Gregory Kunde shines in Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello at the Royal Opera House, a revival of the 2017 production (originally reviewed for Interlude). From the victorious opening exclamation “Esulatate!” (Rejoice!) that rings all the way up to the rafters, to the fourth act “Niun mi tema” (Let no one fear me) when the deceived warrior kills his innocent wife in a fit of jealousy, Kunde delivers a thrilling Otello.

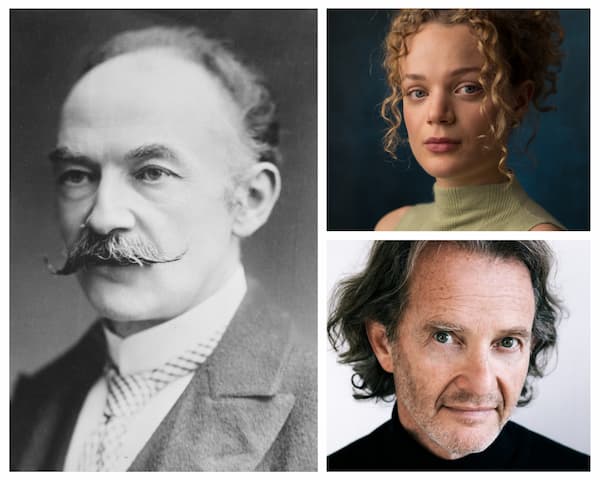

Gregory Kunde

He effortlessly arcs from the clarion strength of a tenore di forza, to the delicate phrasing of a lyrical belcantista. The short line “Oh! Gloria! Otello fu” (Oh glory, Otello’s day is done), so often just belted out without thought, is delivered by Kunde with a lush combination of shimmering beauty and heart-rending sensitivity. He magically conjures the power to seize the audience with a slow movement, a whisper, a soft whimper. At the very latest at this point we realise that we are being treated to a tenor who is not just good, but truly great.

A day after the performance, Interlude sat down with the relaxed and approachable singer in his dressing room to find out what makes such an artist.

Kunde’s rise to fame was a slow one, and it is hard to believe that the singer, who only attained global prominence beyond opera specialists in the last ten years, is on the verge of turning 66 years old. He doesn’t look, sound or act it. He has a youthful enthusiasm for his art, yet when he tells the story of his life, the roots of his artistic excellence become obvious: time, patience and professionalism.

Born in the small and decidedly unoperatic town of Kankakee, Illinois, Kunde studied and then spent seven years as a comprimario at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, sometimes singing just a line or two. He rates this a “hugely valuable and underrated experience,” taking the time to train, mature and cover. It gave him the opportunity to develop his voice and technique and watch and learn from the best: Alfredo Kraus, Jon Vickers, Luciano Pavarotti.

Gregory Kunde as Otello, Royal Opera House 2019

© Catherine Ashmore

He gave his full professional debut as Cassio in Verdi’s Otello in 1978. He did the rounds of US opera houses until his European debut in the Pearl Fishers at the Opera of Nice in 1986 and his Met debut in Massenet’s Manon in 1987.

Kunde gradually expanded his repertory until 1992: “that’s when I found Rossini; that changed my career.” He discovered the opere serie of Gioachino Rossini as well as the challenging tenor roles of the better-known Donizetti and Bellini operas. Kunde was called to Pesaro, the holy grail for Rossini lovers, to perform the rarely staged Ricciardo e Zoraide (under Alberto Zedda).

These were golden years for American belcanto tenors. Kunde was in good company with Chris Merritt, Bruce Ford, Blake Rockwell, all admired for their vocal agility, effortless coloraturas and catapulted top notes. Kunde’s warm and Italianate voice, thrilling top register (with an astounding high F) and strong stage presence made him a leading belcanto tenor of the 90s, bringing him to all of Europe’s great stages.

In 1994 Kunde was diagnosed and treated for testicular cancer. “There were no studies on how chemotherapy can affect the voice, so I just took the advice to not sing at all, barely even speaking for half a year.” His vocal cords emerged unscathed, and with a renewed vigour and appreciation for life he slowly worked his way back to the stage, little by little, vocalise by vocalise.

His voice retained the flexibility to sing the highly florid belcanto roles, but he also gradually moved towards baritenore roles, using a “more central voice.” He references the legendary Italian tenor Andrea Nozzari, for whose dark timbre Rossini specifically wrote the title role in Otello, a part with which Kunde’s career would become inextricably linked.

The famed Spanish tenor Alfredo Kraus, who was a valued teacher of Kunde, reportedly once said that until the age of 50 one doesn’t really know what a voice is capable of. But Kunde was 58 when he gave his first performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, widely considered the ultimate test for dramatic Italian tenors. But more remarkable than his success at this 2012 debut at La Fenice in Venice was the fact that Kunde had sung Rossini’s Otello, with its totally different vocal demands, only a few weeks earlier in the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. He repeated that feat in 2015, singing Rossini’s version at La Scala in July, followed by Verdi’s masterpiece at the Peralada Festival in August. “Yes, a real challenge,” he admits nearly laughing it off. “But it was ok, I couldn’t have done it in reverse order.”

Kunde’s modesty about this perhaps historically unique operatic feat illustrates the professionalism and deep humility of a consummate musician. It was likely also this comportment that prompted the Metropolitan Opera’s General Manager to call Kunde with twenty-four hours’ notice to stand by for a replacement of Aleksandr Antonenko in Samson and Delilah in March 2019, a role Kunde hadn’t sung in two years. Having only flown in at noon of the performance day, Kunde with no fuss sat around in the green room, until he was called to replace the ailing Antonenko in the second act. Kunde garnered rapturous applause. “I hadn’t sung at the Met for 12 years,” Kunde says nonchalantly, as if there were nothing more than simple professionalism that would cause a mid-sixty-year-old father of one to replace a much younger colleague at short notice in a notoriously difficult role.

So what makes Kunde’s Otello (Verdi) so arrestingly convincing? “It’s not about vocal power. You need to be vocally in good shape, yes, but you need to be dramatically experienced.” He hesitates for a moment. “It’s actually not about the singing. It’s about the listening; you need to hear everything that is going on around you.”

We interrupt the interview as the second cast Otello drops by to remind him of their lunch date. They and their Cassio are going to lunch. “We’re all friends. Diva-like behaviour and volatile moodiness was never my thing and is no longer acceptable in opera. Times have changed.”

I wouldn’t quite agree with that last statement, but Kunde is certainly a shining example of the down-to-earth and supportive professionalism that any colleague would cherish. And he beautifully embodies patience, a virtue nearly lost in today’s live-fast-die-young and hyper-competitive opera world. Gregory Kunde is living proof that they still make great tenors like they used to. And who would have guessed they made them in Illinois?

Performance attended: 19 December, 2019