Beethoven is famous for writing big, loud, boundary-breaking music, from the string-breaking fury of his late piano sonatas to the glorious dramatics of his ninth symphony for chorus and orchestra.

But the heart and soul of Beethoven’s art are found in his divine slow movements. Today we’re looking at six of his most heavenly adagios, larghettos, and allegrettos.

Piano Concerto No. 5 (“Emperor”), Movement 2 (1809)

Julius Schmid: Beethoven’s Walk in Nature

Beethoven’s fifth piano concerto was written in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars. The year was 1809, and 38-year-old Beethoven was living in Vienna, making his living as a freelance musician. France was invading the Austrian capital, and wartime conditions were proving unbearable for a man already suffering from tinnitus. “Nothing but drums, cannons, men, misery of all sorts,” he reported in a letter to his publisher. At one point he ensconced himself in his brother’s cellar, pressing pillows to his head to keep out the noise.

During the tumult, he wrote what became known as his “Emperor” piano concerto (a nickname, by the way, that he never assigned to the work, and, given his bitter disappointment with Napoleon’s autocratic ambitions, probably would have hated). It was premiered in 1811. All three movements are memorable, but there’s something about the heartbreaking sincerity of the slow movement that makes it especially unforgettable, especially given the dramatic circumstances in which it was composed.

Violin Concerto, Movement 2 (1806)

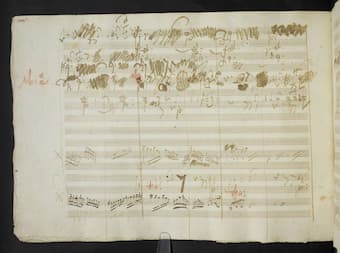

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto corrections

In 1806, Beethoven wrote a grand violin concerto for his friend, violinist Franz Clement, in part due to the feedback he’d given Beethoven about his opera Fidelio. But by the time of the premiere, Beethoven’s gift ultimately turned into a bit of a nightmare: he delivered the score so late that Clement was forced to sight-read major portions of it.

Nowadays, the violin concerto is considered one of the most difficult concertos in the repertoire. It is extremely exposed, eschews flashiness, and requires superhuman intonation and bow control to play well. So it’s no surprise that a blindsided, sight-reading Clement didn’t win the audience over. The concerto only entered the repertoire in 1844, when a twelve-year-old violin prodigy named Joseph Joachim and his mentor, conductor Felix Mendelssohn, performed it to great acclaim in London.

The slow movement’s elegance, simplicity, and sense of sheer inevitability mark it out as one of Beethoven’s most exquisite.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 – II. Larghetto (Gil Shaham, violin; The Knights; Eric Jacobsen, cond.)

Piano Sonata No. 8 (“Pathétique”), Movement 2 (1799)

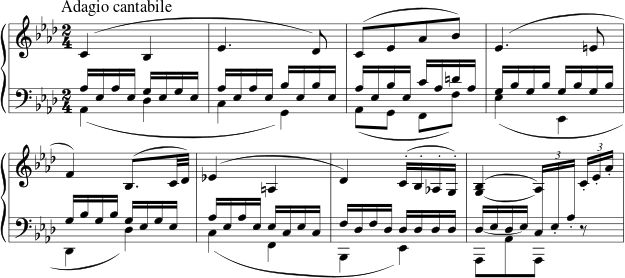

Opening of Beethoven’s Pathetique, 2nd movement

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8 was composed in 1799 and dedicated to his friend Prince Lichnowsky. Its slow movement is the work’s crown jewel. It begins with a simple, beautiful melody, accompanied by a steady flow of sixteenth notes in the other fingers. (Calibrating the balance of voices in this movement is its primary technical challenge.) The center section provides a stormy contrast before the pianist launches back into the original main theme, this time accompanied by triplets that create the feeling of a swinging motion.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13, “Pathétique” – II. Adagio cantabile (Alfred Brendel, piano)

Piano Sonata No. 14 (“Moonlight”), Movement 1 (1801)

Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata © BBC Music Magazine

Beethoven did not call the Moonlight Sonata the “Moonlight Sonata.” That nickname actually arose years later, when German writer Ludwig Rellstab wrote about the sonata in a short story: “The lake reposes in twilit moon-shimmer, muffled waves strike the dark shore; gloomy wooded mountains rise and close off the holy place from the world; ghostly swans glide with whispering rustles on the tide, and an Aeolian harp sends down mysterious tones of lovelorn yearning from the ruins.” (How evocative!) For his part, during his life, Beethoven was irritated at how popular this sonata was. “Surely I’ve written better things,” he mused to his pupil Carl Czerny.

It’s easy to see why the work resonated so strongly. From the very first hypnotic measure, it doesn’t follow the standardized sonata outline, opting instead to open with a movement that many musicians have referred to as a dirge. Beethoven’s determination to defy the conventions of the genre contributes to it sounding like a fantasia or even an outright improvisation.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2 “Moonlight” – I. Adagio sostenuto (Evgeny Kissin, piano)

Symphony No. 7, Movement 2 (1811-12)

When he premiered his seventh symphony in 1813, a satisfied Beethoven called this one of his best works. The audience agreed: they loved this slow movement so much (marked “allegretto” in the score) that they insisted on hearing it as an encore.

There’s something simultaneously so noble and beguiling about the repeating rhythmic patterns of this movement, which lend the music a dancelike quality. At the same time, the instrumental lines weave together and in and out of the texture, creating an atmosphere of ever-evolving mystery.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 – II. Allegretto (Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Herbert von Karajan, cond.)

String Quartet No. 15, Movement 3

(“Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart”) (1825)

Beethoven Monument at Beethovenplatz, Vienna

We’ll end with Beethoven’s most deeply personal adagio, the third movement from the String Quartet No. 15. It was composed in 1825 after a long period of illness that Beethoven feared would be fatal. Unusually, he gave the movement a title. Translated from German, it reads “Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity, in the Lydian mode.”

The movement is the quartet’s literal centerpiece, resting in the middle of five movements. It lasts for a very long time by Beethovenian chamber music standards – between fifteen and twenty minutes – which gives it a real feeling of weight and importance within the wider context of the full piece.

The quartet was premiered in late 1825. By the spring of 1827, Beethoven was terminally ill, and he would pass away in March of that year. This was one of the last pieces he ever wrote – and it’s one of his best.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 15 in A Minor, Op. 132 – III. Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenden an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart: Molto adagio – Neue Kraftfuhtend: Andante – Molto adagio (Emerson String Quartet)

I used the second movement of the Seventh Symphony as a theme for my radio program of book readings when I read the Death of Sherlock Homes.