Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2”

American artist Robert Motherwell (1915–1991) grew up on the Pacific Coast, spending his time between California and Washington state. At Stanford University, where he received a BA in philosophy, he discovered modernism, and this became a life-long passion. He went on to start a philosophy Ph.D. at Harvard before moving to New York and attending Columbia University. His interest shifted from philosophy to art, and he spent time with a group of French Surrealists (Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and André Masson) who were in exile in the US.

Robert Motherwell

His background in philosophy made him examine the American art scene, and he declared that ‘everybody who liked modern art was copying it. Gorky was copying Picasso. Pollock was copying Picasso. De Kooning was copying Picasso’. This led him to lay the foundations for Abstract Expressionism. It wasn’t surrealism but was a new American movement. With the support of patron Peggy Guggenheim, he had his first one-man show at her Art of this Century gallery in 1944. By the mid-1940s, he had become the spokesman for avant-garde art in America.

Throughout the 1950s, Motherwell taught painting in New York at Hunter College and in North Carolina at Black Mountain College. Among his students were Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Kenneth Noland. Black Mountain College, founded in 1933, was an important arts centre and ‘incubator for the American avant-garde’, with its faculty and students including some of the leading artists and experimental musicians of the mid-century, such as Josef and Anni Albers (from the Bauhaus), Ruth Asawa, John Cage, Robert Creeley, Merce Cunningham, Max Dehn, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, Walter Gropius, Ray Johnson, Franz Kline, Charles Olson, M. C. Richards, Dorothea Rockburne, Michael Rumaker, and Aaron Siskind. The college closed in 1957 because of financial problems.

Motherwell’s art is bold in its use of colours and brushwork. The formats are large-scale. Unlike other Abstract Expressionists, Motherwell tied his art to real-world references, his long-standing series Elegies to the Spanish Republic being his most significant in that regard. The series was made up of over 100 paintings created over a 20-year period.

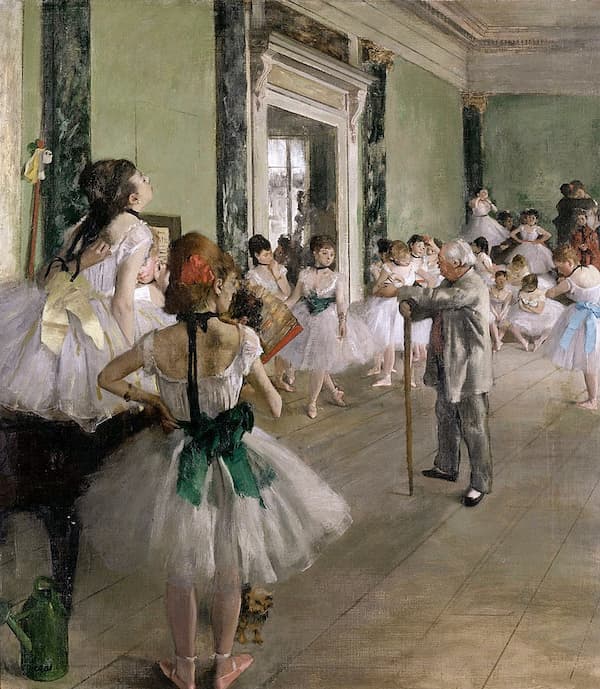

Motherwell: Elegy to the Spanish Republic, 108, 1965-67 (New York Music of Modern Art)

He used simple forms and large, flat planes of colour to gain an emotional response from his viewers, always maintaining that ‘art is an expression of the inner self’.

American composer Kenneth Fuchs (b. 1956) took five paintings by Motherwell as the basis for his second string quartet, Where Have You Been?. It was commissioned by the Trustees of Manhattan School of Music in honour of Gordon K. Greenfield on the occasion of his retirement as Chairman of the Board, 1981-1994, and to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the School and the 20th anniversary of the American String Quartet, quartet-in-residence at Manhattan School of Music.

Kenneth Fuchs (photo by Dario Acosta)

The collages Fuchs used were exhibited at the Knoedler Gallery in New York. For Motherwell, the collages were ‘a kind of diary—a privately coded diary, not made with an autobiographical intention, but one that functions in an associative way for me’ and in them Fuchs saw a key to a current problem he was having in his music. He wanted to use the idea of a musical collage to juxtapose and reorganize ‘a few disparate musical ideas’. His work makes a parallel in sound with what he experienced in viewing the Motherwell works. These Motherwell collages include music paper and music symbols, and Fuchs responded to that parallel to his writing.

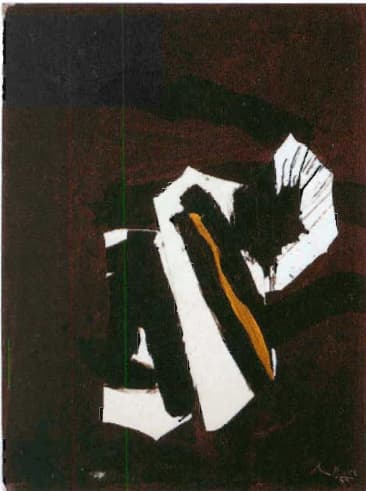

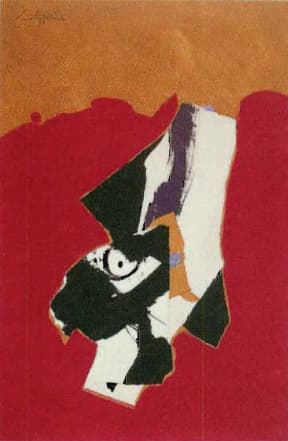

The first movement is, by his description ‘dark, turbulent, and dissonant, with jagged and angular lines’.

Motherwell: Heart of Darkness

Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2” – I. Heart of Darkness (The American String Quartet)

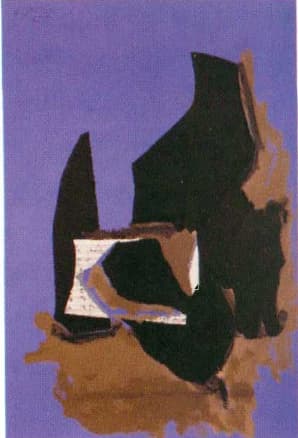

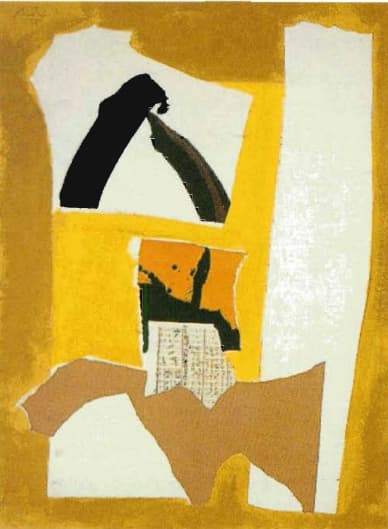

As a contrast, and in keeping with the title, it’s followed by a movement that is ‘extremely lyrical and diatonic, with delicate minimalist gestures’.

Motherwell: The Other Side

Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2” – II. The Other Side (The American String Quartet)

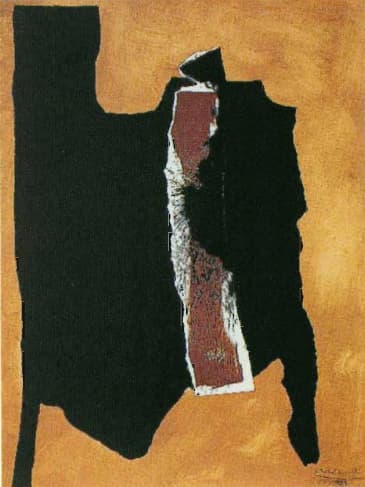

The third movement tries to melt the ideas of the first two movements and their two different pitch classes (E-flat, F-sharp, G, A, B-flat, C-sharp, D for the first movement; C, D, E, F-sharp, G, A, and B for the second movement), to create ‘kind of forced marriage that ends badly’.

Motherwell: The Marriage

Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2” – III. The Marriage (The American String Quartet)

The longest movement, the fourth, functions as the development section of the work as a whole, exploring the musical ideas presented in the first three movements, both alone and in relation to each other.

Motherwell: They Are Not Heard at All

Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2” – IV. They Are Not Heard at All (The American String Quartet)

The final movement looks back on the earlier movement and ‘affirms the power of 1 experience, observation, and meditation’.

Motherwell: Where Have You Been?

Kenneth Fuchs: Where Have You Been, “String Quartet No. 2” – V. Where Have You Been? (The American String Quartet)

Fuchs said about his work that he used his ‘responses to the collages as emotional guideposts to explore my current musical concerns: use of pitch classes, minimalism, diatonicism, and serialised musical elements’. The use of the string quartet gave Fuchs an ensemble that was both pure in sound and small in scale to allow him the greatest freedom in his explorations. He compared himself with an Abstract Expressionist painter: ‘poised, with as much knowledge, craft, and discipline as possible at the ready, I let myself be guided by my own sensibility and sense of discretion, allowing musical materials to flow with as much psychic autonomy as possible’.

The premiere of the piece was given at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, New York, on 9 May 1994. In the music, Fuch’s lyrical gift comes to the fore, as does his command of rhythm and voice. He finds the drama in the collages and in the third movement, which clearly depicts the bad end to The Marriage. For Motherwell, tapping into the unconscious was an important part of abstract expressionism – painters should be able to exploit the idea of automatism, where the ‘artist suppresses conscious control over the making process, allowing the unconscious mind to have great sway’. In the same way, Fuchs sought ‘to create a mood, a state of feeling. through a series of musical gestures’.

It’s hard to think of abstract expressionism in music, but Fuchs has succeeded not in illustrating the works but in telling us how he perceived them.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter