Johannes Brahms had trouble with women. He objectified most of them, thought of them as either Madonnas or whores, and heartily agreed with prevailing social attitudes that they should concentrate on Kinder, Küche, Kirche (Children, Kitchen, Church), to quote a phrase that was common during his lifetime.

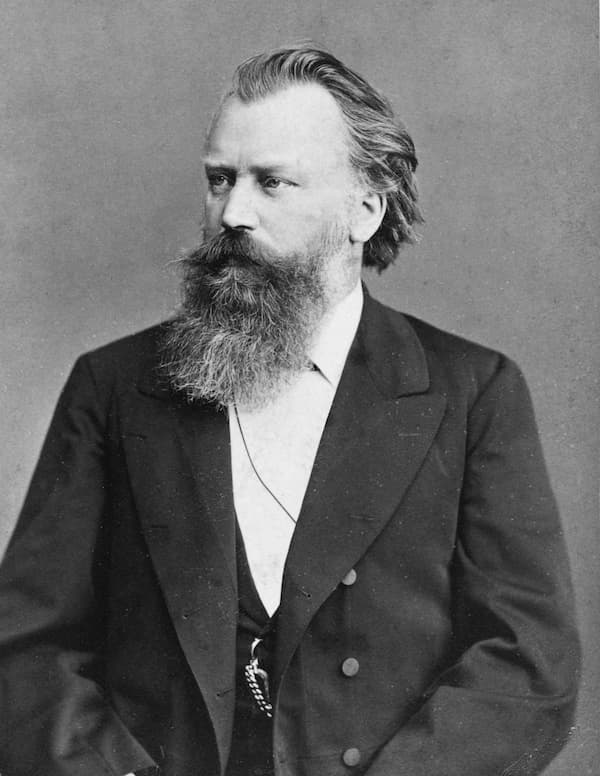

Johannes Brahms, c. 1885

And yet, despite his best efforts to stay free from emotional attachments to women, over the course of his life, he had deeply meaningful relationships with several of them.

Today, we’re looking at six of the women he was closest to and how they impacted his life, work, and music.

Christiane Nissen Brahms (1789-1865)

Christiane Nissen Brahms

Christiane Nissen was born to a tailor in Hamburg, Germany, in 1789.

She began working as a seamstress when she was just thirteen. During her twenties, she worked as a servant before returning to seamstress. Eventually, she moved in with her sister and brother-in-law and helped to run their shop, where they sold sewing notions.

To make some extra money, the family took in a lodger. He was a musician by the name of Johann Jakob Brahms. Eight days into his stay, he proposed to Christiane.

The proposal was surprising, to say the least. He was 24, she was 41. But she accepted, and they were married soon afterward, on 9 June 1830. They would have three children together: Elise, Johannes, and Fritz.

Brahms biographer Jan Swafford describes Christiane as “small, sickly, gimpy from a short leg, plain of face though she had enchanting blue eyes.” But she was a talented cook and housekeeper, and Johannes loved her deeply.

Unfortunately, her marriage deteriorated by the 1860s; the age difference and other issues caught up with the couple, and they separated. She died in 1865 after having a stroke.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896)

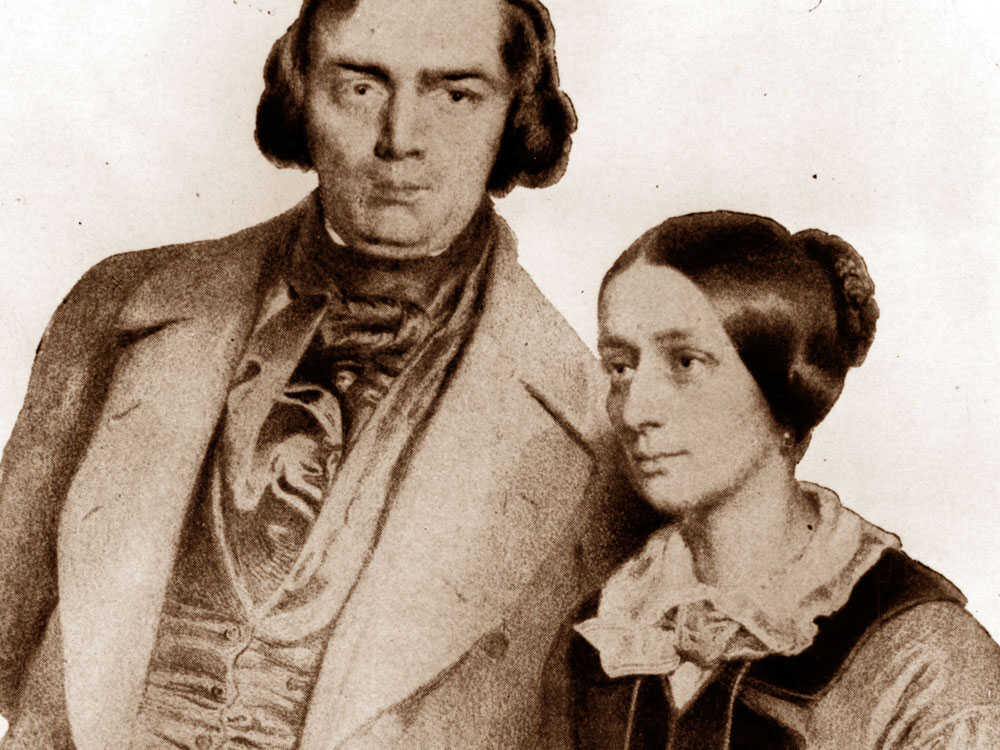

Robert and Clara Schumann

Clara Wieck Schumann was born to Friedrich Wieck, a piano teacher and music store owner, and his wife, singer Mariane.

Wieck was determined to make his daughter into a prodigy pianist as a kind of walking advertisement for his methods. He got very lucky: Clara became one of the most celebrated piano prodigies of her era.

As a teenager, she fell in love with one of her father’s students, Robert Schumann. Despite her father’s protestations, she married him in 1840.

On 1 October 1853, Clara and Robert met a 20-year-old Johannes Brahms, who nervously visited their home to network. The Schumanns were immediately taken by the music of this young genius from Hamburg. They invited Brahms to stay for a few weeks.

Robert Schumann believed him to be the future of music, and he wrote an article saying as much that was distributed in a magazine called the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

Brahms was starstruck by Robert’s faith in him…and, awkwardly, found himself falling in love with Clara.

Unfortunately, Robert Schumann’s mental health, never good, deteriorated drastically over the next few months. He attempted suicide in February 1854 and agreed to be admitted into an asylum. He would never return home.

After Robert’s departure, Brahms stayed to comfort Clara – who was pregnant at the time – and help with the children. Robert died in the summer of 1856.

We don’t know exactly what conversations Brahms had with Clara during this time. We do know that the idea of being in a marriage where his wife would out-earn him was unappealing, and Clara didn’t want any more children. Ultimately, they decided not to marry.

However, they stayed close friends for the rest of their lives, and neither of them married anyone else.

Learn more about the relationship between Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Elise Brahms Grund (1831-1892)

Elise was the eldest child of Johann Jakob and Christiane Brahms, born in February 1831, eight months after her parents’ wedding.

She suffered from headaches and was often bedridden with chronic pain. Because of her health issues, combined with the sexist mores of the time, she wasn’t able to get a good education. Christiane’s purportedly affectionate nickname for her was “the fat dumb peasant.” Her little brother Johannes, however, loved her.

In the 1860s, her parents split, although they never formally divorced. Elise’s mother was her ally in the household. The rift in the household deepened after Johann Jakob refused to pay for their expenses.

Unfortunately for Elise, her mother died suddenly of a stroke in 1865. Her father remarried. The situation left her vulnerable, and she ended up renting a room from friends, being subsidised by Johannes.

In 1871, when she was forty, she married a widowed watchmaker named Christian Grund, who was twenty years her senior. Johannes urged her not to, believing she was too naive and inexperienced to be a successful wife and mother. He even offered to pay for her room and board at a convent. (Clara Schumann, on the other hand, perhaps remembering how her father had once disapproved of her marriage to Robert, urged Johannes to support his sister.)

Happily, Johannes’s doubts were misplaced, and the marriage was happy. The two even had a child together, but unfortunately, the baby died a few days after it was born.

Her husband died in 1888 and she died in 1892. The letters Johannes had written to her were all returned to him after her death. Interestingly, although Brahms burned most other correspondences, he couldn’t bring himself to burn Elise’s.

Learn more about Brahms and his relationships with his family.

Agathe von Siebold Schütte (1835-1909)

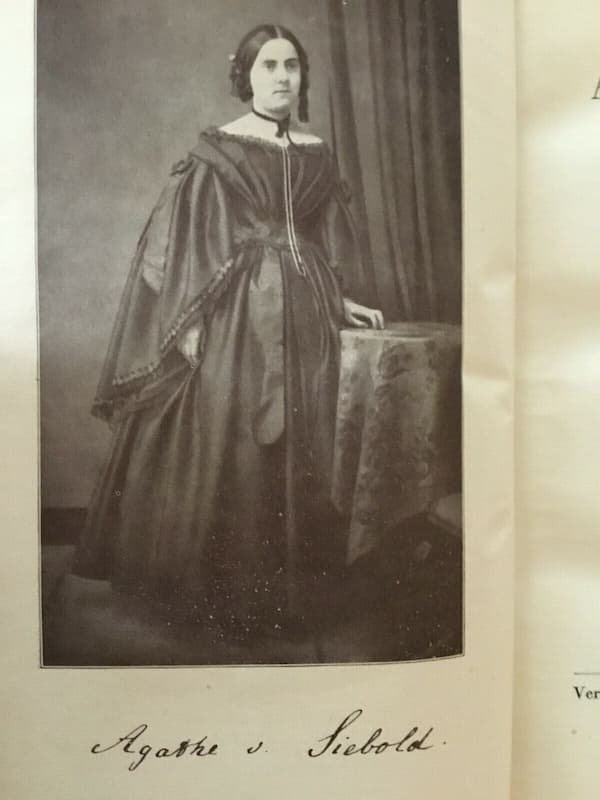

Agathe von Siebold Schütte

In July 1858, two years after the death of Robert Schumann, Brahms went to the town of Göttingen to visit friends and conduct the local women’s chorus. Clara Schumann, her composer brother, and five of her children also came with her.

During the trip, he befriended one of the sopranos in the chorus, a young woman named Agathe von Siebold. She had lovely dark hair, an attractive figure, and a playful sense of humour. She was also an amateur composer.

Their friend group stayed out late into the summer evenings, laughing and playing games, and Brahms and Agathe soon started flirting. However, he gave away to her that he still had Clara on a pedestal, telling Agathe at one point that he had to also walk with Clara occasionally so she wouldn’t get jealous.

He was right: Clara was so upset when she caught Brahms and Agathe embracing that she abruptly cut the vacation short.

After New Year’s, her family politely encouraged Brahms to propose, so that there would be no risk to their daughter’s reputation. He obliged, but they didn’t set a date for the wedding.

Unfortunately, simultaneously, Brahms experienced the relative failure of his first piano concerto. He claimed he could never face a wife after enduring any similar professional failures.

He wrote Agathe a rather appalling letter with the lines, “I love you! I must see you again! But I must not wear fetters!” Agathe interpreted this as shorthand for “Be my mistress, but not my wife.” She replied by sending her engagement ring back to him. The marriage was off.

She never forgot the relationship. In fact, later in life, she wrote a novel inspired by it. As for his part, Brahms included a theme made out of the letters of Agathe’s name in several musical works, including his second string sextet.

Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 In G Major Op. 36

Julie Schumann (1845-1872)

Julie Schumann

Julie Schumann was Robert and Clara Schumann’s third child. She had been seven years old when her father left home for the asylum and Johannes Brahms moved in to help her mother.

Unfortunately, Julie’s health was poor. She traveled to stay with family friends in more southern climates, hoping to grow stronger.

During one of those trips, she met an Italian count, who fell in love with her. In 1869, she married him.

Johannes Brahms served as witness. Little did Julie know that doing so was torture. He’d fallen in love with her, but, given the complicated dynamics at play, he hadn’t verbalised his love fast enough – and now she was lost to him forever.

Johannes Brahms: Alto Rhapsody

He had confusing romantic feelings for Julie that he never really verbalised, instead choosing to write them into his Alto Rhapsody.

He wrote to his publisher, “Here I’ve written a bridal song for the Schumann countess – but I wrote it with anger, with wrath! What do you expect!”

Clara Schumann had feared that childbearing would weaken Julie, and tragically, her fears were well-founded. She had two children, her health weakened, and she died of tuberculosis in Paris in 1872 when pregnant with her third.

Learn more about what happened to the Schumann children.

Elisabeth von Stockhausen Herzogenberg (1847-1892)

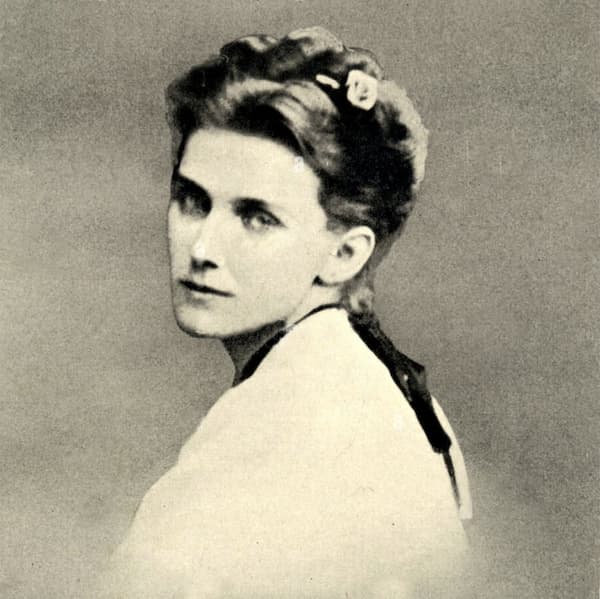

Elisabeth and Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Elisabeth von Stockhausen was born in 1847. She was a musical child from a musical family (her father had studied piano with Chopin), and in the winter of 1863-64, she began taking piano lessons from Johannes Brahms. He found her very attractive and was so unnerved by her that he passed her to a colleague to teach.

Elisabeth met Heinrich von Herzogenberg in 1865, and they married the following year. After she was married, Brahms grew less afraid of her and felt freer to befriend her and her husband properly.

The couple moved to Graz before settling in Leipzig in 1872 and then Berlin in 1885. Heinrich taught music; Elisabeth maintained a cheerful household and charming correspondence; and both played piano and composed. Here are some of her pieces:

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: 8 Clavierstücke

To their devastation, they were unable to have children, so their musical friends became their family. Brahms became an especially treasured friend.

He was deeply impressed by Elisabeth’s musical opinion and began sending her work to get her feedback. “You should know and believe that you are among the few persons whom one holds so dear that one cannot tell them so,” he wrote to her.

The couple’s health was not great, and in 1891, they went to the Italian town of Sanremo, where Elisabeth died in 1892 when she was just forty-four years old.

Brahms wrote to her grief-stricken husband: “It is vain to attempt any expression of the feelings that absorb me so completely. You know how unutterably I myself suffer from the loss of your beloved wife and can gauge accordingly my emotions in thinking of you, who were associated with her by the closest possible human ties.”

He dedicated his Rhapsodies, op. 79 to her.

Brahms: Rhapsodie No.1, Op.79

Read more about Brahms and Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter