At the time of his death on 28 December 1937, Maurice Ravel was the most celebrated composer in France. For a number of scholars, however, the significance of his music and the nature of his artistic legacy remained elusive. And as we well know, Ravel had no intentions of disclosing his innermost thoughts and ideas to anyone.

Maurice Ravel, 1916

An attempt to probe the composer’s thoughts and ideas had taken place in 1928, instigated by the Aeolian company, a firm specialising in player pianos. The company inaugurated a series of Ravel recordings on specially perforated rolls, which would also contain autobiographical comments by the composer himself. The artistic director of the company, Monsieur Henri Dubois had asked Ravel to participate, but the composer was uneasy about writing down his own commentary.

As such, Ravel turned to Roland-Manuel to act as his secretary in an interview. Dubois rejected the interview format, but it was agreed that Ravel would dictate an autobiographical statement which would later be edited. Ravel never edited his notes and completely withdrew from the project, but Une Esquisse autobiographique de Maurice Ravel, based on Roland-Manuel’s uncorrected draft, was published nevertheless in 1938.

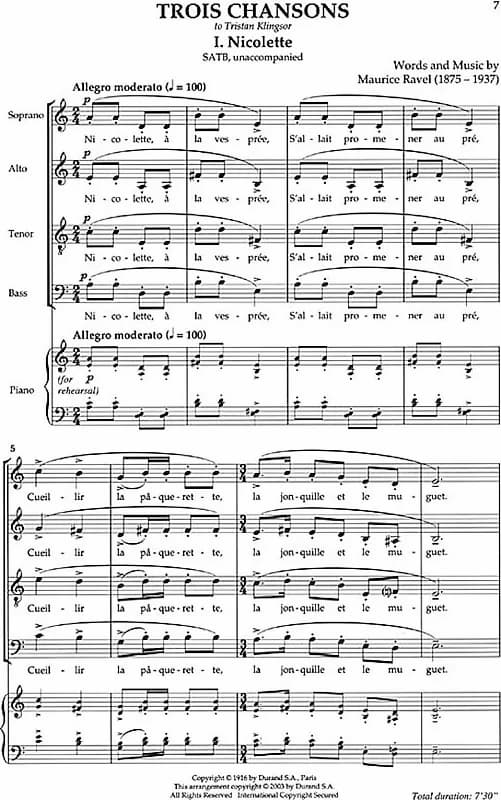

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons, “Nicolette” (North German Figural Choir; Jorg Straube, cond.)

Ravel’s Autobiographical Sketch concludes with a distinct statement on music and his personal aesthetic. According to the draft, Ravel said “I have never felt the need to formulate, either for the benefit of others or for myself, the principles of my aesthetic. If I were called upon to do so, I would ask to be allowed to identify myself with the simple pronouncements made by Mozart on this subject. He confined himself to saying that there is nothing that music cannot undertake to do, or dare, or portray, provided it continues to charm and always remains music.”

Ravel’s sketch reveals as much as it conceals. As he writes, “At the beginning of 1915, I enlisted with the army and so my musical activities were interrupted until 1917, when I was discharged.” He doesn’t tell us that he made several attempts to join the troops at the front but that he was repeatedly turned down on medical grounds. Determined to fight for his country, Ravel took daily driving lessons in hopes of joining a supply department. He did pass the driving test and was posted to the combat sector around Verdun as a truck driver.

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons, “Nicolette”

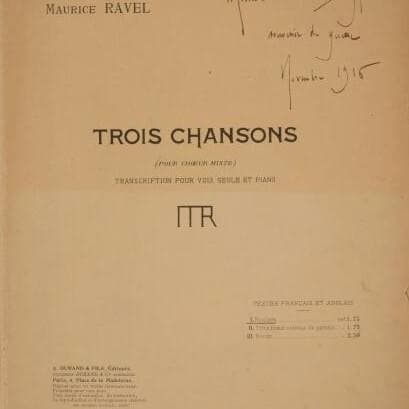

His “Autobiographical Sketch” contains a meticulous catalogue of his work, however, the Trois chansons for mixed choir a capella are omitted for some reason. Ravel had begun to draft the work while waiting to join the army in December 1914, and he reacted to the horrors of war with his own lyrics and music. “The nightmare,” he writes, “is too horrible. I think that at any moment, I shall go mad or lose my mind.”

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons, “Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis” (North German Figural Choir; Jorg Straube, cond.)

For some commentators, the Trois chansons represent one of Ravel’s subtle patriotic gestures, which were always devoid of crude chauvinism, as he resolutely refused to join a group whose aim was to ban from France all music composed in the enemy countries. To be sure, the common denominator in all three songs is the theme of loss, but it is not handled without considerable humour and irony.

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons

“Nicolette” is a capricious French version of “Little Red Riding Hood.” While strolling in the meadows near her village, the girl first meets the big bad wolf but won’t accompany him to her grandmother’s. Next, a handsome page proposes marriage, which she finds difficult to reject. In the end, however, she loses her innocence to an older gentleman offering her plenty of gold. The initial musical theme is followed by three variations, one for each character, and the same melody sounds with a different harmonic background.

“Trois beaux oiseaux du Paradis” clearly references the war as three beautiful birds from paradise call on a young woman. Their respective plumage is in the colours of the tricolour, and they bring news that her lover has been killed in the war. This chanson is “an exquisite ballad full of tenderness.”

“Ronde” depicts a scene in a village of Green, with old people warning the young against entering the enchanted forest. Ravel invents an impressive catalogue of monsters and gnomes, but as the young people have received a modern education, they reject the warnings. Here, as in the previous chansons, Ravel’s musical language borrowed musical devices from the fifteenth century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons, “Ronde” (North German Figural Choir; Jorg Straube, cond.)