaße des Originals (Folksongs and romances of the Spaniards, in the metre of the originals). What’s more important is that the editor of the volume was Emanuel Geibel (1815-1884), who was an academic in Lübeck and a favourite writer of poetry for the German lied.

These are songs about love, but it’s not happy love – it’s melancholic love. Lovers sigh, are sleepless from hopeless grief, have their eyes clouded by sorrow and agony, and all those other torments of the romantic soul. One song, however, in the middle of the cycle, is happy, with a man teasing a woman, concluding “Und die Wangen offenbaren, / Was geheim im Herzen ruht.” (And your cheeks reveal / The secret of your heart.)

Schumann: Spanisches Liederspiel, Op. 74: No. 5. Es ist verraten (Marlis Petersen, soprano; Anke Vondung, mezzo-soprano; Werner Güra, tenor; Konrad Jarnot, bass-baritone; Christoph Berner, piano)

This amusing quartet is immediately followed by the solo Melancholie, where the poet awaits anxiously for morning, declaring that in his entire life, he hasn’t had a single cheerful hour.

No. 6. Melancholie

The whole cycle really moves the German lied in a direction probably unimagined by Schubert. It’s opera at home, drama to the accompaniment of a piano, and perfect for the mid-nineteenth century and its political restrictions on movement.