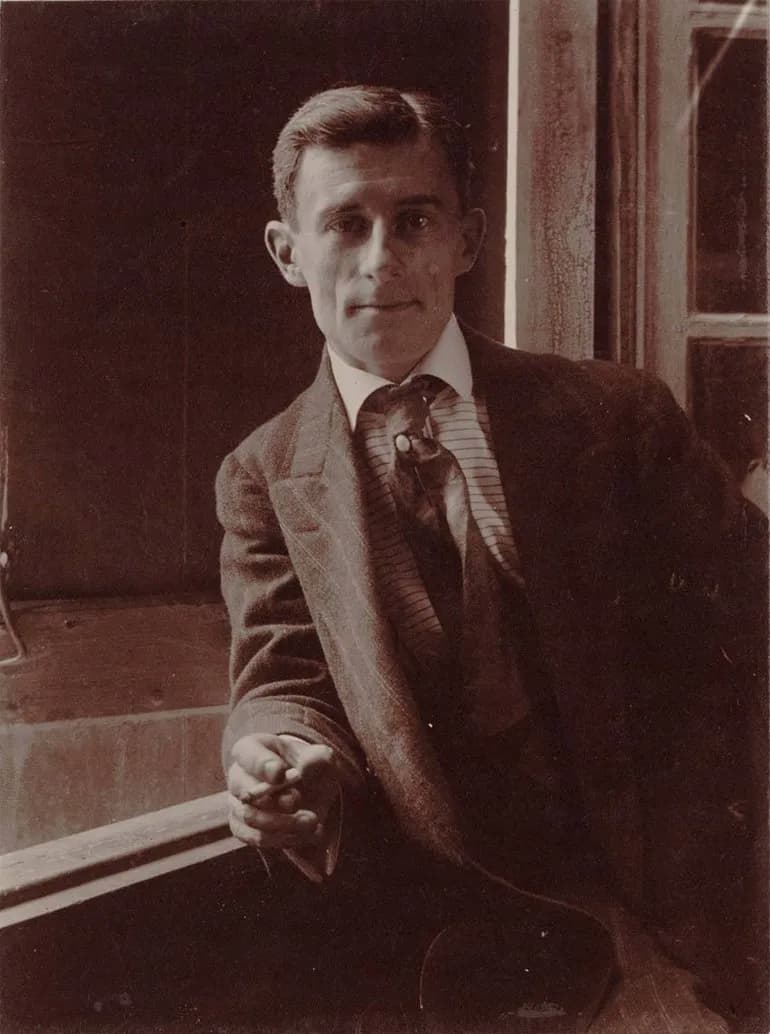

Sometimes, it’s tempting to think of Ludwig van Beethoven as someone who just emerged from a god’s forehead, a la Athena.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven

But in reality, Beethoven came from a very human family, just like everyone else – and a deeply dysfunctional one, at that.

Today, we’re looking at Beethoven’s family, and especially his fraught relationships with his two brothers, Kaspar van Beethoven and Johann van Beethoven.

The Beethoven Kids’ Parents

Bonn court musician Johann van Beethoven and the widow Maria Magdalena Keverich Leym were married in November 1767.

The Beethoven side of the family wasn’t keen on Maria Magdalena; they felt her social status was too low. But the marriage went ahead anyway.

The couple had seven children. Three survived into adulthood.

Ludwig was the eldest, born in December 1770. Kaspar Anton Carl van Beethoven followed in 1774, and Nicolaus Johann van Beethoven in 1776.

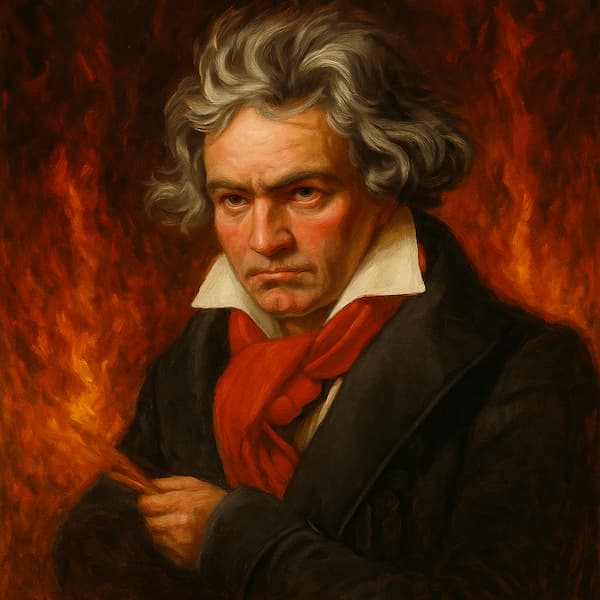

Beethoven’s Tragic Childhood

Beethoven’s parents

Ludwig showed musical talent early. Unfortunately, Johann was an abusive teacher who beat Ludwig or locked him in the cellar if he didn’t play something correctly.

Johann also was wrestling with alcoholism that became worse through the 1780s, and of course, that made everything worse.

In 1787, Ludwig finally escaped the household and set out for Vienna to study or start his career. But that same year, Maria Magdalena fell ill with tuberculosis. Ludwig came home to Bonn – a generous patroness paid for his return – and his mother died soon after. Ludwig was just sixteen.

Predictably, the stress and the grief worsened Johann’s addiction. Things got so bad that when Ludwig turned 18, he petitioned the authorities to have half of his father’s paycheck rerouted to him, so that it wouldn’t be spent on alcohol.

In 1792, Ludwig escaped again, knowing he needed to make a living and that Vienna would be the best place for a musician to try to do so. He was 21. Weeks after his departure, his father died.

Kaspar von Beethoven

Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven, Beethoven’s brother

Kaspar, the brother closest to Ludwig in age, came to Vienna the year he turned twenty.

He taught piano part-time, coasting off Ludwig’s reputation since he wasn’t particularly musically gifted, and also took a government job in finance.

He also worked as Beethoven’s secretary, serving as a liaison between Ludwig and his publishers. He was terrible at this job. At one point, he offered one set of pieces to one publisher when Ludwig offered the same set to another publisher. Their frustration with each other grew so heated that they eventually got into a physical fight.

Eventually, Kaspar moved on to another job. (Wise.)

Kaspar’s Disastrous Marriage

In 1806, Kaspar married a younger woman named Johanna, who was six months pregnant with Kaspar’s baby.

Ludwig looked down on her and gave her the catty nickname “The Queen of the Night” after the villainous character in Mozart’s opera.

The Magic Flute – Queen of the Night aria (Mozart; Diana Damrau, The Royal Opera)

In July 1811, Johanna became involved in a scheme to steal an extremely expensive pearl necklace. She was set to arrange a sale of the necklace and receive a commission. But she staged a robbery and framed her maid for the crime.

Soon, the maid was released for lack of evidence, and the case stalled. But then Johanna made the mystifying decision to wear the expensive pearl necklace in public, and she was caught.

She was nearly imprisoned under very harsh conditions for a year, but Kaspar was able to negotiate a sentence of time served.

In 1812, Kaspar developed tuberculosis, the same illness that killed their mother, and he died in 1815. Toward the end of his life, he and Johanna depended on Ludwig’s financial support.

Karl van Beethoven, Beethoven’s nephew

The day before his death, Karl Sr. appointed both Johanna and Ludwig co-guardians of his son six-year-old Karl, Jr., writing, “The best of harmony does not exist between my brother and my wife. God permit them to be harmonious for the sake of the child’s welfare. This is the last wish of the dying husband and father.”

As you can imagine, the last wish was not fulfilled, and Johanna and Ludwig got into a major court battle. But that’s a long story of its own.

Johann van Beethoven, Pharmacist

Nikolaus Johann van Beethoven

Ludwig’s other brother, Nikolaus Johann van Beethoven, became a pharmacist.

In 1795, the year he turned nineteen, he also moved to Vienna to be with his older brothers. Around this time, he also started going by the name Johann in honor of his father. Some historians have suggested that this was triggering to Ludwig, who presumably didn’t want any additional reminders of the childhood abuse he’d suffered.

In 1808 Johann moved to Linz to start his own pharmacy. He was no business genius, and the pharmacy would have gone under pretty quickly, except for the fact that Napoleon invaded Austria in 1809. It turns out that French forces needed medicine, and by sheer dumb luck, Johann was in a position to prosper. That said, his local reputation deteriorated, as those around him viewed him as a bit of a traitor for aiding the French and cashing in on invasion.

Johann van Beethoven, Landowner

In 1812, Johann got married. His new wife was his former housekeeper. Ludwig was appalled and tried to stop the wedding, but to no avail. In the end, it was never a particularly happy marriage. They never had children.

In 1819, Johann had earned enough money to buy an estate. There’s a famous story that after the sale was closed, Johann signed a letter to Ludwig with “From your brother Johann, landowner.” Ludwig, unimpressed, responded with the signature, “From your brother Ludwig, brain owner.”

Despite any prickliness between the two, in late 1826, Ludwig came to visit Johann’s estate, and he brought Karl Jr. While there, Ludwig wrote the last music he’d ever write: a replacement finale for his String Quartet Op. 130, since his publishers didn’t like the Grosse Fugue.

Solem Quartet: Beethoven op.130

Ludwig died in March 1827.

Johann had never been very interested in his brother’s music, but after his death, he took a new interest in the subject. He became famous for sitting in the front row at concerts and annoying people by yelling bravo. Johann van Beethoven died two decades later, in 1848.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter