“The purpose of music is to communicate from the heart to the heart”

Leon Fleisher, 1963

He has been called “one of the most refined and transcendent musicians the United States has ever produced.” But Leon Fleisher (1928-2020), who died of cancer at the age of 92, is bigger than that. At the height of his initial pianistic career, Fleisher was mysteriously struck by a horrifying disability in his right hand, with the fourth and fifth fingers becoming unresponsive and uncontrollable. His purpose in life alongside an incredible performing facility—something he had naturally taken for granted—was taken away in an instant.

For a time he even considered suicide, but after two years of despair and trying every available medical treatment known to humanity, Fleisher realized that he needed to look in different directions. “I suddenly came to the realization that my connection with music was greater than just as a two-handed piano player,” he said. He spent a good deal of time on teaching, and even began a career as a conductor. But what is more, he began to probe and discover the left-hand repertoire specifically composed for and commissioned by the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm during World War I. Having finally accepted his condition, Fleisher never gave up hope, and after deep tissue manipulations and an extended course of Botox injections, he resumed his career with ten fingers in 1996. In times of the Covid-19 Pandemic, Fleisher’s determination to overcome adversity and finding different ways of expressing himself is a powerful lesson for all ages.

Leon Fleisher grew up in San Francisco, son of a poor Jewish immigrant family, with his father hailing from Odessa and his mother from Poland. His significant talent became obvious early on, and by the age of four he started formal piano lessons with Gunnar Johansen, Lev Schorr, and Ludwig Altman. He made his first public appearance in San Francisco at the age of eight, and the following year was accepted for study with the legendary Artur Schnabel. At sixteen, he performed the Brahms D-minor concerto with the New York Philharmonic under Pierre Monteux, who called him “the pianistic find of the century.

Fleisher receiving the Kennedy Center Honors alongside Steve Martin, Diana Ross, Martin Scorcese and Brian Wilson in 2007

Fleisher signed an exclusive recording contract with Columbia Masterworks in the 1950s, and he gave acclaimed performances on both sides of the Atlantic. He was described as a pianist who had it all, “a technique that knew no difficulties, a bejeweled and expressive tone, a sure intellectual command of musical form, and an acute sensitivity to whatever he played.” He also became a faculty member at the Peabody Conservatory, writing in his memoirs “there was always more to attain, and more to achieve, and more musical depths to plumb, and lurking behind it all, the terrifying risk of failure.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4, Op. 58 (Leon Fleisher, piano; Cleveland Orchestra; George Szell, cond.)

Leon Fleisher and Gary Graffman in Hong Kong, 2004 © Georg Predota

In 1965, Fleisher was scheduled to tour the Soviet Union with conductor George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. Suddenly unable to control the fourth and fifth fingers of his right hand, Fleisher had to cancel his appearances and mystified, began to search for a cure. He tried all available treatments, including acupuncture, hypnosis, Zen Buddhism, carpal tunnel surgery and intensive self-help programs and seminar. Initially nothing worked, and the condition was eventually diagnosed as Focal Dystonia, a neurological condition that affects a group of muscles in a specific part of the body. In musicians, it most commonly involves muscular contractions, with the fingers either curling into the palm or extending outward without control. Fleisher recalled, “The gods know how they hurl their thunderbolts. Having spent 36, 37 years of playing two hands and then to have it denied was a tremendous blow.” The same condition also affected his good friend and colleague Gary Graffman, and both turned to the left-hand repertory commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein. And that included dedicated concerti and chamber music works by Ravel, Prokofiev, Richard Strauss, Korngold, Britten and various others. Fleisher’s performances are “marked by his nuanced yet spectacular technique, the clarity of his interpretations, his restrained, tasteful pedaling, and an astounding balance between the thumb and fingers of his left hand.”

In 1968, Fleisher began what has become a significant conducting career. He became the co-director of the Theatre Chamber Players of Kennedy Center as well as the conductor of the Annapolis, Maryland Symphony Orchestra. He served as associate conductor of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (1973–78) and as artistic director of Tanglewood Music Center (1985–97). With doctors finally able to correctly diagnose his conditions in the 1990s, Fleisher slowly regained control over his fingers. Tim Page wrote for the Washington Post in 1996, “I would rather listen to Fleisher, even in his current, delicate shape, than to most other pianists now before the public.”

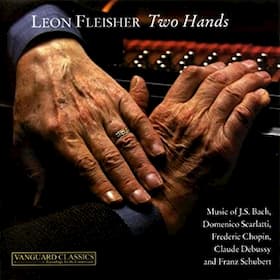

In 2004, Fleisher released an album simply titled, “Two Hands,” his first such album in 41 years. When he was awarded the Kennedy Center Honors in 2007, Fleisher wrote an open letter to The Washington Post, protesting the Bush White House policy regarding the Iraq War. Eventually, Fleisher did accept the award alongside actor-comedian-author Steve Martin, pop diva Diana Ross, filmmaker Martin Scorcese and songwriter Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. Speaking at the gala, Yo-Yo Ma recounted, “Fleisher’s interpretation of the Brahms’ 1st Piano Concerto is still seared into my brain.”

In 2004, Fleisher released an album simply titled, “Two Hands,” his first such album in 41 years. When he was awarded the Kennedy Center Honors in 2007, Fleisher wrote an open letter to The Washington Post, protesting the Bush White House policy regarding the Iraq War. Eventually, Fleisher did accept the award alongside actor-comedian-author Steve Martin, pop diva Diana Ross, filmmaker Martin Scorcese and songwriter Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. Speaking at the gala, Yo-Yo Ma recounted, “Fleisher’s interpretation of the Brahms’ 1st Piano Concerto is still seared into my brain.”

Throughout his phenomenal and inspirational career Fleisher strongly believed that “the purpose of music is to communicate from the heart to the heart,” and he famously quipped to a student, “Practice less, think more.”

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 21, D. 960 (Leon Fleisher, piano)