Concert in Treowen Manor

The titles in italics throughout refer to pieces by Claude Debussy.

‘Valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige’ (‘Melancholy waltz and languorous vertigo’)

(Charles Baudelaire, Harmonie du Soir)

From my seat on the grassy terrace outside Treowen Manor in the Wye, I can see for miles. Skimming swallows keep me company on their evening forays; sheep have woken from their daytime torpor and graze quietly on boundless hillsides. The ponds at the edge of the wood below the house seem unusually deep tonight. Listen! Listen! Ondine, the water sprite is here. Above me the ancient, leaded windows are pushed wide and regretful Brahms confesses his sorrows from the old Broadwood. The students are busy, I am forty-five, and two summers ago I was married in that room. My Wye Valley Chamber Music Festival has been alive for twenty-one years.

At the piano in Treowen

‘Sounds and scents turn in the evening air’

Far away in Southwest France, set in the side of a verdant hill and presiding over acres of farmland, is a chateau called Ladevie. Music has long since left its walls, but thirty years ago, down on its luck, music was about to bring the magnificent old stone building back to life and in turn, that charismatic, rickety chateau was about to bring me to life. For I am not really sitting beneath the walls of Treowen at all; I am outside the old barn at Ladevie, eavesdropping on a performance of Debussy’s first book of Préludes, given by Paul Roberts. At this point, I don’t know much about Paul, but he will go on to become my teacher, still the most important person in my musical journey to date. I am eighteen and life is about the piano.

Students at summer school at Treowen Manor

The great hall at Treowen is our barn: the perfect place for intimate music-making with a crackling atmosphere and sometimes a log fire to match. These days our kids pack the enormous window ledges when we run out of seats. Many of my most magical musical experiences have taken place in that room with musicians crammed in amongst our unusually discerning audience on ascetic wooden chairs. The air in the hall is about as full of music as a room can be, but there is no competition, no ego – or at least when those two strangers arrive they are quickly persuaded to leave. The wise old chateau shares this attitude to life’s (and music’s) trinkets: embellishments are not required. I bask on the terrace in the comforting evening heat that has been baked into the earth and talk to Ann of her life as a doctor or listen to J-P’s ballades.

The crickets hum and trees sway with the stately procession of the Dancers of Delphi. I lie back and stare up at the characteristic Quercy-style roof of the pigeonnier, rolling the stem of my glass between my fingers. Sails and Veils billow their way across the lawn. Down amongst the endless fields of sunflower and lavender, the wind on the plain is biding its time. I peer through the door at the rows of rapt audience beneath the knowing wooden beams and watch Paul coax his old Steinway to life. Next is my favourite – Sounds and scents… This barn and chateau have been here forever and I, too, have somehow been here before, just waiting for the right time to come back. Debussy has visited this place. The sounds, the scents, the wood and the stone are one, the core of a ripe authenticity never tasted before.

Treowen Manor

In a happily functional room in Birmingham, I work with my student on Liszt’s own Harmonies du Soir. I can see myself in her restless, probing questions and curious, personal and musical intensity. A feeling of despair resonates in my stomach like a silent gong; how can I show her Ladevie and reveal what it all means? But as I sit down and breathe the air, touch the keys, I am reassured that at least a few stones of the old place are safe inside me. I look at Paul’s papercut bloodstain on my copy of Ravel’s Valses Nobles et Sentimentales and the pages where an ember from one of my teenage roll-ups fell.

Ladevie was the place where piano became music, and where music became everything. Arriving from provincial Somerset with my brother Joe, we drank bitter coffee from cracked bowls and black Cahors wine from tumblers. I tasted food with a new vividness and made friends for life. Young, ambitious students shared classes and the dinner table with passionate adult amateurs and all were intoxicated by music as the juice dripped from the fat peaches or the crust of the morning baguette cracked in the hands. Paul read to us, invoking Verlaine and Baudelaire, and there were many wonderful musical moments, but his performance of the Préludes (Book I) stays inside me. Place and music were perfectly synthesised, in a manner as profound and perfect as the ocean depths of La Mer or the dazzling sunshine of The hills of Anacapri. Music was no longer just a part of life; now all of life welled up inside the music itself. This was original sin, the nascent moment that would guide all future music-making.

Ladevie through the sunflower fields

It was more than simply an exotic experience of French music in France, although of course there is something deliciously genuine about sitting under the same stars and tasting the same wine as the composers and poets with whom you are drawing your inspiration. The experience transcended a teenage rite of passage, despite our tender age and readiness; I sensed this because I have known the feeling since (and of course before). Until this point, my life of piano festivals and competitions had not yet met a tangibly supportive audience or family of colleagues; I had received my share of compliments, but was often playing to win. How miraculous, then, to listen to Spencer playing Rhapsody in Blue or Steve playing Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata and suck the marrow from the music through, and with them. This communal spirit has often since proved elusive, even at Prussia Cove in Cornwall, apparently the inspiration for the course at Ladevie. The barn was a perfect space for intimate music-making, where Paul’s grudging old Steinway eventually yielded up its perfect, bell-like sounds.

Musicians must be master manipulators of time; we begin each performance with a knowledge of the end, simultaneously piecing together our interpretations as linear narrative, mosaic and cyclic structure. Furthermore, all music converses with other music, deriving its delicious multiplicity of meanings (in the absence of words) from an almost infinite and constantly shifting web of intertexts. After all, who is Beethoven without Haydn, Bach or Bernstein? Or Debussy without Liszt and Rameau? In a Birmingham coaching we notice how a passage in a Dvořák piano trio simultaneously allows us to experience time from all three possible vantage points, a nostalgic violin melody looking back, urgent inner parts imbuing palpable, present excitement and the piano’s bass drawing the music inexorably forward into a future return to the opening material. Musicians know that memories can be yet to come and that we can look forward to a return to the past. Why might not this wisdom apply equally to place? When I performed the first book of Debussy’s Préludes in my final graduate recital in the utilitarian concert hall of the Guildhall School, those attending carefully would have heard the slow crescendo of the crickets and smelt the sultry perfume of the barn and terrace. My most treasured musical compliment came when a friend commented that my performance at London’s Wigmore Hall was ‘just like being at Treowen’. In saying this, of course, my friend recalled the occasion on which Paul played Debussy at Ladevie – even though he wasn’t there.

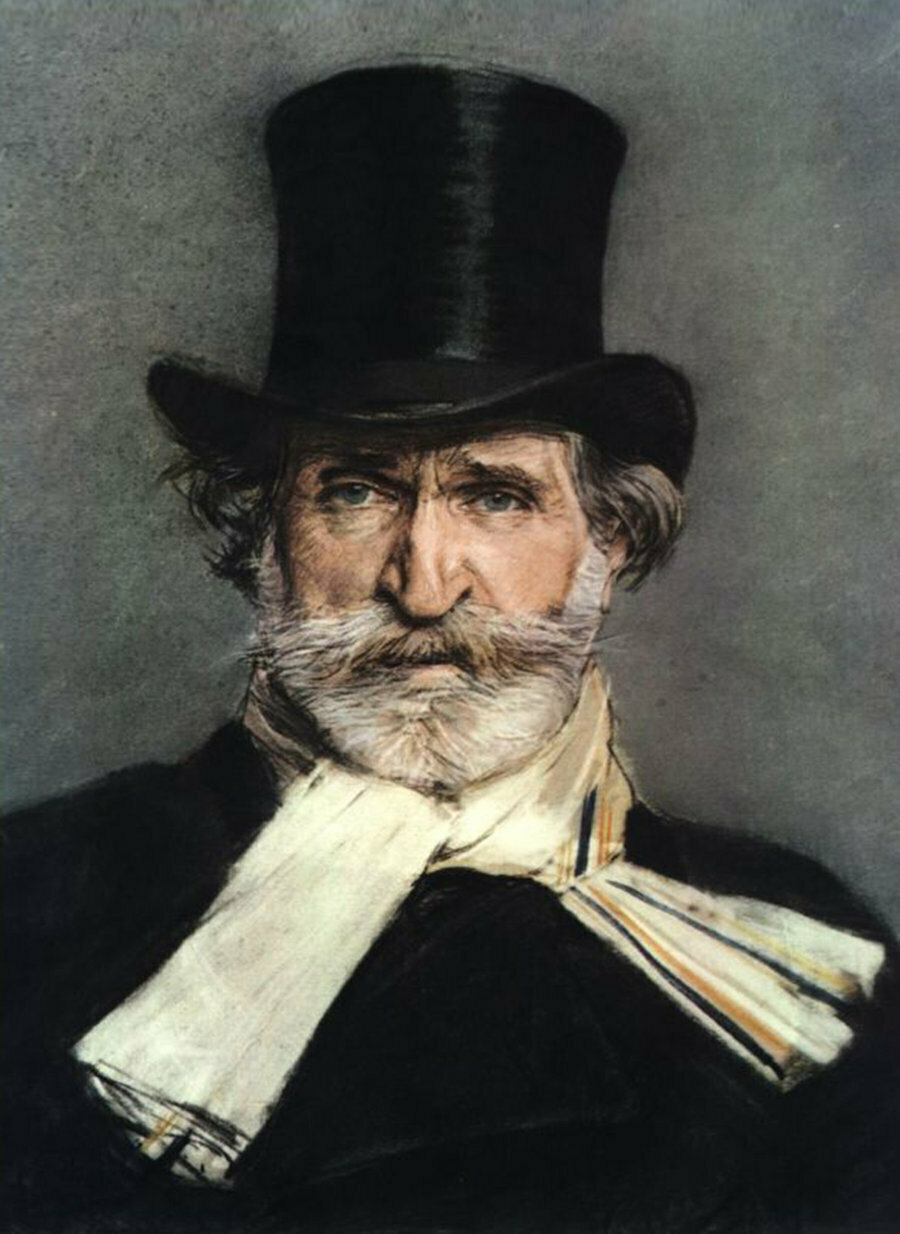

Paul Roberts

Chamber music was revealed to me as the ideal embodiment of this kind of intense, sincere music-making where heart and head are both integral to a living musical organism. I rushed off with a little band of like-minded souls and set up a festival in the Wye Valley amongst winter snows and log fires. Ladevie was not only for the summer, after all. I found a place where memories were not only in the past and in which a future could be made. I didn’t meet Sara, my wonderful, literary wife, until I was nearing my fourtieth birthday.

Now she enters the long drawing room at Treowen in her bridal dress and my heart dances. She walks slowly towards me as Joe plays Strauss’s Morgen! at the Broadwood: ‘and tomorrow the sun will shine again’. She does not know it, perhaps until now, but she has joined me at Ladevie. Life is perfect, full of juice and promise.

‘Resounding through all the notes,

In the earth’s colourful dream,

There sounds a faint long-drawn note,

For the one who listens in secret.’

(Friedrich Schlegel. Printed at the head of Robert Schumann’s Fantasy in C, Op. 17, for Clara Wieck)

Daniel Tong is a pianist and teacher, founder of the Wye Valley Chamber Music Festival, pianist of the London Bridge Trio and Head of Piano in Chamber Music at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire.

www.danieltong.com

Paul Roberts continues his summer course in France each year, now Music at Chateau d’Aix.

www.PaulRobertsPiano.com

www.musicauchateau.com

Dear Daniel

I`ve enjoyed reading about Ladevie, I was Head of Woodwind at Birmingham Conservatoire from 1993 -1998 and loved every minute of it

Ladevie is important for me, I remember looking for various piano courses for a friend in Manchester– Ann Braine ,a distinguished surgeon and fine amateur pianist, I recommended her to go to Ladevie

She fell in love with the place and bought a house nearby, (she now runs her own course and series in the Lot) we went down to stay with her and loved the area, so in 2000 we bought a house near Ladevie and often go past it now !

All best wishes

Janet

Hi Janet

Many thanks for your comments. I know Ann Brain and stayed in her houses in the Lot several times. I think maybe I even refer to her in the piece above.

Long may music-making continue in this wonderful area of the world.

Best wishes

Daniel

Wow! Dan Tong! I was there in Ladevie in the same course as you almost three decades ago. I remember you played the Ravel Valses nobles et sentimentales and also Scriabin Two Poemes (which I was inspired to learn). Sounds like you’re doing well. How is Joe? Good times.