The musico-poetic work Façade: An Entertainment

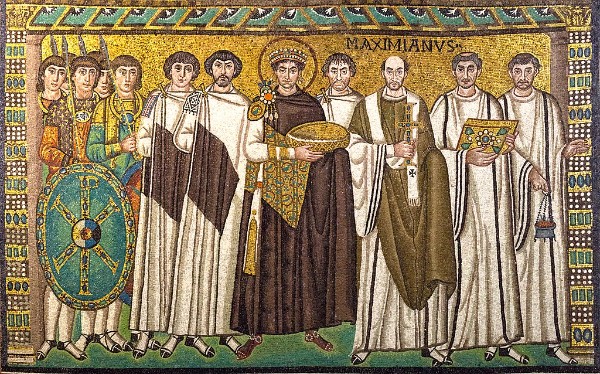

Roger Fry: Edith Sitwell, 1915

Called ‘the high priestess of 20th century poetry,’ English author Edith Sitwell used her experimental poetry to drive a dying form forward. Sitwell (1887-1964) filled her poetry with melody, new rhythms, and confusing private allusions. She saw that a change was necessary to counteract ‘the rhythmical flaccidity, the verbal deadness, the dead and expected patterns, of some of the poetry immediately preceding us.’ Her poetry was criticized for being rather too tied to symbolism as to make the symbols seem confused and indiscriminate, but others found it to have a ‘luxurious beauty.’

In 1922, her poetry was set to music by William Walton, or, perhaps another way of saying it would be that she recited her poetry (through a megaphone) to an astute musical accompaniment by William Walton.

The poetry was seen as nonsense, in the style of Edward Lear. A deeper analysis, however, showed that her poetry is filled with quick references that are highly organized. There are personal references, such as those to her mother (called here Mrs. Behemoth), bane of her unhappy childhood.

Edith Sitwell (standing) and a performer holding a Sengerphone

The musico-poetic work, entitled Façade: An Entertainment, had its first performance as a private presentation in the Sitwell’s drawing room in Carlyle Square, London. 18 numbers were done, with Edith Sitwell on her ‘Sengerphone’ – a megaphone designed for operatic use – and Walton conducting the ensemble.

The Sengerphone was a papier mâché horn that preserved the tonal qualities of the voice. The opening of the horn encompassed the mouth and the nose, so that the nasal resonance of singers would be amplified as well.

In its first public performance in London in June 1923, 24 numbers were done. The hall was filled with illuminati of the day, including Evelyn Waugh, Virginia Woolf, and Noël Coward, who was so angered by the poetry and the staging that he made a public and obvious exit during the performance. The critics were scathing, but one did admit that it was ‘naggingly memorable.’ Even Walton called it a disaster.

It opens with a fanfare and segues into a hornpipe:

William Walton: Façade 1 – I. Fanfare – Hornpipe (Peter Pears, speaker; English Opera Group Ensemble; Anthony Collins, cond.)

Piper curtain for Façade

The next performance was 3 years later, in 1926, with 26 numbers and it was a success. What is called the definitive version was staged in 1942, in 21 numbers, with Constant Lambert as the speaker and Walton conducting. The curtain that held the Sengerphone was designed by John Piper.

One of the effects that Sitwell was trying to capture in her poetry was the rhythm of dance forms, and we see this in works such as Tango-Pasodoble, which also includes the patter of seaside entertainments.

William Walton: Façade 1 – VI. Tango-Pasodoble (Peter Pears, speaker; English Opera Group Ensemble; Anthony Collins, cond.)

Other dance movements include IX. Tarantella, XII. Country Dance, XIII. Polka, XVI. Valse

William Walton: Façade 1 – IX. Tarantella (Edith Sitwell, speaker; English Opera Group Ensemble; Anthony Collins, cond.)

We gradually recognize the immense amount of skill it took to realize her poems as musical objects. The rhythm of the words and the tempo of their delivery are critical to their success.

Much of the poetry is based on Sitwell’s childhood, reflecting on the things that made her happy and observations on the things that affected her deeply. She was an unwanted and unloved child and her escape lay in her imagination. Sitwell’s picture of her mother, who was prone to uncontrollable rages, has her ranting in ‘a room of the palace’ where she’s ignored.

William Walton: Façade 1 – VIII. Black Mrs. Behemoth (Edith Sitwell, speaker; English Opera Group Ensemble; Anthony Collins, cond.)

Walton’s music must also be praised. He picks up allusions and illustrates them musically, often with a touch of humour. In Jodelling Song, we hear references to other works of light classical music.

William Walton: Façade 1 – V XVII. Jodelling Song (Edith Sitwell, speaker; English Opera Group Ensemble; Anthony Collins, cond.)

The three Sitwells: Sachaverell, Edith, and Osbert

Façade was made into a ballet as early as 1929, by the German choreography Günter Hess for the German Chamber Dance Theatre. It was Frederick Ashton’s 1931 choreography, however, that proved the most popular.

After graduation from Oxford, William Walton was taken up by the three Sitwell siblings: Edith, Osbert, and Sacheverell, who provided him with a base and connections to the London cultural world. In addition to creating the musical world for Edith Sitwell’s Façade poems, Walton used Osbert’s libretto for his cantata Belshazzar’s Feast.

Façade gave him instant recognition, if not notoriety, as a modernist. Modernism, unfortunately, went out of style and Walton came to be viewed as old-fashioned and was dismissed. By the end of his life, however, his work had come back into favour. Façade has been called ‘one of the most original and startling collaborative works of art ever created in Britain,’ and stands solidly as a representative of the innovations Britain between the wars.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter