The question as to what makes us human has been pondered for many thousands of years. While there are multiple theories, we can probably say that humans are unique. In fact, the very act of contemplating what makes us human is unique among all species on earth.

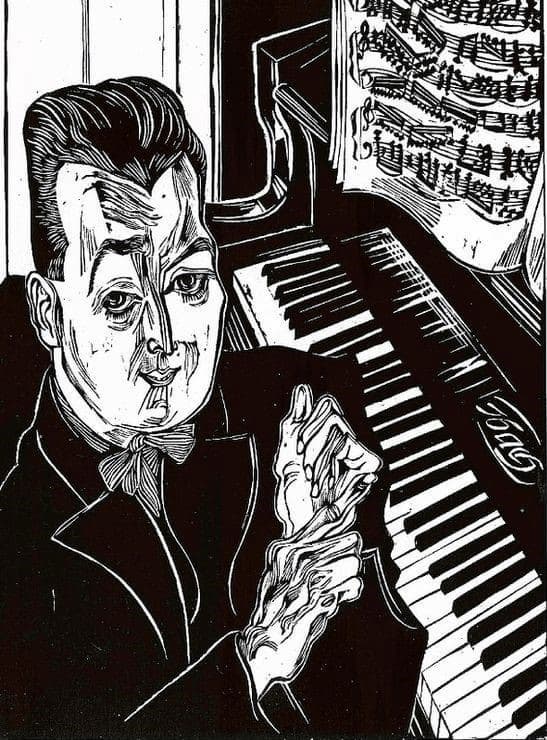

Erwin Schulhoff

Many characteristics have been used to describe the quality or the state of being human, including sympathetic, kind, benevolent, and human love and compassion towards each other. Humanity does imply a moral force, and it does carry notions of philanthropy and altruism. Common wisdom suggests that there is a sense of common humanity that unites people of all nations.

With crimes against humanity perpetrated on a daily basis, such flowery descriptions are, at best, sentiments of goodwill. As a philosopher writes, “the central feature of human existence has been the making of, threatening with, or use of weapons.” As such, definitions of humanity are better not left to politicians but explored in the different strands of the disciplines of the humanities and in the Art.

Erwin Schulhoff: Humanity, Op. 28, “Bagpipes” (Randi Stene, mezzo-soprano; Trondheim Symphony Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)

Erwin Schulhoff

The end of World War I in 1918 was one of bitter disillusionment. The world of the nineteenth century had ceased to exist, “slaughtered as it was in the trenches of the war.” People had gained a first impression of the potential for warlike violence causing unspeakable terror, and the arts simultaneously attempted to come to terms with unfathomable fear and an overbearing lust for life.

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was born in Prague of German descent. Like Kafka and Mahler, he was a German Jew growing up in a Czech cultural environment. A scholar writes, “Schulhoff took full advantage of his ‘outsider looking in’ status, and he was one of the earliest and most successful exponents of art music drawing on jazz.”

Schulhoff “refracted multiple approaches of his time,” but his artistic path was not shaped by musical events but by the First World War. He was conscripted into the Austrian Army and suffered a shrapnel wound to his hand and nervous shock. He also served on the Russian and other fronts throughout the war and “emerged disillusioned and angry.” And it was within that context that he composed his symphony for alto and orchestra entitled “Menschheit” (Humanity).

A bagpipe hums familiarly and sadly in the grove,

It calls full of lust from a dull valley.

The roses are bleeding heavily in the moonlight,

Enamoured June beetles flash through the scent.

The bagpipes fall silent in blue laurel darkness,

Another nightingale sings, it complains, it is silent.

The weak wind tells of whispers and rumours,

And we watch as the moon tilts higher and brighter.

A fountain calls to us, I listen to its noise:

It attracts me – like silver flashes the gravel

With clear water I can chat for a long, long time,

It seems to me that I never left the source.

The good bagpipes buzz through the bowers again,

And all the quiet noise is almost listening: listening!

The pipes hums and sobs full of old peasant faith,

The forest madness is water, wind – I’m intoxicated.

But again the distant noise surprises us:

How close it was! And the nightingale strikes again!

The flood escapes, gurgles in short whirlpools,

The wind encompasses us completely: now I’m afraid everywhere.

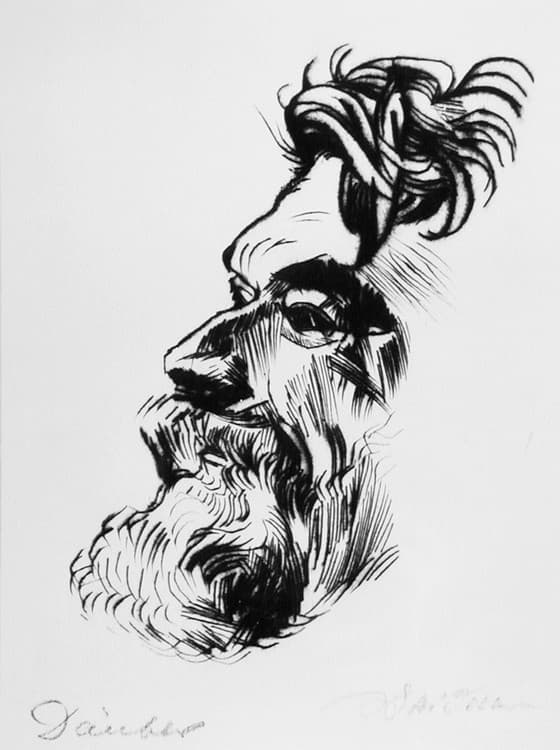

Portrait of the Poet Theodor Däubler

Erwin Schulhoff: Humanity, Op. 28, “Lame attempt” (Randi Stene, mezzo-soprano; Trondheim Symphony Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)

The moon roams through deserted alleys,

Its glow falls through pale panes.

I don’t want to stay in this alley,

I am tired of houses turning silent.

But what is moving on the terraces?

I imagine a curious happening

As if circles wanted to physically describe themselves,

I sense sounds without grasping them.

A white bird may well appear,

Almost like a dragon trying to rise,

But slowly bending down.

How blind and peculiar this lunar animal seems to me,

It knocks on windows, breaking the silence

And then lies dead in groves under figs.

Erwin Schulhoff: Humanity, Op. 28, “Frequently” (Randi Stene, mezzo-soprano; Trondheim Symphony Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)

Schulhoff turned to the poetic vision of Theodor Däubler, a German-language poet born in Austro-Hungary Trieste, currently in Italy. Like Schulhoff, he tapped into various sources of inspiration, including Classical and Romantic aesthetics, yet he is probably best remembered for his influence and enthusiasm for Expressionist painting and sculpture.

George Grosz

Däubler presents poetic visions of extraordinary vitality in sweeping, hyperbolic language that sometimes “borders on the bizarre or grotesque.” He was the author of more than twenty books of poetry, prose, and art criticism, and he was essentially attempting to reconcile notions of tradition across a Futurist and Classical framework.

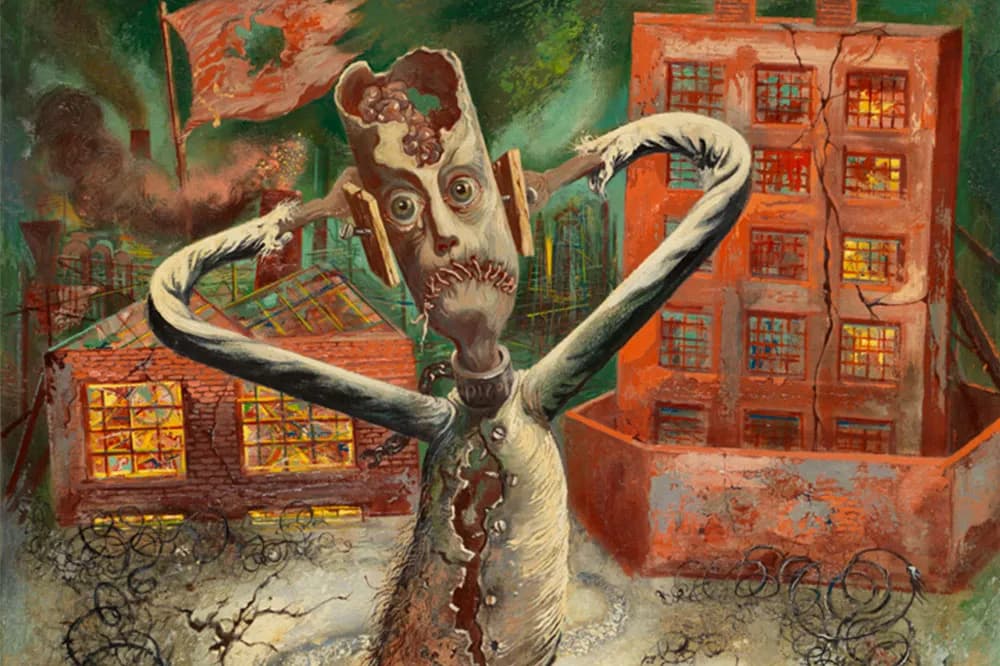

Däubler developed a close relationship with the Berlin-based artist George Grosz, lending his poetry a dense visuality, with images and words interacting. An art historian writes, “Däubler needs the visual arts: their history and even more their next present, which he recognizes as the necessary correlate of his own will. It is part of his creative idiosyncrasy as a poet, he productively evaluates art impressions in a completely new way.”

The first star is in the sky,

The beings think God is the Lord,

And boats leave speechless,

A light appears in my house.

The waves rise white,

It all seems sacred to me.

What moves into me in a meaningful way?

You shouldn’t always be sad.

Erwin Schulhoff: Humanity, Op. 28, “Twilight” (Randi Stene, mezzo-soprano; Trondheim Symphony Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)

The Grey Man Dances (detail; 1949), George Grosz Estate. © Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, NJ/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Däubler’s vision of art is not analytical, formal, or psychological, as it is not incorporated into any aesthetic category. According to an art critic, “It is an attempt to translate the visual experience directly into the language to test the violent reflection of his poetic receptivity in a vivid impression.”

In the final song, “Insight,” we find the main statement of the cycle. Humanity is at an end, and there is no more hope. Neither religion nor the Enlightenment can prevent the horrors from occurring. For Schulhoff, WWI was the final expulsion of humanity from paradise, including the paradise of hope.

As he writes in his diary, “it is nothing less than a flood, a destructive force threatening to destroy the entire culture of humanity. I can only place the years 1914, 1915, 1916 on humanity’s lowest rank; they make a mockery of the 20th century.’

Don’t cry, Virgin Mary,

You can’t save people.

Rock your child on your knee,

As if we still had happiness.

But we are left to our own devices

And teach ourselves to hate the Saviour.

You are pale, Virgin Mary.

Even paler than that day,

Since they spit on the Lord God,

Because now the only question is:

How would salvation be without?

The painful increase of joy?

We pity you, poor Virgin Mary.

You can’t cover yourself up anymore.

You’ve never been so visible.

Consolation shall be fulfilled in you.

You cannot get rid of the poor,

But you will grace them with humility.

It is music of surging and excessive passion, alternating between comfort and melancholy. To a critic, “melancholy never sounded as opulent as it does here; never before or since was suffering so luxuriously garnished.” The verses are clearly defeatist, and for Schulhoff prophetic as his music was subsequently labelled degenerate by the Nazi regime. Schulhoff was arrested and imprisoned, and he died in a Nazi prison camp from tuberculosis in 1942. Fast-forward to 2023, and humanity still rejoices and celebrates its inhumanity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Erwin Schulhoff: Humanity, Op. 28, “Insight” (Randi Stene, mezzo-soprano; Trondheim Symphony Orchestra; Muhai Tang, cond.)