We should never forget that performing artists are essentially entertainers. And one of the biggest entertainers of his time was described as follows by the British magazine Belgravia in 1880:

Louis Jullien, 1812

“In the years 1847 the management of the Drury Lane Theater of London was assumed by a very eccentric and grotesque creature. It would be unfair to dismiss him as a mere charlatan however empirical his proceedings, he was his own chief dupe. He was crazily vain, very ignorant, extravagant, disorderly, tawdry, and vulgar but he was humane; he was ingenious after a fashion; he was enterprising beyond all reasonable bound, he possessed much natural wit; and he was animated by enthusiasm unquestionably genuine, for all its comical and crackbrained modes of expression. His name, it cannot yet be forgotten, was Louis Jullien.” His declared aim was “to ensure amusement as well as attempting instruction, by blending in the programmes the most sublime works with those of a lighter school.”

Louis Jullien: Prima Donna Waltz (arr. G.W.E. Friedrich) (Chestnut Brass Company)

Louis Jullien was born in Siseron on 23 April 1812, and he still carries the distinction of sporting a record 36 christened names, bestowed upon him by his 36 godfathers. He was considered a child prodigy and served in the army before entering the Paris Conservatoire. Bored by counterpoint, Jullien preferred the lively entertainments of dance music, and he carefully crafted his performing image by fighting three high-profile duels. Having conquered Paris, he left for England in 1838. Jullien eagerly immersed himself into popular British culture, and over his 19 years of entertaining activities he organized and participated in at least “24 promenade concert seasons in the London theatres, four summer seasons, notably of Monster Concerts at the Surrey Zoological Gardens, one and often two provincial tours each year, numerous engagements at balls and private social functions, a season of grand opera (1847), a highly successful tour, at the invitation of P.T. Barnum, of the USA (1853–4), where he gave 214 concerts in less than a year, a tour of the Netherlands (1857) and private novelty-seeking trips to the Continent.” His concerts were cleverly advertised and frequently included a tempting promise. “The program will include the Nightingale Waltzes, performed on the piccolo by M. Jullien. One of these most favored valses will be presented to each lady visiting the Dress Circle or Private Boxes.”

Louis Jullien: Le Rossignol, “Introduction – Waltz No. 1 à 3” (Hugo Reyne, flageolet/cond.; Orchestra of the 19th Century)

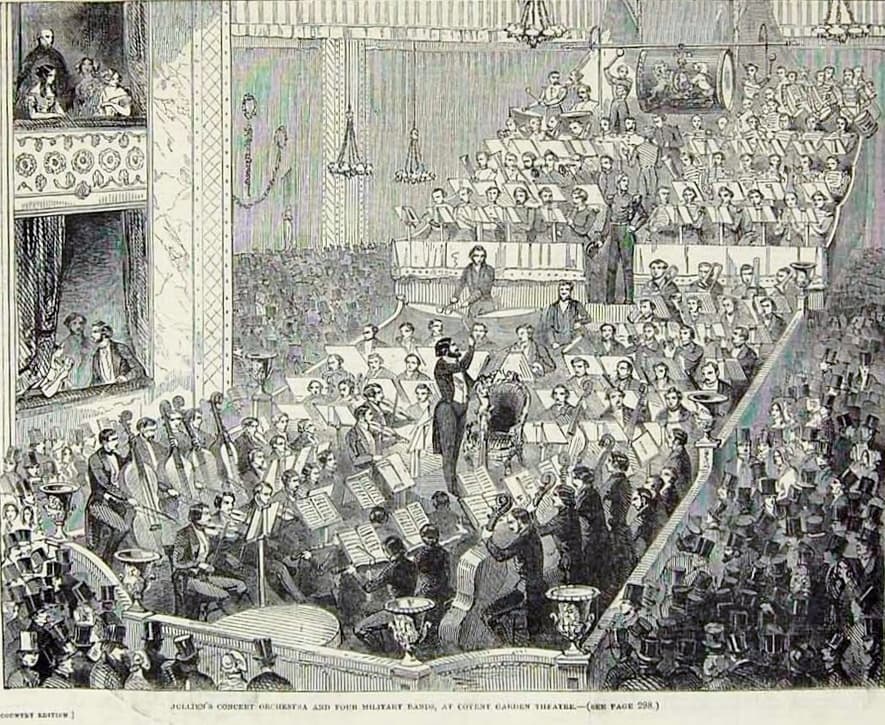

Louis Jullien conducting the ‘British Army Quadrille’ for orchestra and four military bands at Covent Garden Theatre (Illustrated London News, November 7, 1846)

As a conductor, Jullien possessed a certain instinct for new effects and combinations of sound, and “delighted in orchestral uproar of the prodigious sort.” It was reported that he “had a garden roller dragged over sheets of iron to simulate the roar of artillery; pans of red fire were lighted at intervals so that while the sense of hearing was assailed by the strangest clangor and hubbub, the faculties of eyes and of nose might be no less amazed by the flash and glare and the pungent fumes of nitrate of strontium.” On 24 February 1844 we found a detailed report of a typical Jullien concert in the Musical Examiner of London. “M. Jullien’s last musical invention, entitled A Grand Descriptive Fantasia of the Destruction of Pompeii was presented last week at the Covent Garden Theater. It is a compound of fiddling, red fire, bells, gunpowder, rattles, crackers, and chorus singing… There is a low grumbling to indicate the brewing eruption… and the joint production of the composer, carpenter, and fireworks-maker depicts the explosion of the crater, the falling of the temples, and the total destruction of the city… When all the gunpowder supplies were exhausted, the fantasia was considered at an end.”

Louis Jullien: Polka, “Echo du Mont Blanc” (Gabriel DiMartino, trumpet; Vince DiMartino, trumpet; Syracuse University Wind Ensemble; John M. Laverty, cond.)

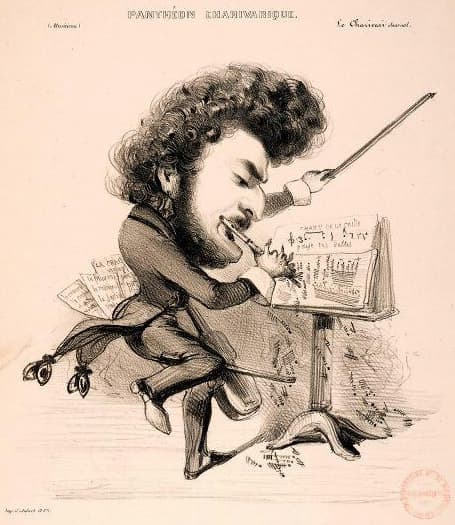

Caricature of Louis Jullien by painter Benjamin Roubaud

During one of his “monster concerts” at the Surrey Zoological Gardens in 1846, Jullien employed a number of four-pounder guns to accompany the national anthems. A critic reports, “The menagerie was all affright with the noise. The tropic tiger roared in unison thunder; the radical hyena grinned ghastly at the uproar; the bounding leopard leapt at his bars; the sovereign lion snuffed the noise and walked calmly up and down his den. Only the bear was apathetic. Neither Rossini nor Jullien affected him.”

Newspaper spoke pointedly about the “Bombardment of the Surrey Zoological Gardens.” Nevertheless, Louis Jullien was not all fire and brimstone, as he gave at least four complete Beethoven symphonies in his first London season. He did conduct Beethoven with a jeweled baton handed to him on a silver platter, and essentially invented the cult of the conductor. However, scholar suggest, “behind the pantomime and showmanship lay authority, and Jullien was able to attract the best of the London players into his orchestras and retained a team of first-class soloists over a number of years.” The Musical World cleverly summarized, “M. Jullien was undoubtedly the first who directed the attention of the multitude to the classical composers…he broke down the barriers and let in the crowd.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Louis Jullien: Le Rossignol, “Waltz 4-Coda” (Hugo Reyne, flageolet/cond.; Orchestra of the 19th Century)