There’s something special about piano trios. Perhaps the combination of violin, cello, and piano makes the perfect pocket ensemble. They’re not as complex as string quartets, and the addition of the strings makes an ensemble that embraces the top and the bottom of the piano’s range.

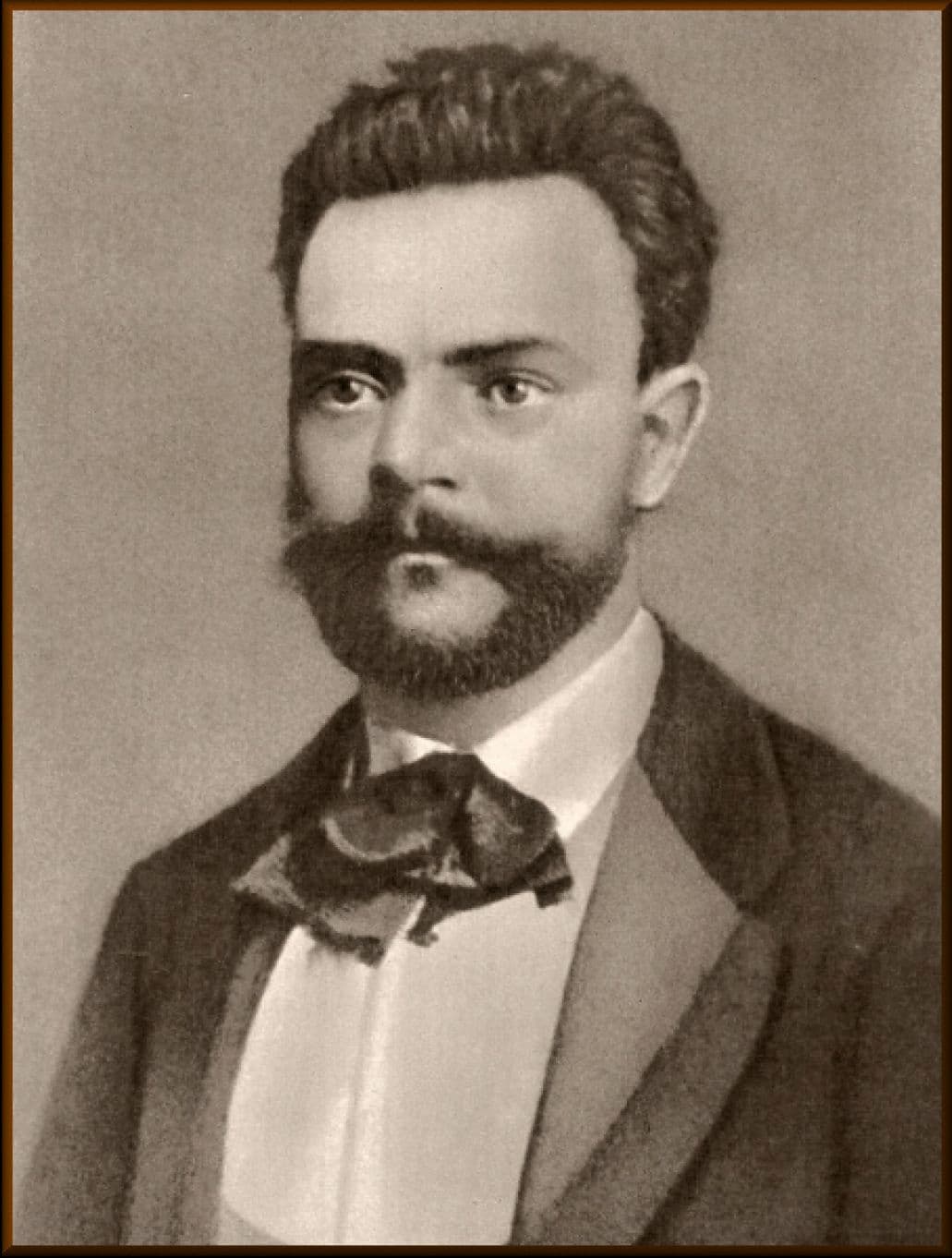

Dvořák in 1870

Between 1885 and 1891, Dvořák wrote 4 piano trios, 2 piano quartets, and 2 piano quintets. Piano Trio No. 3 in F minor, written in 1883, was written twice, with the second effort seeing the reversal of the two middle movements. It’s not the optimistic Dvořák we’re familiar with from his compositions from the later 1890s, such as his American Quartet and his 9th symphony, From the New World. This is Dvořák a year after his mother died, and at a time when he’s facing life-changing decisions of whether to stay in the relative backwater of Prague or to strike out Vienna where life would be much more challenging.

His third piano trio is darker and more dramatic, and the use of native folk music is toned down. The drama is present from the beginning, with the violin and cello in octaves before the piano enters. The piano entrance is the signal for a heightened dramatic feeling, full of impassioned statements. A lyrical cello melody calms the emotions and it is in the development section we can best see his influences: it is Beethovinian in its complex changes of mood and key and Brahmsian in its texture and melodic invention.

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio No. 3, Op. 65 – I. Allegro ma non troppo

After his time in New York at the National Conservatory, Dvořák spent a summer in the Bohemian community of Spillville, Iowa, a kind of Czech retreat in middle America. One result of his stay in 1893 was the Sonatina, Op. 100.

Boris Chaliapin: Fritz Kreisler, 1943 (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the artist)

The sound of this chamber work, written for violin and piano, is much simpler than we heard in Piano Trio No. 3. The work was dedicated to ‘my children’ and its first performers were his fifteen-year-old daughter Otilká (piano) and ten-year-old son Toník (violin). When the work was published by Simrock in 1894, Dvořák told his publisher that although the work was intended for young people, ‘grown-ups, too, may not be unwilling to amuse themselves with it’.

The second movement Larghetto brings in the ‘American’ sound that is so familiar from Dvořák’s other pieces written during his American sojourn. The story is that ‘Dvořák is said to have heard and sketched on his shirtsleeve the native American opening theme of the ternary Larghetto (G minor) during a visit to Minnehaha Falls, Minnesota in April 1893’. The overall mood harks back to Dvořák’s writing in the mid-1880s, a decade earlier, but there’s light in the darkness, with a major-key dance-like melody appearing in the middle. The end of the movement gives us a new harmonization of the opening melodies and it all just seems to become more beautiful.

Antonín Dvořák Sonatina, Op, 100 – II. Larghetto

The Larghetto was a favourite of the virtuoso violinist Fritz Kreisler and was a part of the extensive arrangements he did of other composers’ works to augment his own miniatures that he used for encores on his recitals. Following Dvořák’s death, Kreisler made a violin and piano arrangement of his Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7, much to the financial relief of Dvořák’s widow. In 1914, Kreisler made arrangements of more of Dvořák’s pieces, including the Larghetto above, titled as Indian Lament; the Largo from Symphony No. 9, titled as Negro Spiritual Melody; and a set of Slavische Tanzweizen, that were made from Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, Op. 46 and 72. The Slavic Dance arrangements were where Kreisler let his compositional imagination run away with him, changing the original keys, adding advanced violin techniques (such as double stopping) so it sounds like 2 violins are playing, and even putting two different dances together, as he does in the Op. 46, No. 2.

Shaham Erez Wallfisch Trio

Kreisler starts by changing the key, so that he begins in G minor (instead of the original E minor), next he mixes the melancholic opening melody with a much more energetic dance episode. When the original theme returns, he’s back to Dvořák’s original key of E minor. This then leads ‘to a rhythmic episode extracted from a completely different dance – Op.72 No.1’. To make sure you know this wasn’t an error, Kreisler brings it back again in the conclusion.

Antonín Dvořák: Slavonic Dances, arr. by Fritz Kreisler, Dance, Op. 46, No. 2

This recording was made by the Shaham Erez Wallfisch Trio, made up of Israeli violinist Hagai Shaham, British cellist Raphael Wallfisch, and Arnon Erez, longtime accompanist of Hagai Shaham. Both Shaham and Erez are professors of music at the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music at Tel Aviv University.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter