One of the favourite activities of the 19th century was creating piano versions of works from other genres: symphonies reduced to the piano for two or four hands, favourite arias from favourite operas made into variation forms, songs with the words eliminated and all combined into two hands – all of these activities, and more, were part of the new piano products being produced daily.

The rise of the wealthy middle class and their search for culture were behind much of this new piano music. And, when famous virtuoso pianists, such as Liszt did it, it was like not only brought a bit of Liszt home but also made you a bit Lisztian at the same time.

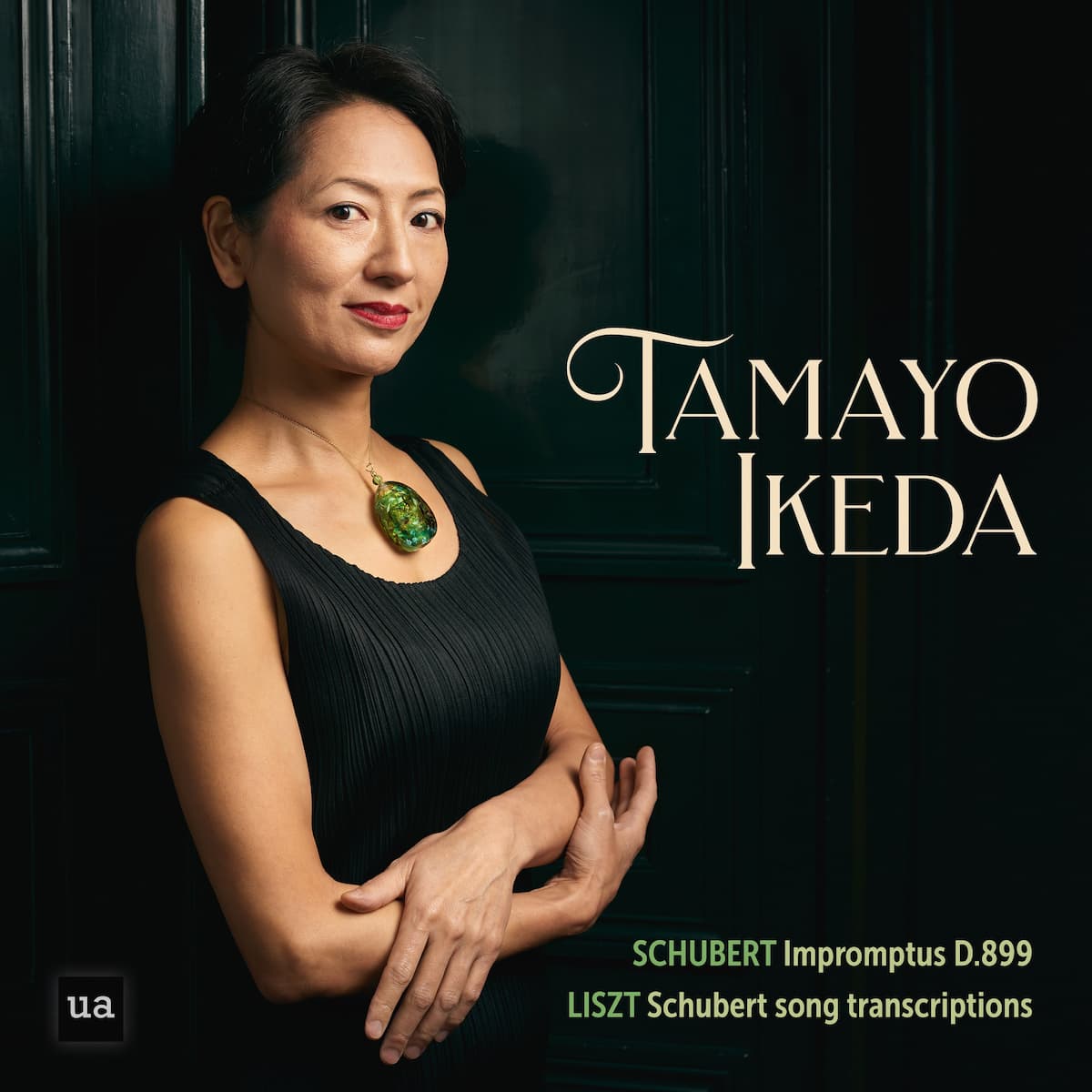

© Ulysses Arts

Liszt transformed some six of Schubert’s lieder into piano works. He was well aware of Schubert’s skill at song, saying once that ‘In the brief space of a song, Schubert makes us spectators of rapid but deadly conflicts.’ Children are stolen by mystical beings, men commit suicide because their lover prefers another, and so on. Schubert’s drama is often overlooked in the sheer joy of his melodies.

Schubert was the elder by 14 years and Liszt was only 17 when Schubert died, and Liszt held Schubert in particular regard. In some ways, by co-opting Schubert, Liszt was able to change the vision of the virtuoso being merely superficial and brilliant. Now he could take those deeper, darker stories and add his own light on top.

When you listen to Liszt’s version of Schubert’s own work for virtuoso pianist, Erlkönig, you have a double hearing load: the singer has to portray the 4 characters (narrator, child, father, Erl-king) through voice characterizations. Matter of fact for the narrator, light but frightened for the child, reassuring for the father, and enticing for the Erl-king. For the pianist, he has to make all those characterizations work all through the keyboard. Even though both hands are taken up with the horse’s motion, the other voices, all except the father’s played in the right hand, have to remain distinct.

Franz Liszt: 12 Lieder von Franz Schubert, S. 558: 4. Erlkönig

Because maintaining the different voices was so important, the text was added to the first edition score.

To change the mood completely, we also have Liszt’s transcription of ‘The Miller and the Brook’ from Die schöne Mullerin, where the poor apprentice miller has given up completely and gently drowns himself in the one constant he’s had in his time at the mill. The quiet sense of tragedy here is not deflected by trying to understand or remember the text but it has given a beauty in its own right.

Franz Liszt: Müller-lied, S. 565: No. 2: Der Müller und der Bach

In this new recording by Tamayo Ikeda, she not only plays the most significant of the Liszt-Schubert transcriptions but also includes the Schubert Impromptus, D. 899. These works were part of Liszt’s regular repertoire. Written in 1827, these works, as a whole can be imagined as a very large sonata spread out over 4 sections. No. 3, which can be imagined as the slow movement (andante in tempo versus the others’ allegro or allegretto tempos), sings at the piano.

Franz Schubert: 4 Impromptus, Op. 90, D. 899: No. 3 in G-flat major, andante

Liszt so loved these works that he published them in a new edition in 1868, adding fingerings and pedal markings to make them easier for others to play.

Tamayo Ikeda

This beautiful recording by Tamayo Ikeda is released on Ulysses Artists recordings. In an interview, Ikeda spoke about why Schubert and Liszt and why now. ‘After my tumultuous life and the pandemic, and without being able to play in front of an audience for a long time, I needed Schubert’s music terribly. His music consoled me with its sincerity. As I cannot sing, I made my piano sing.’ This is how many people feel in the waning days of COVID – we need a bit of consolation, a bit of excitement, but, above all, sincerity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter