Protesters across the United States have taken to the streets in the wake of George Floyd’s death demanding an end to police brutality and systemic racism. And as the international human rights movement “Black Lives Matter,” that protest has resonated across the globe. Black composers have always suffered from societal prejudices, with composer T.J. Anderson declaring, “we’ve been invisible.” Some of the factors for this exclusion, however, are specific to the world of classical music. Black composers have “been criticized in both African-American and white intellectual circles for refusing to embrace mainstream commercial trends,” ostensibly turning all black composers into members of the avant-garde.

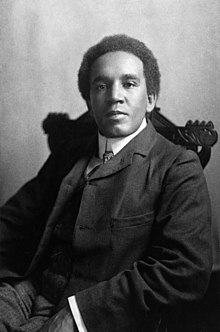

William Grant Still

William Grant Still

Yet, there was a time in classical music when black composers were at the cusp of floating with the mainstream. One of the pioneers, William Grant Still (1895-1978), described as the “Dean of African-American composer,” wrote almost 200 works in a wide variety of genres: all inspired by spirituals, African-American work songs, ragtime, blues and jazz. His best-known work, the Afro-American Symphony composed in 1930, received performances by the Berlin Philharmonic, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra and the BBC Orchestra, respectively. Still writes, “I knew I wanted to compose a symphony, I knew that it had to be an American work; and I wanted to demonstrate how the blues, so often considered a lowly expression, could be elevated to the highest musical level.”

William Grant Still: Symphony No. 1 “Afro-American” (Cincinnati Philharmonia Orchestra; Jindong Cai, cond.)

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Like a good many other geniuses, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) died way too young. He succumbed to a lung infection at the age of 37, but despite his short life was able to leave behind an astonishingly comprehensive range of compositions. He was born in London, the result of an affair between Dr. Daniel Hughes Taylor—a doctor from Sierra Leone—and the English woman Alice Hare Martin. Dr. Taylor returned to Africa and Samuel grew up supported by his mother alone. The little boy had a startling natural aptitude for the violin, and by the age of fifteen he was accepted into the Royal College of Music. During his five years of study he attended the composition classes of Charles V. Stanford, who considered him “one of his two most brilliant students.” Coleridge-Taylor possessed both prodigious talent and refined musical taste, which quickly emerged in a number of significant chamber music compositons. In a whole series of works like the African Suite Op. 35 or the 24 Negro Melodies Op. 59, Coleridge-Taylor consciously and proudly processed his African heritage. But his greatest claim to fame is his three-part cycle of cantatas inspired by Henry W. Longfellow’s Indian epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha.” He personally traveled to the United States on three different occasions to conduct his cantata, and in 1904 was received by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: African Suite, Op. 35, “Danse nègre” (London Symphony Orchestra; Paul Freeman, cond.)

Florence Price

Florence Price

At the height of her career, Florence Price (1887-1953) tried to convince Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra to program her music. “To begin with,” she wrote in a 1943 letter, “I have two handicaps — those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins. I should like to be judged on merit alone.” Her plea was not successful then as now, as the Boston Symphony still hasn’t played a note of her music. As a composer, none come more impressive than Florence Price. She was the first black woman to have a work performed by a major symphony orchestra. In 1933, her first symphony premiered with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and a music critic declared it, “a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion… worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertoire.” Price grew up in the Jim Crow South, but after moving to Chicago she began to publish her music and quickly gained national recognition. Aided by Langston Hughes and Marian Anderson, Price became a prominent figure in the world of music.

Florence Price: Symphony No. 1 in E minor (Fort Smith Symphony; John Jeter, cond.)

George Walker

George Walker

In 1996, George Walker (1922-2018) became the first living African-American composer to win the Pulitzer Prize. He received the award for his Lilacs, premiered by the soprano Faye Robinson and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Seiji Ozawa. As a composer and performer, Walker always had the most impressive resume. He entered Oberlin Conservatory at age 15, and subsequently became the first African American to attend the Curtis Institute of Music. He studied piano with Rudolf Serkin and Mieczyslaw Horszowski, and chamber music with Gregor Piatigorsky and William Primrose. Advanced studies at the Eastman School of music led to Walker becoming a private student of Nadia Boulanger. His probably best-known work is the Lyric for Strings, written as a memorial to his grandmother. Walker is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and became the first living composer/pianist to be inducted into the American Classical Music Hall of Fame in 2000.

The compositions of all four featured black composers—and numerous others—are woefully underrepresented in today’s concert halls. Yet, as conductor Leonard Slatkin once suggested, “no single program or event dedicated to black composers is more important for fostering diversity than a broader emphasis on arts and education.”

ALL composers matter, just as ALL lives matter!

I love the music of Grant Still. Years ago the conductor Charles Floyd ( who conducted the orchestra during the inauguration of Obama) introduced his music to the orchestra Holland Symfonia in Amsterdam . They played his Afro American Symphony . Great music.

Later I discovered his Wailing Woman which is even more impressive .

Thank you, thank you, thank you for this information about black composers! I had the privilege of hearing George Walker in recital 20 years ago in Grand Rapids, MI. His encore was a stunning interpretation of the short and popular Brahms Waltz in A-flat. As a lifetime male member of the “white privilege” club, I am proclaiming to the world that Black Lives Matter!!