Although we generally associate the symphonic poem with Liszt and mainly German composers, it also popped up in other countries, one of the most interesting being Mexico.

Silvestre Revueltas (1899–1940) had a distinguished career as a conductor, principally as assistant conductor under Carlos Chávez with the Orquesta Sinfónica de México from 1929 to 1936. He and Chávez created a place for music by Mexican composers to flourish. Starting in 1930, Revueltas started a run of symphonic poems that were fundamental contributions to the definition of the ‘national Mexican symphonic poem’, with works that were not only technical masterpieces but also original and with a fresh outlook.

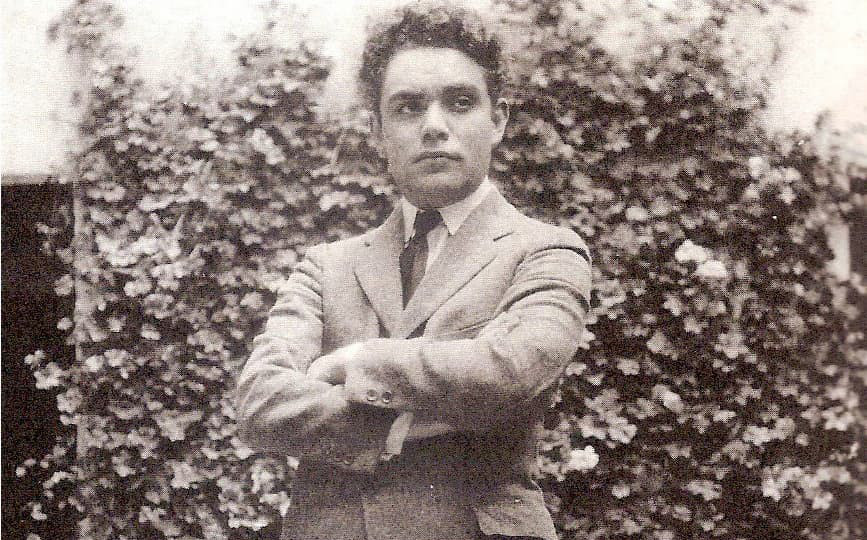

Silvestre Revueltas, 1924

These works included Cuauhnáhuac (1931), Esquinas (Corners) (1931), Ventanas (Windows) (1931), Colorines (Coloured Beads) (1932), Janitzio (1933), Caminos (Roads) (1934), Itinerarios (Routes) (1938), and Sensemayá (1938). These works can also be considered great national musical landscapes.

Sensemayá was begun in 1937 and completed in 1938, inspired by a poem by the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén. The poem is about the ritual chant performed while killing a snake, and the chant can be traced back to Africa. In Guillén’s poem, a magician transforms Princess Lucero into a snake after she refused him. Men hunt the snake, and it is the wizard himself who kills it. When the snake dies, the transformation is broken – Lucero gets her soul back, and it is the wizard who perishes.

The first version, dated May 1937, was for chorus and a small orchestra. By March 1938, this had been transformed into a work for full orchestra. The percussion section is augmented by a number of wooden percussion instruments, including claves, raspadors, gourds, and maracas. Several different sizes of drums, from ‘small Indian drum’, two sizes of tom-toms, and a bass drum, are also called for. The work is in 7/8 time, split within the measure as 2/4 + 3/8. It starts in the lowest registers: bass clarinet, then bassoon, then tuba. The low pitch, combined with the uneven tempo, is immediately unsettling.

Silvestre Revueltas: Sensemayá (Aguascalientes Symphony Orchestra; Enrique Barrios, cond.)

In the original poem by Guillén, the sense of rhythm is critical to the poem. This is a poem to be recited aloud, not read quietly:

Sensemayá – Recitado por Nicolás Guillén

Although Revueltas’ symphonic poem comes from literature, as did much of Liszt’s, this isn’t the symphonic poem of Europe: this is a New World artifact. The initial 7/8 time signature is disturbed over the course of the piece, with upbeats shifting the time off even more and leaving the listener vainly searching for a continuous beat despite the drums. The time signature also changes from 9/8 to 5/8 back to a single measure of 9/8 and returns to 7/8 at the end.

The work is considered Revueltas’ greatest work and brings a new definition and depth to what we think of as a symphonic poem.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter