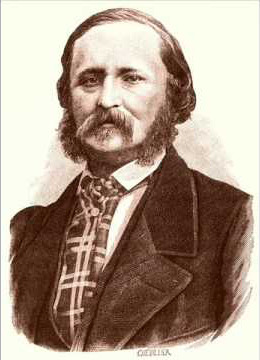

Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville

It was not the great Thomas Edison who invented the phonographs, nor Emile Berliner whose gramophone became so popular that the name was synonymous with records for nearly a century. Instead, the earliest recordings as we know today, ‘phonoautographs’, were made in 1860 by a — comparatively speaking — little known French inventor, Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville of Paris.

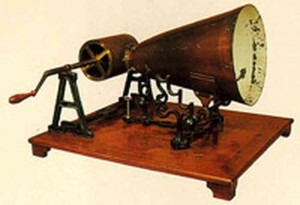

These experimental phonoautographs were made on a rather interesting medium: lines were scratched by a needle connected to a diaphragm (which would respond to the vibration of sound wave) on a piece of paper covered in soot! However, the invention did not include a working system for playback and, as a result, did not become a commercial product. The records cannot be played using a gramophone stylus or a magnetic reader; moreover, the paper was fragile. As such they had remained in silence until a few years ago. Under the First Sound project, some of the experimental recordings were successfully reconstructed in 2008 by scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California who imaged the paper, digitally removed the defects and damages, and then used computer technology to simulate the vibration using a ‘virtual stylus’ and reproduce the sound that was recorded some 150 years ago.

This sound recording of Au Clair de la Lune was actually not Scott de Martinville’s first attempt, but rather the first recognisable one upon playback. One crucial feature that enabled the successful playback was his introduction of the recording of a tuning fork’s signal in parallel for measuring the pitch. In those days, recording machines were hand-cranked, which resulted in a rotating speed that was not uniform. Without a reference, the speed variation cannot be corrected, and the even earlier recordings that he made between 1853 and 1860 are therefore not playable in recognisable forms.

While recordings in the 19th century were mostly experimental, the technology matured during the 20th century; and gramophones, cassette tapes, CD’s, mp3 etc. all became highly successful commercial products. People can now enjoy world class performances in their living room or even on the road, and this convenience brought about some paradigm shifts. For instance, the scarcity of a full size orchestra no longer limits the availability of orchestral music and recordings have, consequently, effectively eliminated transcribed music written to popularize symphonies from recital repertoires. On the other hand, recording technology must have helped general music education by making master pieces played by leading musicians available to anyone who gets hold of a copy.

While recordings in the 19th century were mostly experimental, the technology matured during the 20th century; and gramophones, cassette tapes, CD’s, mp3 etc. all became highly successful commercial products. People can now enjoy world class performances in their living room or even on the road, and this convenience brought about some paradigm shifts. For instance, the scarcity of a full size orchestra no longer limits the availability of orchestral music and recordings have, consequently, effectively eliminated transcribed music written to popularize symphonies from recital repertoires. On the other hand, recording technology must have helped general music education by making master pieces played by leading musicians available to anyone who gets hold of a copy. The way musicians and the audience would approach a performance has also been irreversibly changed. In popular music, ‘dubbing’ allows musicians to sing over their own voice which is not possible in a live performance. In the classical music arena, it is common to have wrong notes corrected and hall effects enhanced, alongside many other ‘fixes’, but note-perfect recordings made by extensive re-takes or editing sometimes do come at the expense of musicality.

The new technology has nevertheless given life to some interesting recording projects otherwise impossible such as time-compressed music (playing back long pieces of music in a second), Yo-Yo Ma’s ‘duet’ with Piazzolla (after the latter’s death, using studio outtakes), the Catcerto (piano concerto with a cat as the soloist), and many other.

According to Scott de Martinville, one of his motivations was ‘to record sound by a process similar to the recording of light by photography’, which had first been made a few decades earlier. Indeed, recording technology has, as photography, come a long way since: it literally established an entire engineering industry and contributed substantially to modern art, entertainment, and mass media. In addition, it is, above all, a big business whose annual revenue is far greater than its humble beginning on paper covered in soot might suggest.