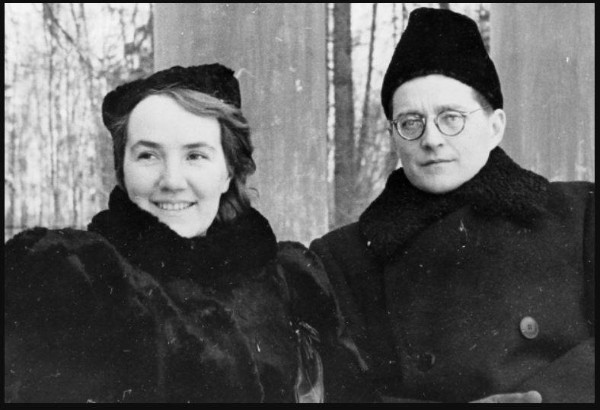

Alessandro Moreschi at age 20

However, cast your mind back to the 18th century – at that time, the castrato was the singer of the day. These were men who had particularly good voices as children and who were castrated before they reached puberty when their voices changed. They were often favored as lovers because they were demonstrably “safe.”

The lack of testosterone meant that castrato singers often were very tall with great lung capacity. Although we now make analogies with castratos sounding like sopranos, their greater lung capacity turned them into virtual singing machines – they could sing louder and longer than any soprano of the day.

Castrato operations were outlawed in the 1860s in Italy and there is only one extant recording of a castrato. Alessandro Moreschi (1858 – 1922). He was recorded in 1902 and 1904, when he was in his mid-forties, and, to our ears, these recordings are often a puzzle. It is thought that he suffered castration as a cure for a hernia when he was about 12. He was a talented singer and sent to Rome where he became First Soprano of the Sistine Chapel Choir, a post he held for 30 years.

Alessandro Moreschi sings Ave Maria

When Moreschi joined the Sistine Chapel Choir, he joined six other castrato singers. But the others were no longer able to sing the high soprano line in one of the most famous works written for the Chapel, Allegri’s Miserere, and so Moreschi came into his own. The director of the Sistine Choir was once a castrato soprano and he saw in Moreschi a way to preserve their famed performances of the work.

Sistine Chapel

It took the 14-year-old Mozart, visiting the Sistine Chapel during Holy Week who heard the work on Holy Wednesday, went home and transcribed it from memory, and then returned on Holy Friday to check his transcription, to bring this piece out of hiding. He gave the transcription to the historian Charles Burney and it was published in London in 1771. After this, the ban from the Vatican was lifted.

Allegri: Il salmo Miserere mei Deus (Tallis Scholars; Peter Phillips, cond.)

When Pope Pius X took the throne in 1903, he outlawed castrati from the choir and they were replaced by boy’s voices. Today, the top soprano line is performed by a young boy with an unchanged voice. They can get the height of the line, but their voices remain quite thin.

Now, try to combine the 1902 sound with the Tallis Scholars recording – think of that high soprano line being produced by a powerful voice and ringing through the Sistine Chapel. There’s a reason that the work held listeners’ imaginations for centuries and what we hear now is only a slight echo of what it once was.