As we say goodbye to 2022 and hello to 2023, we embark once more on a journey into the unknown. We might have gained the upper hand in the seemingly never-ending struggle against Covid-19, but new flu variants are once again emerging. Senseless wars are still raging, while aggressive posturing to start new conflicts are already being made public. Yet every journey, “of a thousand miles,” as Lao Tzu, the founder of philosophical Taoism wrote, “begins with a single step.” For famed conductor Sir Simon Rattle there is “only the journey, never the destination,” but my favourite quote actually belongs to the English singer-songwriter and actor David Bowie, who suggested, “The truth is of course that there is no such thing as a journey. We are arriving and departing all at the same time.” As we are rushing towards 2023, let’s commemorate the passage of time by embarking on a couple of musical journeys.

Vincent d’Indy: Tableaux de voyage, Op. 33

Vincent D’Indy: Tableaux de voyage

During the summer of 1888, Vincent D’Indy once again spent time in Bayreuth, Germany. The impressions he brought back from his various travels in Germany and Austria are encoded in his Tableaux de Voyage, a collection of thirteen pieces for piano. As he wrote to Paul Poujaud in 1889, “I’ve just perpetrated thirteen short piano pieces – varied memories of my walks across Germany… Some of them are bad, I warn you, others are better, and there are a few good ones, which you’ll like, I hope, so I ask you to accept them as simply as they are offered to you.” Two years later, he orchestrated six of the pieces to form an orchestral suite of the same name. Both the piano and orchestral versions open with a mysterious episode simply entitled by a question mark. As an observer wrote, “It seems to be an obsessive memory of people and things from a far country, set in the midst of varied landscapes, an expression of regret, of which no contemplation can diminish the strength.”

Vincent d’Indy: Tableaux de voyage, Op. 33 (excerpts) (Jean-Pierre Armengaud, piano)

Christopher Gunning: Night Voyage

Christopher Gunning

Christopher Gunning, born on 5 August 1944, studied composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. He quickly gained a reputation for his scores for film and television dramas, including such hit TV productions as Agatha Christie’s Poirot, and the TV miniseries Rebecca. During a career spanning 50 years, he has won 4 BAFTA and 3 Ivor Novello Awards, and BASCA’s prestigious Gold Badge Award. In his retirement, however, Gunning decided to focus on writing classical works. So far, he has composed twelve symphonies, as well as concertos for the piano, violin, cello, flute, oboe, clarinet, saxophone, and guitar. His tone poem Night Voyage recounts his experiences as an owner of a small sailing yacht. As he explains, “This sea piece was born on a rainy evening standing by the Mersey River. To the West, a patch of orange lit the darkening sky, seabirds called mournfully, and I watched a large grey freighter slipping majestically out to sea. Where was it heading and what would befall it? My ship takes an imaginary journey; first there is the optimism of a new adventure, but then we meet a violent storm.”

Christopher Gunning: Night Voyage (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Christopher Gunning, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 112

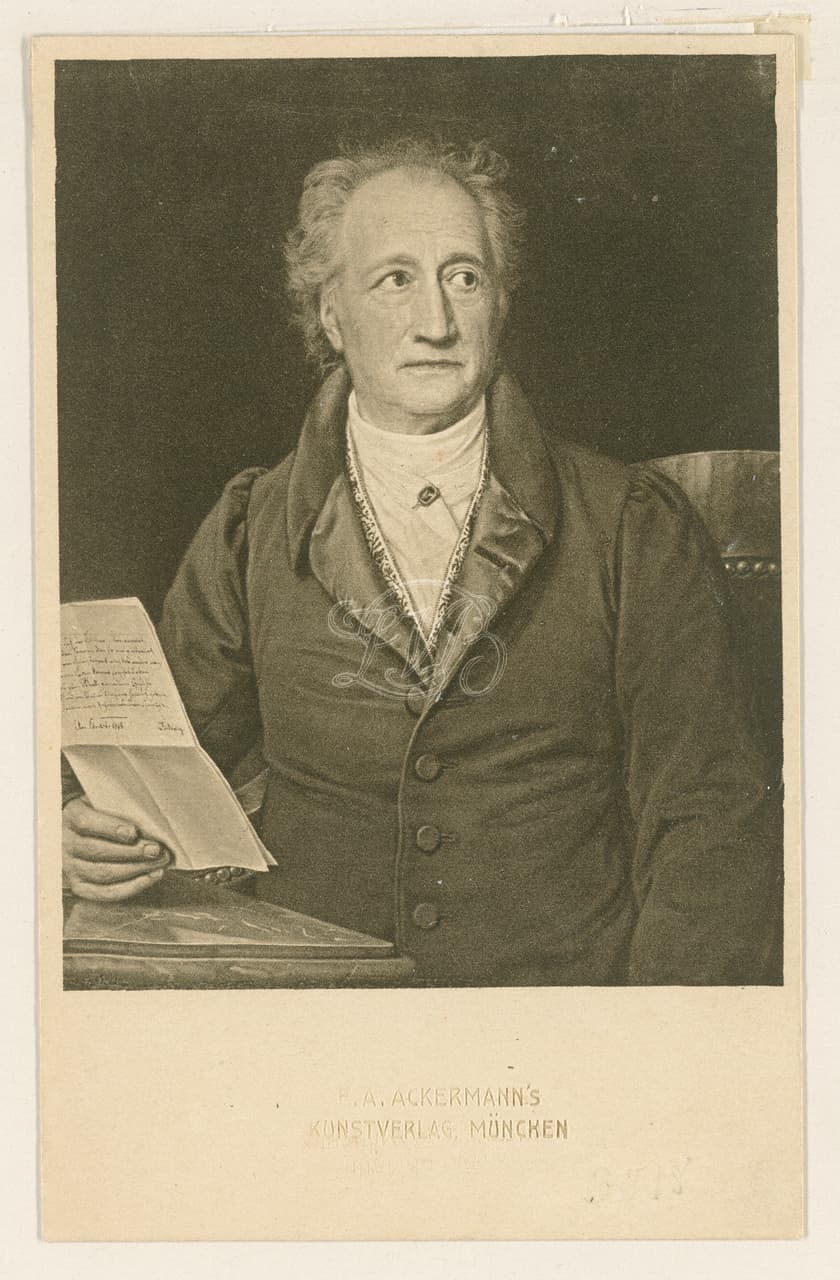

Beethoven and Goethe

During a voyage to Italy, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe took a boat ride to the island of Capri. With thunderstorm clouds forming during the journey, the ocean suddenly became ominous and eerie calm. Fortunately, the severe weather moved away, the wind returned, and the poet was able to complete his journey unharmed. It did inspire him, however, to write two poems, both dating from 1795.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

“Meeresstille” (Calm Seas)

Deep stillness rules the water

Without motion lies the sea,

And worried the sailor observes

Smooth surfaces all around.

No air from any side!

Deathly, terrible stillness!

In the immense distances

not a single wave stirs.

“Glückliche Fahrt” (Prosperous Journey)

The fog is torn,

The sky is bright,

And Aeolus releases

The fearful bindings.

The winds whisper,

The sailor begins to move.

Swiftly! Swiftly!

The waves divide,

The distance nears;

Already I see land!

For Ludwig van Beethoven, Goethe’s poem became the starting point of the cantata

Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 112, completed in 1815 and published in 1822 with a dedication to Goethe.

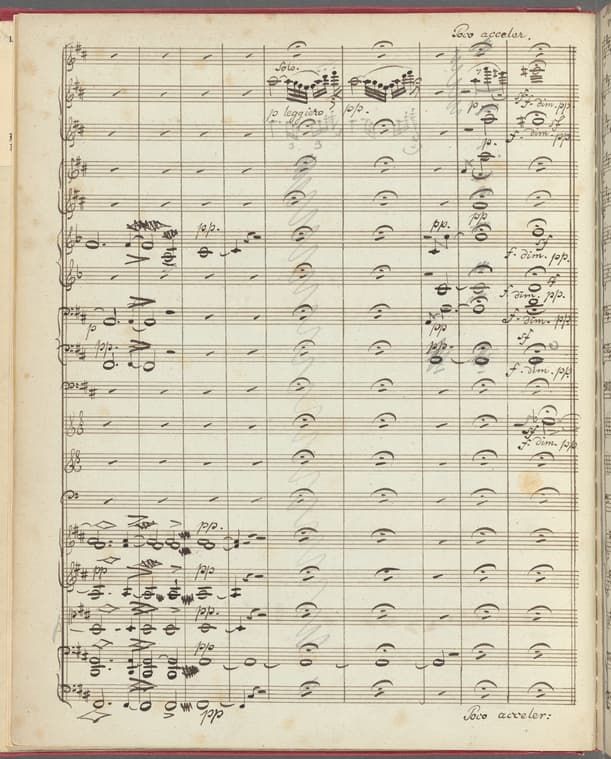

Felix Mendelssohn: Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 27

Mendelssohn’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 27

Only a couple of years after the premier of Beethoven’s cantata, Felix Mendelssohn composed a concert overture on exactly the same two poems by Goethe. Mendelssohn first met Goethe at the age of twelve when his teacher took him to meet the great poet at Weimar. He writes to his parents, “every afternoon Goethe opens the piano saying, ‘I haven’t heard you at all today, give me a little noise’; and then he will sit down beside me and when I am finished I ask for a kiss or take one. You cannot imagine his kindness and friendliness.’” Seven years later Mendelssohn embarked on his Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 27, and he verbally described his interpretation of Goethe’s calm sea as follows; “a pitch gently sustained by the strings for a long while hovers here and there and trembles, barely audible… The whole stirs sluggishly from the passage with heavy tedium. Finally, it comes to a halt with thick chords and the Prosperous Voyage sets out.” Goethe was certainly impressed, and after hearing a performance wrote to Mendelssohn “Sail well in your music, and may your voyages ever be as prosperous.”

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Les voyages de l’Amour, Op. 60

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier (1689-1755) grew up in Metz and was expected to take over the confiserie business from his father. However, supremely interested in music he escaped the life of a confectioner and followed his music teacher Joseph Valette de Montigny to Perpignan. Once he had moved on to Paris, Boismortier was granted the first license to print his own works, which jump-started a successful career as a composer and publisher. In his opéra-ballet Les Voyages de l’Amour, Op. 60, personified Love undertakes a journey across baroque France. Love is tired of having to make everybody happy while he is denied happiness. As such, he sets out in search of a pure heart that might love him sincerely and without ulterior motives. His journey takes him to villages and towns and to the royal court. In a small hamlet out in the country, he eventually comes across true love in the form of the young shepherdess Daphné, who is willing to offer her heart to love unconditionally.

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Les voyages de l’Amour, Op. 60 – Act II: “Simphonie pour l’arrivée des Génies Elémentaires” (Ensemble Meridiana)

Henri Duparc: L’invitation au voyage

Henri Duparc

In 1841, the poet Charles Baudelaire was sent on a voyage to Calcutta, India, by his stepfather. Charles had been an unruly youth, and it was hoped that the young poet would manage to get his worldly habits in order. The trip provided strong impressions of the sea, sailing, and exotic ports, which he later employed in his poetry. The sense of “oriental splendor” is a recurring theme in many Baudelaire’s poems, and his Indian voyage provided an obsession with exotic places and beautiful women. In “L’invitation au voyage” these two elements combine in one photograph, one single dream of perfect happiness. The poet invites his mistress to dream of another, exotic world, where they could live together.

Charles Baudelaire

L’invitation au Voyage

My child, my sister,

think of the sweetness

of going there to live together!

To love at leisure,

to love and to die

in a country that is the image of you!

The misty suns

of those changeable skies

have for me the same

mysterious charm

as your fickle eyes

shining through their tears.

There, all is harmony and beauty,

luxury, calm and delight.

As with much of Baudelaire’s poetry, however, the dream maintains a vague sense of nightmare. The poem progresses through a sequence of flashing images without meaning, and a cloud of symbols with no system. The refrain succeeds only in part in restoring a peaceful atmosphere: the reader already knows that it is nothing more than an illusion.

Henri Duparc: “L’invitation au voyage” (Giorgos Kanaris, baritone; Thomas Wise, piano)

Gabriel Pierné: Voyages au pays du Tendres

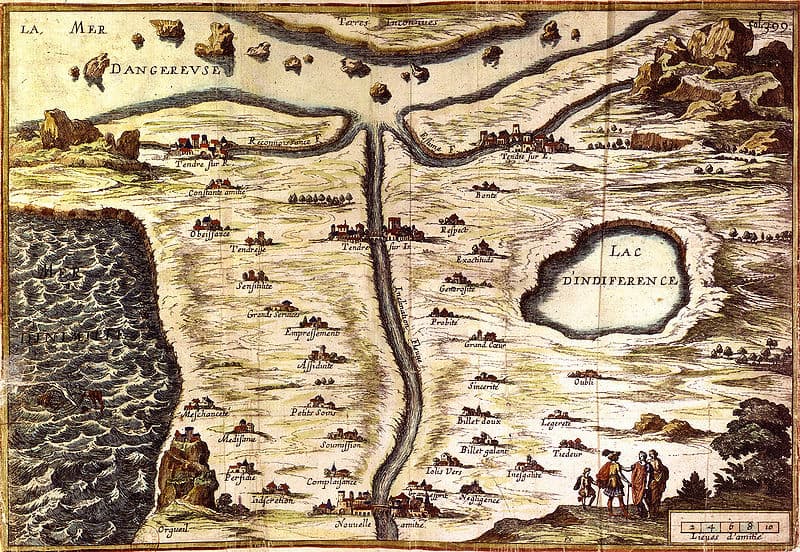

Map of Tendre

Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937) started work on Voyage au pays du Tendre (Journey to the Land of the Tender) in 1935. The work draws its inspiration from a marathon novel by “the very precious Madeleine de Scudéry (1607-1701), Clélie.” The novel contains an allegorical map of the tender sentiments, from which the composer builds a journey without thematic connections. A few harp arpeggios depict the “L’Embarquement sur le fleuve Inclination” (Embarkation on the Inclination River) whose course is drawn by a placid flute motif accompanied by the strings. The music portrays “Tendresse” (Tenderness), Empressement (Attentiveness), and Confiante Amitié (Confident Friendship). The mood darkens in Perfidie-Méchanceté (Perfidy-Spitefulness), and the listener is swept away on the “Mer d’Inimitié “(Sea of Enmity). The rejected traveller finds refuge in “Soumission” (Submission), and everything brightens near “Billets gallants” (Courtly Notes) and “Jolis vers” (Pretty Verses). The journey concludes with Billets doux (Love Letters), and “Retour par Tendre sur Inclination” (Return via Tender on Inclination) transports us back to a repeat of the beginning in a freshly discovered C Major.

Gabriel Pierné: Voyages au pays du Tendres (Carlo Jans, flute; Martinů Quartet)

Khadija Zeynalova: Journey to Love

Azerbaijan (The Land of Fire)

The name Azerbaijan, the country bordered in the north by Russia, in the west by Georgia and Armenia, in the south by Iran, and in the east by the Caspian Sea, derives from the Old Persian word “Azar,” meaning fire. Already thousands of years ago, flames fueled by its enormous oil and gas reserves, raged on the hills along the Caspian Sea. Khadija Zeynalova grew up in Azerbaijan, and studied composition, music theory, and musicology at the Academy of Music in Baku. In 2005, Zeynalova went to Germany, 4,000km away from her homeland to study at the Detmold Academy of music. “In the beginning,” she explains, “Germany was a culture shock for me. Many things were completely different here: a different culture, different people, different traditions, and a different mentality. The beginning here was not easy, especially the German language.” The often-hostile forces of nature of her homeland Azerbaijan primarily inspire her chamber music compositions. Zeynalova does not exclusively rely on tone painting in the true sense of the word, as “myths often form the background of her compositions, myths that at the same time build an obvious bridge, a Journey of Love, between the Caucasus region and Central Europe.”

Khadija Zeynalova: Journey to Love (Bridge of Sound)

Carl Nielsen: An Imaginary Journey to the Faroes, FS 123

Carl Nielsen

Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) composed the rhapsody overture An Imaginary Trip to the Faroe Islands on commission from the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen. The work was intended for two concerts at which 50 inhabitants of the Faroe Islands were supposed to perform examples of their national dancing songs. These concerts were originally scheduled to be performed in January 1927, but were postponed because of an influenza epidemic in Copenhagen. This gave Nielsen some additional time to finish the composition, which first sounded on 27 November 1927. A couple of days before the gala performance, Nielsen was interviewed to explain his compositions, and he responded, “I have used many of the Faroese melodies in it, but the introduction and ending are free compositions.” Nielsen clearly composed a sea voyage, but he did not have a particularly high opinion of the work. As he subsequently wrote to a friend, “You must not believe that I attach any importance to it; it is an occasional piece and nothing more than a piece of jobbery on my part.”

Carl Nielsen: An Imaginary Journey to the Faroes, FS 123 (Scottish National Orchestra; Alexander Gibson, cond.)

Jacques Offenbach: Le voyage dans la lune, “Overture”

First Story of the Trip to the Moon by Jules Verne

As we are rocketing towards 2023, let’s conclude with a journey to the moon, at least as it was imagined by Jules Verne and Jacques Offenbach. The popular French novelist, poet, and playwright Jules Verne published his novel From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 minutes, in 1865. You may also know some of his other bestselling adventure novels include Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1872). Always ready to take the technological advances of the time into consideration, Verne tells the story of a society of weapons enthusiasts, and their attempt to build an enormous space gun to launch three people in a projectile toward the Moon. Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) completed his opéra-féerie in four acts and 23 scenes titled “Le voyage dans la Lune” in 1875. Apparently, Offenbach did not inform Jules Verne, who complained about its similarities to his work. If there was an open dispute, it seems to have been settled amicably. Critics view the work as a “demonstration of Offenbach’s flair for topicality, mixing science and fairy-tales, and building modern Utopias into the traditional framework of the pantomime.” And mind you, Offenbach found an entire population of Moon-dwellers, ruled by Cosmos, king of the Moon. Let’s hope that our journey into 2023 will be just as rewarding.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

What about Liszt’s many Years of Pilgrimage?

And what about RVW’s Songs of Travel?