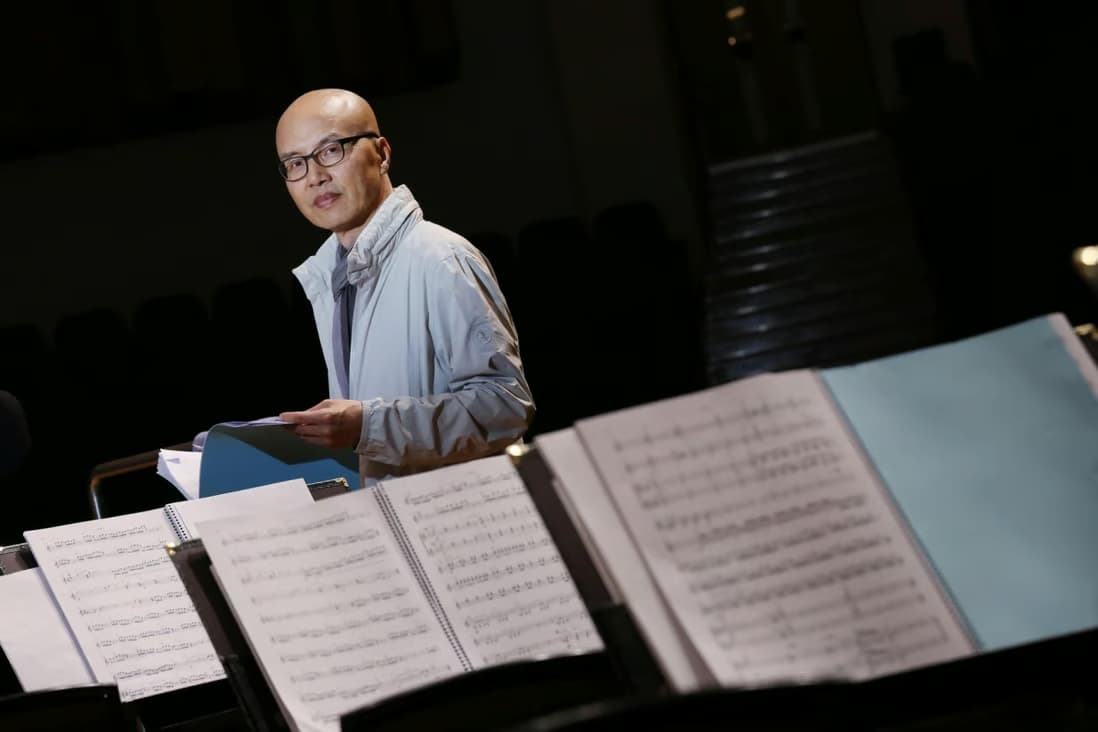

Based between Beijing and Paris, Qigang Chen’s music has been praised for achieving a ‘sustained dialogue between Chinese and Western classical and cultural traditions’ (The Guardian), drawing inspiration from both the music of his native China and the European classical tradition.

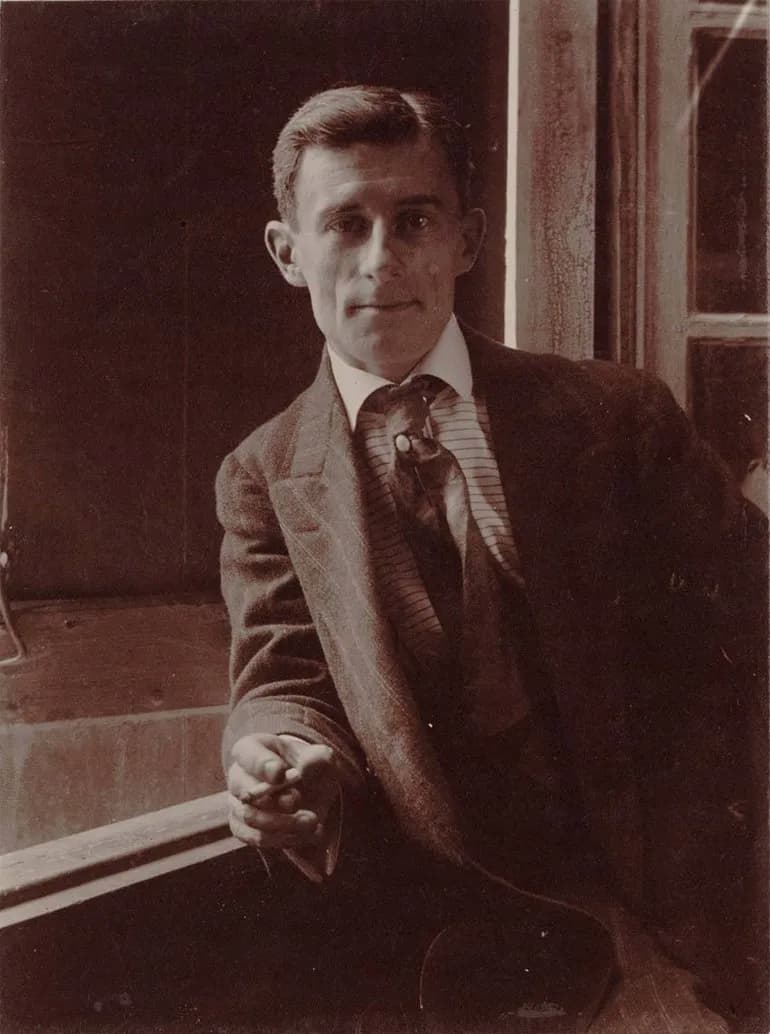

Qigang Chen © Nora Tam/South China Morning Post

Living through the 1966 Cultural Revolution, Chen’s studies at Beijing’s Central Conservatory of Music were cut short when he was confined for three years to undergo ‘ideological re-education’ while still only a teenager. There was considerable pressure for him to abandon his studies, but he pursued his love of composition relentlessly and in 1977 was accepted to study full-time at the Conservatory.

It was in 1983 that Chen travelled to Paris where he studied with Olivier Messiaen, who picked up on Chen’s talent and encouraged him to further develop his style, which blended elements of Chinese and European classical music together.

Chen’s works are regularly performed around the world. He has received commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation, Radio France, Stuttgart RSO, and Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, among others, and was the Director of Music for the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The music of Qigang Chen is incredibly varied, often travelling to extreme ends of the emotional landscape. It’s not uncommon to be immersed in a meditative, expansive musical atmosphere that suddenly gives way to a hard-edged modernist scherzo. He often draws on inspirations from Chinese music – be it certain scales, modes, or specific folk melodies – and uses these to craft a wholly unique style, a meeting point between two different musical worlds.

If you are unfamiliar with his output, here are three pieces to get you started.

Er Huang (2009)

Er Huang is a concerto for piano and large orchestra, premiered by Lang Lang and the Juilliard Orchestra under Michael Tilson Thomas at Carnegie Hall. Much of the source material was drawn from traditional Chinese operas, and their melodies are prominently featured throughout the work, either as literal transcriptions or as fleeting recollections.

The piece opens with the solo piano playing delicate chords, according to the score, ‘as if meditating’. These chords are echoed straight afterwards at a softer volume, and interestingly, Chen writes the echoed chords on two separate staves to the main piano line, to really emphasise the idea of them appearing ‘as if played by another pianist’.

Chen’s orchestration is incredibly subtle and delicate throughout much of this piece. The strings often shadow the piano’s pitches, creating a beautiful resonance that adds to the meditative atmosphere. Similarly, the celeste and vibraphone echo the piano’s tones, creating the illusion of sounds which drift ever farther away.

There is an innocence and deceptive simplicity to the opening section of this concerto which is reminiscent perhaps of Copland: wide open spaces, brilliantly handled harmony, and poignant orchestration.

As the music hots up and becomes more agitated, this simple harmony gives way to something more dense. We experience expansions and contractions of Chen’s harmonic language, this simplicity now being challenged by something altogether more hard-edged and frantic.

We travel between these two zones repeatedly during Er Huang, and the major climax of the piece – marked ‘luminous’ in the score – seems to fuse together the dual worlds of intensity and naivety in an incredibly expressive and expansive outburst. The piece ends with a section marked ‘nostalgic’, as if reminiscing about a distant dream.

Haochen ZHANG plays Qigang CHEN’s piano concerto “Er Huang” at Festival in Berlin

La joie de la souffrance (2017)

The joy of suffering, much like Er Huang, is very expansive, both timbrally and harmonically. A large-scale work for violin and orchestra, La joie de la souffrance comprises around ten sections, many of which have their own evocative subtitles.

From the opening of the piece, Chen’s carefully-chosen pentatonic scales and expressive appoggiatura portamenti in the solo violin part subtly conjure up the Chinese folk melodies that run throughout the work.

The suspended opening unfolds into a lullaby, a gently rocking accompaniment alternating with dreamlike sections suspended in midair. This gives way to a more scherzando section, the playful spiccato violin crackling and glistening over a relentless, unsettling march-like figure in the basses, cellos, and piano.

After a frantic climax, the calm atmosphere returns, marked in the score as ‘The beauty of suffering’, leading to ‘The beauty of solitude’, a poignant conversation between the violinist and a lone clarinet in the orchestra. The ‘solitary dance’ that follows features the same lullaby-like accompaniment but with a feeling of the earlier material being seen through a new lens.

Soon, the whole ensemble is encouraged to ‘Get caught up in the madness’, the playful skittishness returning, only now more sustained and active. This culminates with ‘Excruciating song’, an intense outpouring for both soloist and orchestra.

It is after this final climax that we hear the melody from earlier for the last time, a gentle reminiscence of the opening serenity, accompanied by fleeting images of the more frantic material, this time transformed into harmlessly floating scales.

It is here, at the end of the work, that we see the earlier difficulties in a new light, perhaps with a calm acceptance of sitting with whatever imperfections may remain.

Maxim Vengerov Plays Qigang CHEN’s “La joie de la souffrance” Violin Concerto

Jiang Tcheng Tse (江城子) (2017)

Set to text by Chinese poet Su Shi, Jiang Tcheng Tse is a piece for large orchestra and double chorus, along with a soprano soloist who sings in a traditional Chinese operatic style. Shi’s poem, the subject of the work, was written a decade after the death of his wife. In Chen’s own words, ‘Su Shi’s poems are generally known for their heroic quality, but he can also be extremely precise, earnest, subtle and delicate in expressing his feelings,’ and this contrast between the triumphant and intimate is explored here to great effect.

The piece opens with haunting atmospheric chords, out of which the soprano soloist gradually emerges, unfolding her long phrases in traditional Chinese operatic style while cushioned by warm chords in the accompanying choirs.

Sounds of Messiaen echo through the first climax, Chen’s luminous harmony and orchestration creating a dense, thick, rich sound.

Throughout the work we hear the soloist deliver several passages in what is marked in the score as ‘Chinese opera sprechgesang’, somewhere between speech and voice, the vocal contours naturally following the tones of the Chinese language.

There is a remarkable moment about two-thirds of the way in where the sprechgesang becomes ever more intense and hysterical, setting off a mighty climax across the whole orchestra and choir. Even during these moments of extreme intensity, Chen manages to sustain a dreamlike atmosphere in the music. There is always a warm bed of sound present, be it sostenuto muted strings or rich woodwinds. Yes, there are grandiose moments, but there the piece never loses its introspection; we witness the inner world of a voice forced to confront loss, loneliness, and grief in this incredibly moving work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Qigang Chen’s (Jiang Tcheng Tse 江城子) (2017) For Solo, Chorus & Orchestra