In 1895, Edvard Grieg came across the book Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid) by Arne Gaborg. He immediately was fire and flame writing to his friend Julius Röntgen, “In the last few days I have been occupied with a very peculiar poem: it is a recently published book in “Landsmål” by Arne Garborg, Haugtussa. It is quite a brilliant book, where the music is really already composed. One just needs to write it down.”

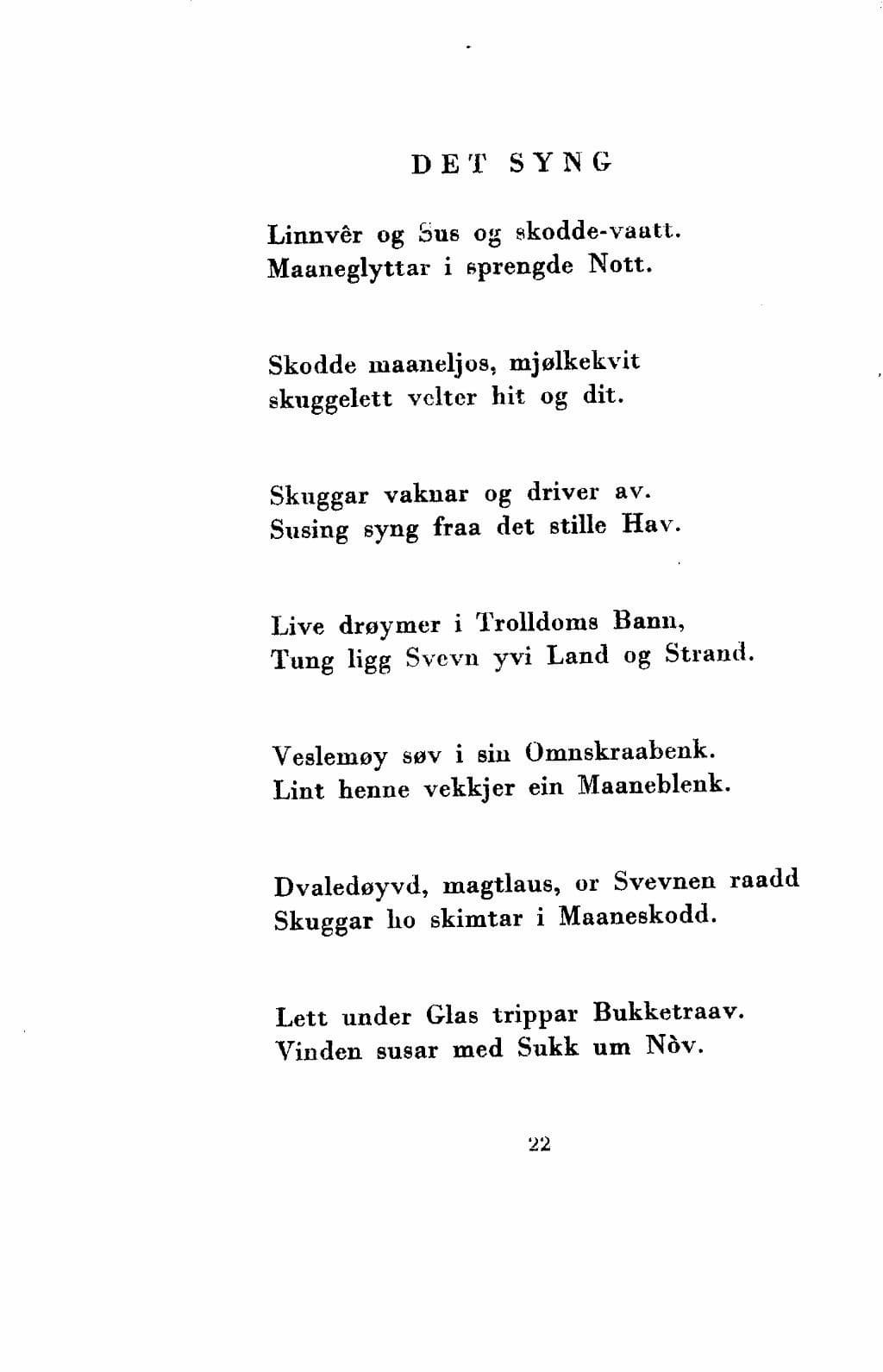

Arne Garborg: Haugtussa

The “Landsmål” language was a construct by a Norwegian linguist who drew together a variety of Norwegian peasant dialects in the context of Norway’s struggles for independence and the creation of a national identity. “This language differs from the more common “Bokmål Norwegian,” which was derived from the Danish, through the inclusion of a specifically Norwegian vocabulary and a multitude of grammatical forms.”

In the event, Grieg immediately began to work on a song cycle and set roughly 20 of the 71 verses to music. After this initial burst of activity, Grieg took a rather lengthy pause, informing Röntgen that “for the time being, Haugtussa still sleeps.” It took Grieg another two years before it reached its final form of eight songs. It certainly was worth the wait as Grieg considered his settings as “the finest songs I have ever written.”

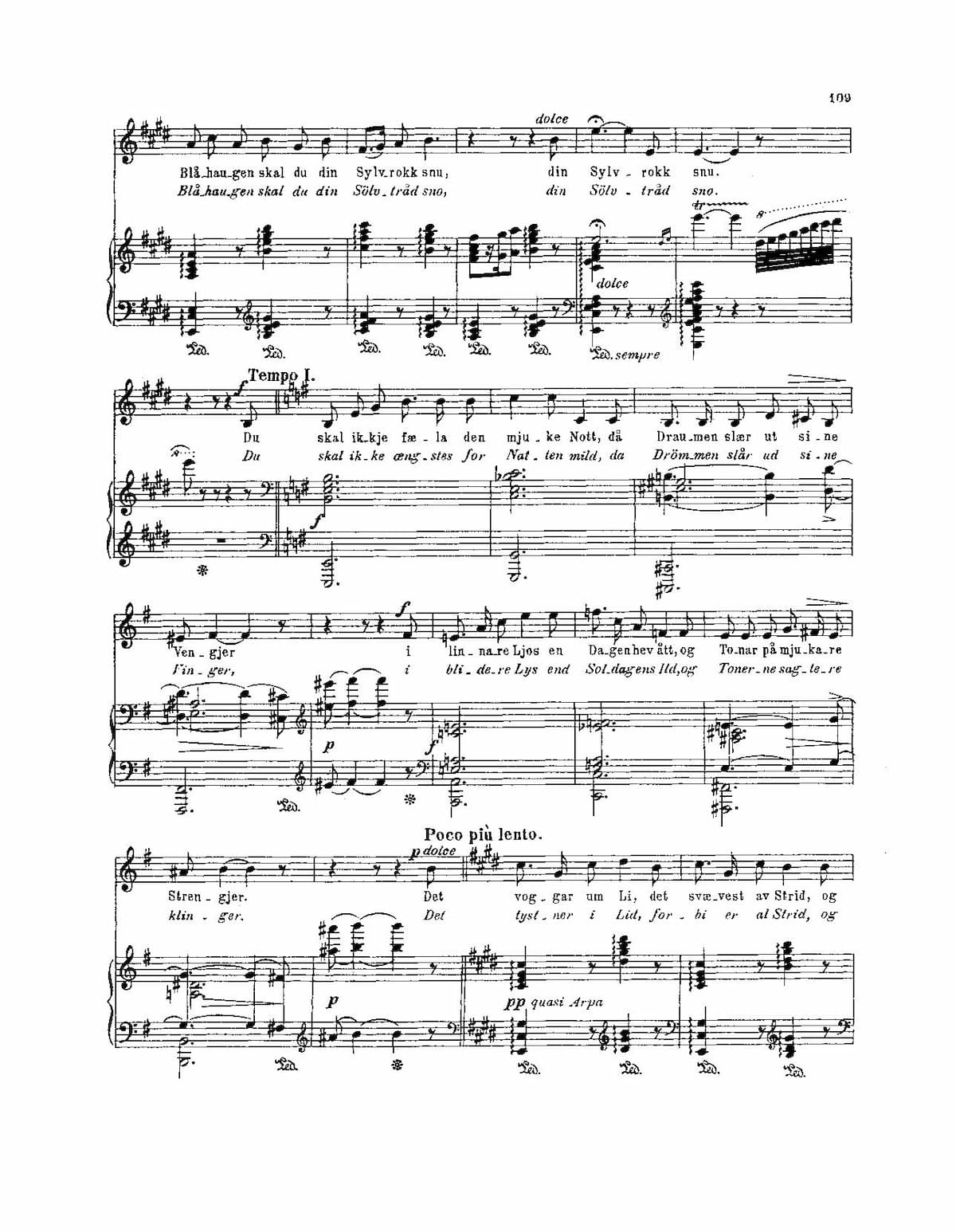

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “The Enticement” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Just knowing the dream, just knowing the song,

The tune will hold fast in your mem’ry;

Seductively beckoning all the day long,

Its sounds echo deep in each reverie.

Bewitch’d by your spell,

With me you must dwell;

Your spinning-wheel tread in the misty Blue-Fell!

You never shall fear the soft gentle night,

When dreams soar aloft on stretch’d wings

In transport beyond day’s aura so bright,

Midst sounds borne on sighing, hush’d strings.

The slopes yield to sleep,

Peace reigns on each steep,

As day’s strife gives way to contentment so deep.

You never shall fear the chance wildness of love,

Forgetful and false in its wooing;

It conquers with fire or tames meek as a dove;

The bear’s fierce anger subduing.

Bewitched by your spell,

With me you shall dwell;

Your spinning-wheel tread in the misty Blue-Fell!

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

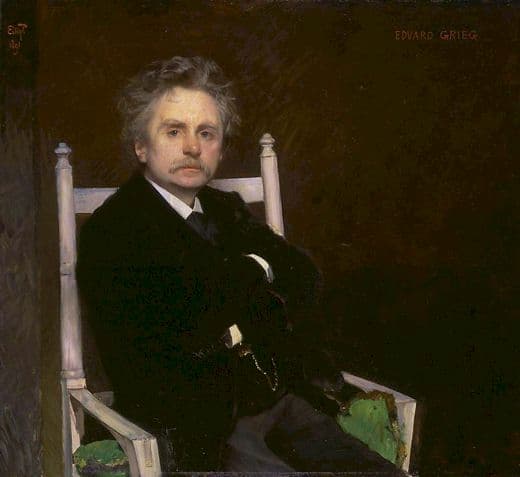

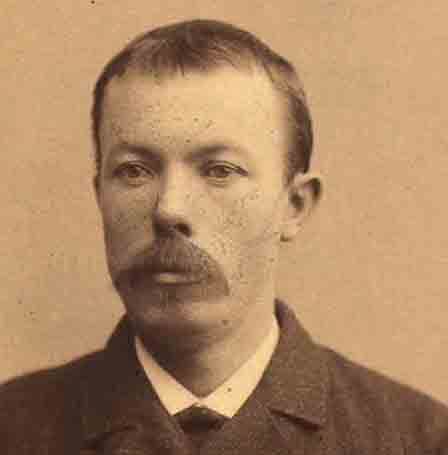

Edvard Grieg, 1891

Grieg described the poem as “a masterwork, full of originality, simplicity and depth, with an indescribable richness of colour.” It tells the story of Veslemøy, a young herding girl with clairvoyant powers, and her experience with love and rejection. Wanting to escape the real world, Veslemøy seeks to connect with nature and the underworld.

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “Young Maiden” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

She is lovely, so lissom, so lithe,

Her dark features finely drawn,

With deep-set, silvery grey eyes,

Her manner impassive and calm.

There hovers an air round her head

Of a dreamlike fragility;

Each gesture, each word that is said,

She imbues with tranquillity.

Neath her brow, low and strikingly fair,

Bright eyes shine though as through a veil,

As if gazing afar through that stare

To regions beyond this pale.

But, her breathing, so halting reveals

The slight tremor around her mouth,

Yet her fears and the frailness she feels

Are concealed by her glow,

Her youth, by her glow, her youth.

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Setting only a small part of Haugtussa, Grieg still manages to portray the poem in its entirety “within the bounds of his dramaturgical concept.” The eight songs are arranged in symmetrical pairs, forming a carefully constructed dramatic arch. The fourth and fifth songs provide the climax, each surrounded by pastoral and melancholic setting, and “opening and closing with a pair of lyrical and mystical songs.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “Blueberry Slope” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Ah! Look, how this field’s abloom!

Let’s stop to rest here, my Bossie!

We may help ourselves I presume;

Just eat, so your coat grows glossy!

Such berries! I’ve ne’er seen the like!

The slope their blue-hue they lend.

I’ve hunger too, from our hike;

We’ll stay and feast ’til day’s end!

But, what if the bear should come?

There need must be room here for two.

With him here, my voice would fall dumb;

that scamper’s provok’d with a “boo”.

I might say: “Please help yourself!

My goodness, now don’t be shy!

It’s you first, (I’ll wait myself)

You own what’s under the sky”.

But were it the sly, red fox,

He’d soon taste the sting of my hand-staff,

I’d chase him to give him sharp knocks,

Were he kin to the Pope, this riffraff!

This loathsome, sneaky red lout!

He steals both our sheep and lambs.

His elegant looks, there’s no doubt,

Mask his cruel treachery and shams.

But, were it the wolf, we dread,

As false as our bailiff, the mean brute,

A birch-club I’d strike at his head

And pray that I’d break his unclean snoot.

The ewes and their new-borns succumb;

Poor mothers lost much of her flock.

I swear! If he only should come,

My blows the wretch would bemock.

But, were it that splendid boy,

the one from yon brushwood clearing,

Once more a big smack I’d deploy,

But this time, one quite endearing!

What thoughts! My word, how absurd…

My fantasy always at fault!

I must go tend to my herd;

Dear Bossie’s dreaming of salt.

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

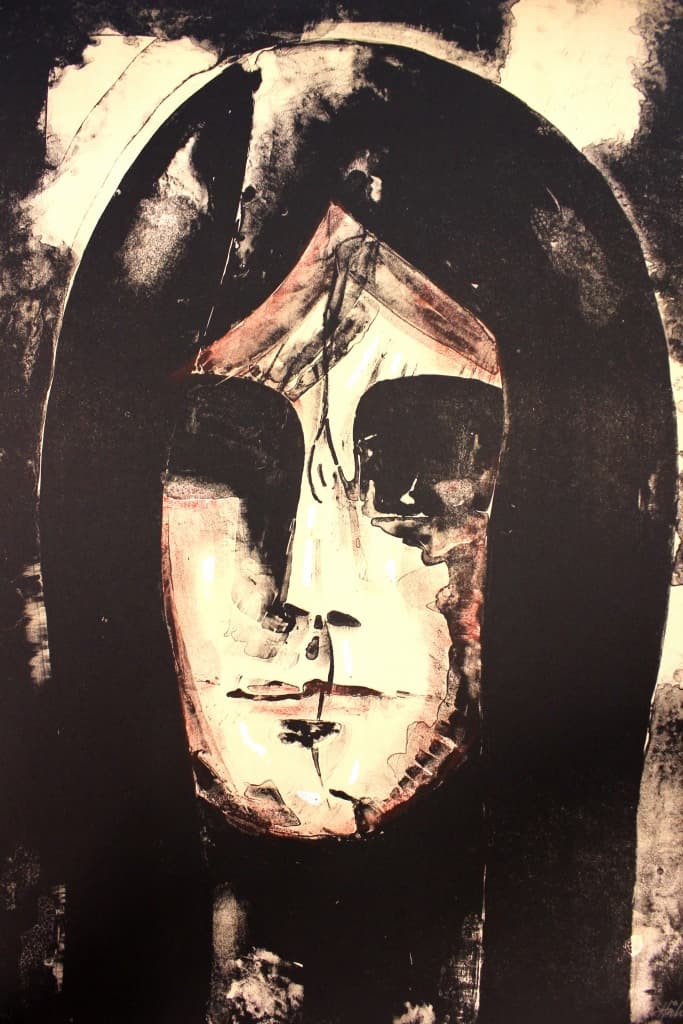

Arne Garborg

As Grieg once told his biographer Henry Finck in 1903, “For me, it is important when I compose songs, not first and foremost to make music, but above all to give expression to the poet’s innermost intentions. To let the poem reveal itself and to intensify it, that was my task. If this task is tackled, then the music is also successful. Not otherwise, no matter how celestially beautiful it may be.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “The Tryst” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

A Sunday morning, she waits upon the hill,

Each longing thought aglow with sweet emotion,

Each heartbeat filled with tender, new devotion;

Love’s dream awakens, tremulous and still.

A shimmering glow the hill, then, seems to cover;

She flushed with joy; he’s come, her handsome lover!

Though, now he’s there, she yearns to faint away,

But stops entranced and turns her eyes in greeting;

They both reach out, there warm hands firmly meeting,

And thus they stand, not knowing what to say.

These graceless words burst forth, yet him enthral:

“But, tell me, oh! When did you grow so tall?”

As daylight yields to evenings mild embrace,

Each slowly drawn towards the other’s presence,

Their arms entwine in silent acquiescence,

Their lips with trembling ardour meet; hearts enlace.

Cares slip away. Night shielding them from harm;

She sleeps content now, cradled in his arm!

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Edvard Grieg was enormously popular both inside and outside Norway, but his international fame is primarily based on a relatively small number of instrumental works. It always comes as a surprise that Grieg wrote approximately 60 choral works and more than 180 songs. As a scholar writes, “Grieg’s songs reveal his musical idiom more clearly, directly and eloquently than any other group of works.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “Love” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

That boy’s a rogue, yet my heart he’s captured,

A bird ensnared, I’m a bird enraptured;

That roguish boy goes his own proud way,

He knows this bird never from him will stray.

Oh, would you’d bind me with braid and twining,

With burning knots to allay my pining.

Oh, would you drew me so close, so tight,

My soul set free could take flight.

If I knew magic to conjure troll-spells,

I’d grow inside you, where your soul dwells,

I’d grow inside you, beneath your skin,

Be with you only, your heart within.

It’s I who carry you in my heart now,

You hold my mind in full power and part now;

The slightest impulse, each thought, the same,

They whisper solely your name.

As cloudless skies let the radiant sun through,

My only thought this: it shines upon you!

When dusk descends and day dims its light,

Will he be thinking of me tonight?

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67

The primary reason why songs play such an prominent role in Grieg’s musical output can easily be attributed to the influence of his wife Nina Hagerup, who served as the source of inspiration from the beginning of his career. In addition, the quality of Grieg’s songs are the “result of his deep knowledge and understanding of literature, as demonstrated by innumerable quotes and insightful commentary in his letters.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “Kidlings’ Dance” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

Oh hip, oh hop, turn and spin, old top, on this wonderful day;

Oh, nip and knock, as you stomp and sock,

In this spirited fray.

Oh, now here’s Run-in-the-Sun,

Oh, now here’s Fun-in-the-Sun,

Oh, now here’s Dance-in the-Lea,

And there’s Sir Prance-in-the-Lea,

A time to jolly, for carefree folly,

This bright, sunny day.

Oh, nudge his neck, take a plunge and peck,

Butt him off his toes;

Oh, crack the whip, as you trot and flip;

He’ll land on his nose.

Oh, now there’s Lick-in-the-Sun,

Oh, now there’s Kick-in-the-Sun,

Oh, now there’s Play-in-the-Lea,

And here’s Miss Bray-in-the-Lea;

Time now for silence; no more deny, thence,

This nook its repose!

So, ends the lull; hear that cracking skull,

Now take that, ha, ha, ha!

So, prod and push, smartly smack his puss,

Now get yours, baa baa baa!

Oh, now they roll in a ring,

Oh, now they sway and they swing,

Oh, now they perch: tippy-toe,

Oops, now they lurch domino;

Again, it’s oops, ah, and then it’s whoops, ah,

Then just: tra-la-la!

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Grieg was well aware that his songs would find little circulation outside Scandinavia. As he wrote, “even my best songs can never become popular. If the Nordic language were a cultural icon, then perhaps—just as we always sing the masters of the German Lied, even Schumann and Schubert, in the original, in spite of the many translations we have.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “Hurtful Day” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

She marked the days, the hours, each eve’, as well,

Till Sunday came; he promised and did tell her;

Should hailstones pour down over the slopes pell-mell;

Still, would they meet there in the goatherd’s shelter.

But, Sunday came and passed, all mist and rain;

In tears, behind a bush, she awaited him in vain.

Like to a bird with broken, bleeding wing,

Tears flow, like drops of blood to vent her sorrow,

She seeks her bed to ease the sickening sting;

Yet, tosses nightlong, sleepless till the morrow.

Hot tears again stream down, her cheeks to sear.

Now must she die; she’s lost her love so dear.

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Arne Garborg: Haugtussa

A lack of familiarity with the Norwegian language presented a hurdle for foreign audiences. Although Grieg songs were usually published in translation in order to increase the circulation and sales in foreign markets, Grieg was well aware that such translations were often inadequate. As he writes, “unfortunately, in my efforts to obtain good translations I have often had bad luck.”

“It is true that the task presupposes a versatility rarely to be found, since the translator must at the same time be poet, linguist and musically knowledgeable. … If, however, a rhythmically bad translation is also unpoetic and banal, then the poet’s meaning is downright distorted, as is so often the case in the German, English and French translations of my songs. No wonder, then, that nobody takes pleasure in studying them.”

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa (The Mountain Maid), Op. 67 “At the Brook” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Bengt Forsberg, piano)

You soft-swirling brook, you soft-purling brook,

You lie here contented, so warm and clear.

You splash yourself clean; a sparkling, bright sheen,

And murm’ring, our stream over rock crowns that gleam.

In sunlight, your soft, glowing shimmer brings cheer.

Oh, here let me rest now, rest now!

You mild-splashing brook, you wild-splashing brook,

Through sun-brightened slopes, course your happy way!

Your dim, babbling sounds, hum click, clack in rounds,

Neath high-arching leaves, they their melodies weave,

Where long, drowsy shadows and coolness holds sway.

The air sets me dreaming, dreaming.

You shimmering brook, you glimmering brook,

Snug in your bed ’neath the moss-banks, you sing.

As daydreams fleet by, and musing, you sigh,

Your whisperings increase in this vast utter peace,

A balm for all heartache, oh, soothe this yearning!

It’s here I’ll remember, remember.

Oh, quickening brook, oh, flickering brook

What thoughts on your way do you thus intone,

As through open space through bright fields you race,

Lost in deep terrain, to appear again?

Have ever you seen one as I, so alone?

Ah, here I’ll forget now, forget now.

You light-tripping brook, you bright-tripping brook,

You dawdle and play in the grove on your way.

And smile towards the sun, and chirp as you run,

And laugh in the shade, as you dart through the glade.

No song sing of me, my poor thoughts to betray!

Oh, let me now slumber, slumber!

(Translation by Rolf Kr. Stang)

Arne Garborg (1851-1924) was born near Stavanger, and although he never graduated from university, he was making his living as a teacher, journalist, writer, and linguist. The poet was deeply concerned with various aspects of contemporary life and submerged in the ever-changing attitudes in Norwegian culture.

Grieg was immediately attracted to Garborg’s well-developed sense of literary values, and Garborg was delighted that the composer had found his verses musically usable. As a scholar writes, “By carrying the poem’s virtues—the lyrical depiction of nature, of mystical worlds, and of the lives and emotions of ordinary people—over into the musical setting, text and music enter a symbiotic relationship like never before in Grieg’s oeuvre.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Edvard Grieg: Haugtussa, Op. 67 No. 8 (At the Brook) arr. cello and piano (Ramón Jaffé, cello; Andreas Frolich, piano)