Musical Offering, BWV 1079

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra

Ton Koopman

Frederick The Great

Frederick the Great of Prussia, affectionately known as “Der Alte Fritz” (Old Fritz) is generally known as a brilliant military campaigner who established the reputation of Prussian military might. In addition, he was praised for embracing the principles of the Enlightenment, which allowed for freedom of speech and the press, and the right to hold private property. The German Romantic writer Jean Paul — actually born Johann Paul Friedrich Richter — compared Frederick the Great to the nativity paintings by Antonio da Correggio, “with light radiating from the Holy Infant upon those standing around.” The principles of the Enlightenment also fostered the sciences, education and the Arts. Frederick modernized the Prussian civil service and school system, regularly corresponded with Voltaire who also visited Old Fritz in Potsdam, and composed 121 flute sonatas, 4 flute concertos and even a symphony! Yet not everybody was impressed by Frederick the Great, with Werner Hegemann classifying him “as one of the most obnoxious figures in the history of the world.” What made Old Fritz obnoxious, above all, were certain mannerisms associated with his “unnatural” sexual tendencies. During his teenage years, he was forced to watch the public execution of his lover Hans von Katte, and he clearly was not going to marry a woman. As a result he became increasingly lonely, isolated, and some voices say, increasingly astringent. While we cannot hope to untangle the baffling and inaccessible personality of “Old Fritz,” we can get an idea of what J.S. Bach thought of him, of course, all encoded in music.

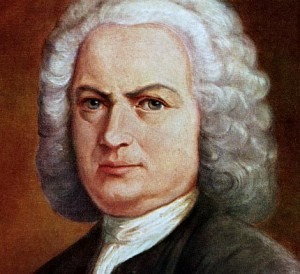

Bach

In 1738, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach — fifth son of Johann Sebastian Bach and Maria Barbara Bach — was appointed as harpsichordist and court composer at Frederick’s summer palace Sanscouci in Potsdam. Over the years, Frederick had amassed a rather substantial collection of instruments, and Carl Philipp was eager for dad to have a look. For one reason or another, the Old Bach, pleading ill health always declined. However, in 1747, Frederick procured several experimental fortepianos developed by Gottfried Silbermann, the eminent instrument maker of his day. And so it came to pass that the Old Bach met the Old Fritz on 7 May 1747. For this special occasion, Frederick canceled his evening concert and invited Bach to try out his new fortepianos. At some point during the evening, Frederick presented Bach with a long and complex musical theme, full of chromatic scales and awkward leaps, and asked him to improvise a three-voice fugue. Frederick, as is well known, completely scorned the old-fashioned polyphony and favored the simple, entertaining and balanced melodies of the gallant musical style, which was all the rage at the courts throughout Europe. Throughout his reign, Old Fritz made it a habit to humiliate his guests, and apparently had the same plans for the Old Bach. Yet Johann Sebastian did not flinch, and expertly improvised on the theme with three obbligato parts. Old Fritz was much impressed and later recalled that Old Bach’s visit was “one of the most unforgettable and richest experiences of his life.” However, on that memorable evening, Old Fritz was not yet finished and he challenged the Old Bach to improvise a six-voice fugue on the theme. By this time, Bach was probably cognizant of the King’s intentions and replied that he would need to work this out in a score and send it later. And so it came to pass that two months later, Bach published a set of compositions on this “Royal Theme”, which has become known as The Musical Offering. It included two “Ricercars” — two fugues in antiquarian notation for three and six voices, respectively — and a “Triosonata.” However, Bach’s impressions of the Old Fritz emerge most forcefully in 10 riddle canons, in which the performer has to musically decipher the entrance of successive voices via cryptic symbols, or in this case, through Latin inscriptions. The number 10 and the choice of Latin as the language are highly significant. Ten, of course, is the number of commandments, and in translated usage the word “canon” actually means law! And Latin was the language of the church and of science, whereas Frederick’s court only spoke fashionable French. One canon for two voices is inscribed “Notulis crescentibus crescat Fortuna Regis” (may the fortunes of the King increase like the length of the notes), and has to be solved by increasing the relative length of the notes. Of course, this becomes completely nonsensical after a while as the augmented voice will reach such extended duration that performers will have no choice but to stop. The “Canon per tonos” (endlessly rising canon) is inscribed “Ascendenteque Modulatione ascendat Gloria Regis” (as the modulation rises, so may the King’s glory). It juxtaposes the King’s theme against a two-voice canon at the fifth. Because of the modulation, the canon finished one tone higher than it started, and because it lacks a final cadence, it goes on forever. In a musical sense, the King’s glory is simply going nowhere. James Gaines has suggested that Bach also included chorale motifs and church music — which Frederick hated with a vengeance — to steer Old Fritz towards a path of spiritual redemption. It all seems to suggest that the Old Bach — a devout Lutheran, dedicated family man and father of 20 children — did not seem to have a particularly high opinion of Old Fritz — the secular, fashionable and homosexual Great of Prussia. Old Bach got royally paid for his composition and dedication but there is no evidence to suggest that Old Fritz — having clearly understood the message Old Bach was sending him — ever tried to decipher the riddle canons.

So interesting as I’ve just watched the play The Score starring Brian Cox. Wish I’d read this first!