Flor Alpaerts: James Ensor Suite

The Belgian artist and printmaker James Baron Ensor (1860–1949) left school at age 15 to start his artistic training and two years later entered the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. His early work was largely rejected in his own time for being scandalous, as critics did not see his innovative side, and in turn, he rejected the judgment of his critics. By the turn of the century, his paintings were being collected by the royal Belgian collections, and by 1920, he was the subject of major exhibitions.

Several common themes show up in his art: skeletons (including a self-portrait of himself as a skeleton painter), masks that hide the faces that they cover, and references to older works by other artists. We’ll see all of these themes in the pictures below.

Ensor: Self-portrait, 1890 (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen)

The Belgian conductor, composer, and teacher Flor Alpaerts (1876–1954) wrote his 4-movement suite in 1931 based on paintings by Ensor, and it’s considered one of his finest works. He was the leading Flemish impressionist before moving into an expressionist and then neo-classical style. What is a rarity in music based on artistic sources was the fact that Alpaerts’ James Ensor-suite was composed during Ensor’s lifetime.

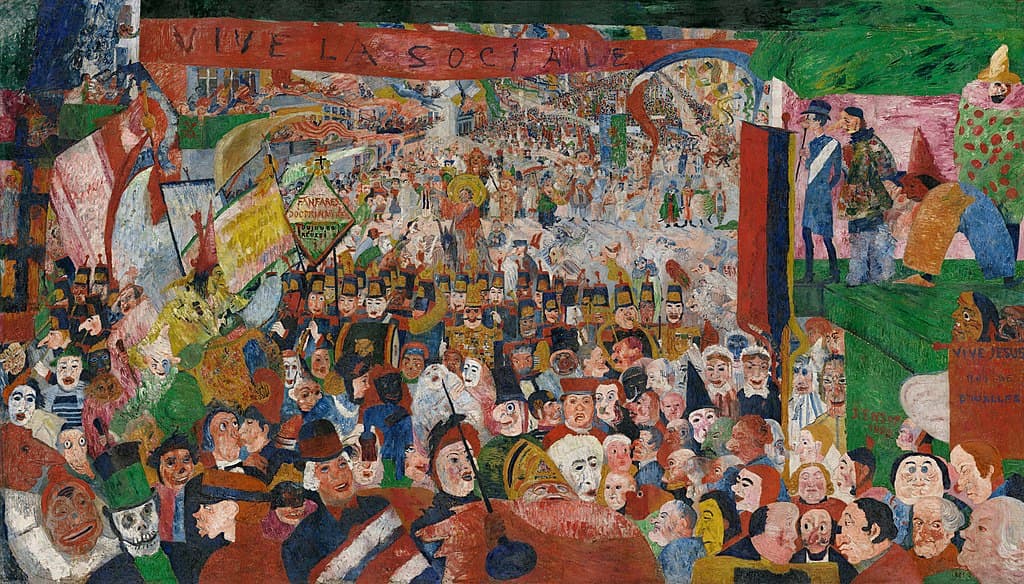

The suite opens with one of Ensor’s most controversial paintings, Christus’ intocht te Brussel (The Entry of Christ into Brussels). The painting is enormous, 252.7 cm × 430.5 cm (99.5 in × 169.5 in), and is a post-impressionist / pre-Expressionist work completed in 1888. The canvas was so big that Ensor could only work on it in sections – nailing the part he was working on to the wall and letting the rest drape on the floor. Christ does not lead the parade but is lost in the center, findable only by his golden halo, red cloak, and the ears of the donkey he’s riding on.

None of the figures around him pay him the least attention. It’s carnival time, and he’s surrounded by grotesque clowns, a marching band in uniform, and people wearing masks who are all part of the parade. Over the street is a banner reading ‘Vive la Sociale’ and, at the right, another banner reads ‘Vive Jesus Roi de Bruxelles.’

Ensor: Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889, 1888 (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum)

Flor Alpaerts: James Ensor Suite – I. Christus’ intocht te Brussel (The Entry of Christ into Brussels) (Flemish Radio Orchestra; Michel Tabachnik, cond.)

As we saw in the painting above, skeletons appear in Ensor’s art, and none so prominent as in his 1891 painting Gemaskerde Geraamten in Betwisting om een Gehangene (Masked Skeletons Fighting Over a Hanged Man). Two masked skeletons in women’s clothing fight with a curtain rod and a broom. Between them, the hanged man carries the sign ‘Civet’, not meaning the Asian mammal, but a southern French/Spanish meat stew made with chocolate (to replace the original ingredient of blood). In the doorways behind our combatants are interested onlookers, with their own masks and with knives and razors. The work’s meaning is unclear today: it could be the artist in the middle, being fought over by his wife and mistress, or the artist in the middle between the critics who love him and those who hate him. The figures in the doorways exhibit many different emotions on their faces, from anger to curiosity.

Ensor: Gemaskerde Geraamten in Betwisting om een Gehangene, 1891 (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp)

Flor Alpaerts: James Ensor Suite – II. Gemaskerde Geraamten in Betwisting om een Gehangene (Skeletons Fighting for the Body of a hanged man) (Flemish Radio Orchestra; Michel Tabachnik, cond.)

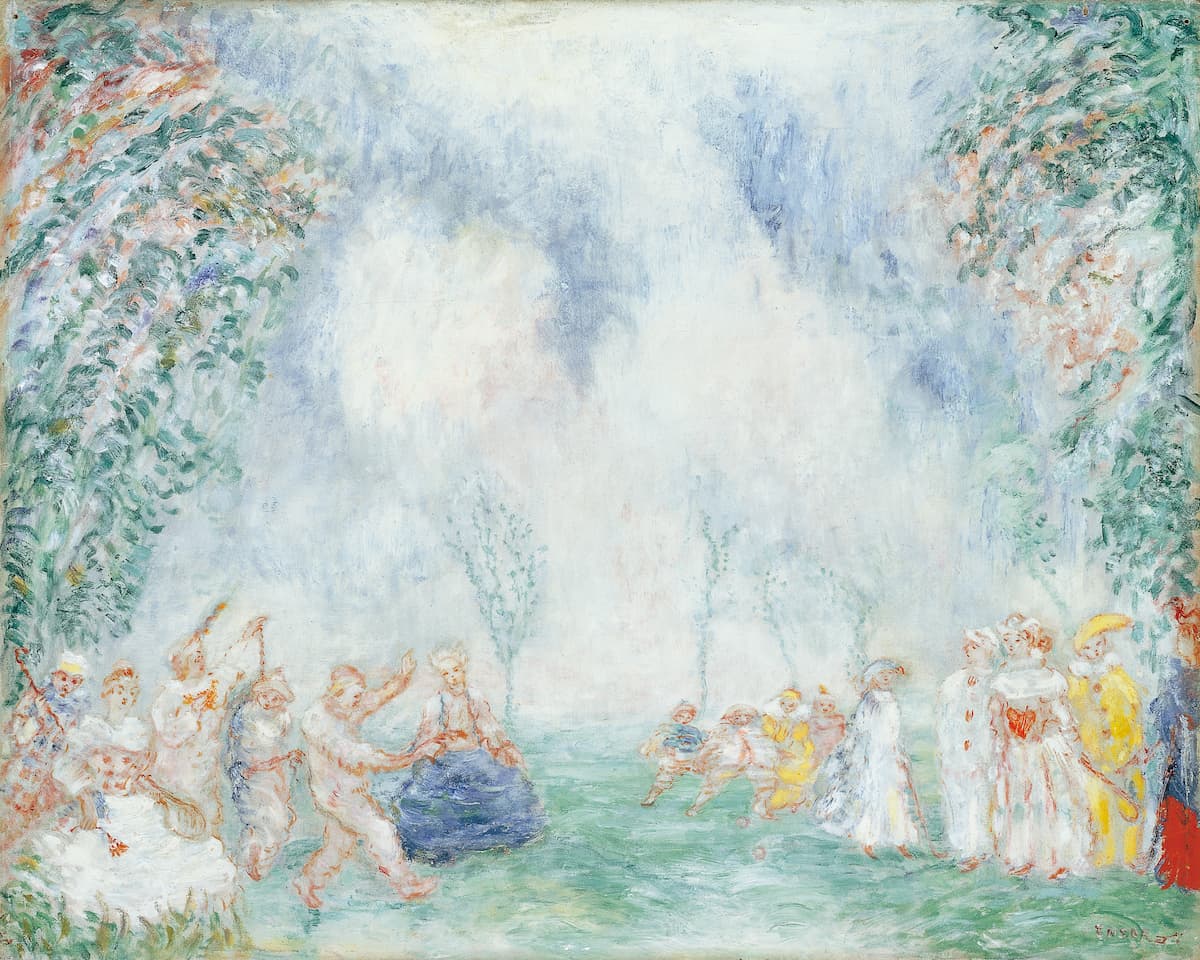

Two different works of art, one painting, and one an etching, could be the inspiration for the next movement. De Tuin der Liefde (The Garden of Love) as an oil painting dates from around 1925. More masks, but now as from a masked ball with a yellow Pierrot on the right standing next to the Queen of Heart. There is much here that reflects Ensor’s study of Watteau’s works, and it seems to be very far away from the macabre humor we found in the earlier Ensor works. Ensor returned to the idea of the ‘garden of love’ many times and inscribed one of them as being ‘in remembrance of Verlaine’.

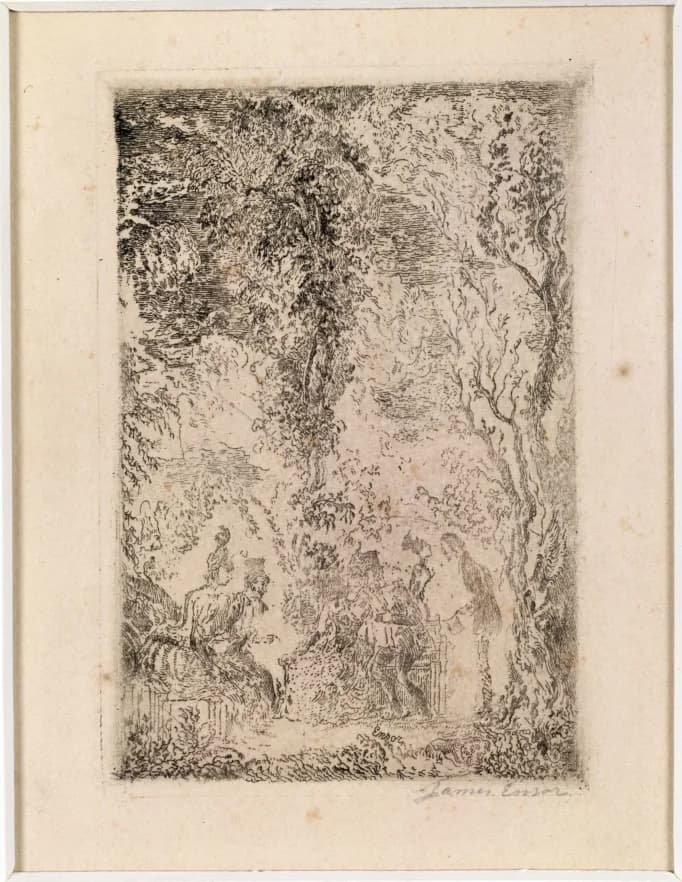

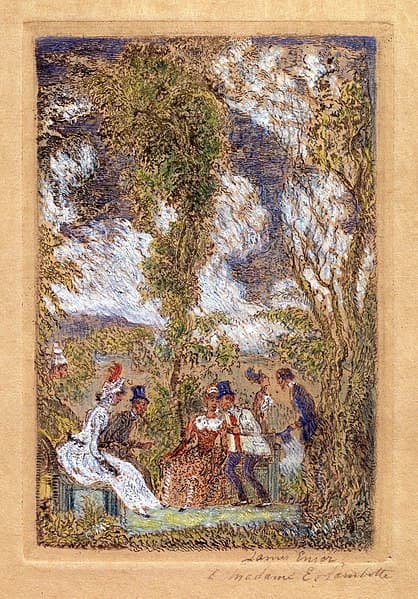

Ensor also did a series of etchings called Minnetuin (The Garden of Love) in 1888. Some of these were completed in black and white, and others were coloured. In Minnetuin, we again have figures in a garden but in daily clothes, not as costumed figures. The setting of the figures in a garden filled with trees is reminiscent of another Watteau picture, Les Jaloux, which is lost and known only in an engraving by Gerard Scotin.

James Ensor: Jardin d’amour, ca 1925 (Madrid, Carmen Thyssen Collection)

James Ensor: Minnetuin (Garden of Love) – uncoloured, 1888 (Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent)

James Ensor: Minnetuin (Garden of Love) – coloured, 1888 (Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent)

Gerard Scotin after Watteau: Les Jaloux / Invidiosi (National Galleries of Scotland)

Flor Alpaerts: James Ensor Suite – III. De Tuin der Liefde (The Garden of Love) (Flemish Radio Orchestra; Michel Tabachnik, cond.)

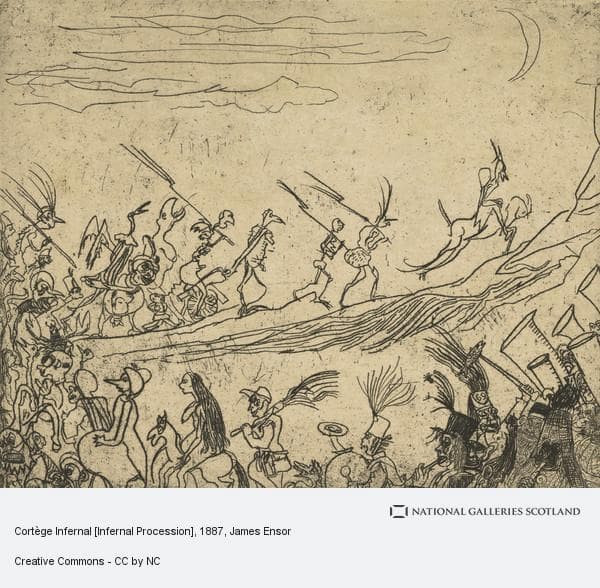

The work closes with a movement based on one of Ensor’s etchings from 1887, Cortège Infernal (Infernal Procession). We could be in the final movement of Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique in this picture of a horned rider on a fantastique horned beast, leading a procession of strange figures with animal-like features but holding human pitchforks. Some figures are skeletal, others have enormous heads, or are tiny in size. At the end of the procession is a ghostly band led by a drum major who’s caught a fish on his baton. It’s morbid and menacing and is very much in line with Ensor’s own perceptions of the social and political inhumanity around him.

Ensor: Corège infernal, 1887 (Edinburgh: Scottish National Gllery of Modern Art)

Flor Alpaerts: James Ensor Suite – IV. Helse Optocht – Sabbat (Infernal Cortege – Sabbath) (Flemish Radio Orchestra; Michel Tabachnik, cond.)

Alpaerts’ realization of Ensor’s various visions: impressionistic, expressionistic, satirical, or in a grim honour comes through clearly in the movements. The first movement’s sinister opening doesn’t bode well for the Christians of 1888 Brussels. The percussion in the second movement to depict the skeletons fighting is perfect and yet is a different sound than the movement and fury of the Infernal cortège of the last movement. The Garden of Love is calm and beautiful, with the twittering of birds in the trees and the woodwinds’ evocation of a beautiful day.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter