A good many commentators consider Martha Argerich the greatest living pianist today. While such statements are always debatable, it is difficult to think of a more universally loved and respected musician. Her performances and recordings are as inward as they are vital, “of a unique musical intuition and charisma.” In addition, Argerich is well known for her generosity, humility, openness and authenticity. She has long encouraged young pianists, and her openness as a person “can certainly be perceived in her music making.”

A good many commentators consider Martha Argerich the greatest living pianist today. While such statements are always debatable, it is difficult to think of a more universally loved and respected musician. Her performances and recordings are as inward as they are vital, “of a unique musical intuition and charisma.” In addition, Argerich is well known for her generosity, humility, openness and authenticity. She has long encouraged young pianists, and her openness as a person “can certainly be perceived in her music making.”

Martha Argerich as a kid

Born on 5 June 1941 in Buenos Aires of Catalonian and Jewish ancestry, Argerich showed precocious talent as a child. She started piano lessons at the age of three with Ernestine de Kussrow, and continued her studies with Vincenzo Scaramuzza at age five. She performed her debut concert at the age of eight, playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto in C Major and Bach’s French Suite No. 5. In order to accommodate her meteoric musical rise, the Argerich family moved to Europe in 1955.

Argerich/Barenboim: Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1

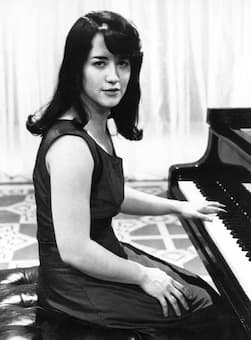

Martha Argerich, 1962

Argerich continued her studies with Friedrich Gulda in Vienna, whom she describes “as one of her major influences.” She made her first big splash at the age of sixteen, winning both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition within three weeks of each other in 1957. Argerich recorded her debut album for Deutsche Gramophone in 1960, including the Prokofiev Toccata and Liszt’s Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody. This release drew the admiration of Horowitz and “alerted everyone to an extraordinary technique and temperament… her early playing is notable for the creative tension that comes from pushing the music beyond any safety net.” She approached Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli for lessons, but despite being his student for well over a year, she only had four lessons. Michelangeli articulated this clear mismatch of personalities and musical outlook when he was asked what he had done for Argerich. Apparently Michelangeli replied, “I taught her the gift of silence.” She moved to New York, and tried unsuccessfully to meet and study with Horowitz.

Argerich Plays Bach’s Partita No. 2

Argerich at the 7th Chopin Competition

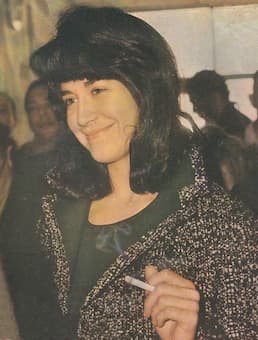

Following her early successes, Argerich had a deep personal and artistic crisis. At the age of 21 she stopped playing the piano altogether, and considered a career as a secretary or doctor. She became pregnant by the composer and conductor Robert Chen. They hastily married, but were separated before their daughter Lyda Chen was born. Argerich credits Anny Askenase, the wife of Stefan Askenase, with encouraging her return to the piano. She played her London début in 1964, and in 1965 entered the International Chopin Competition in Warsaw. She won the competition seemingly without breaking sweat with free-spirited performances that were described as “volcanic.” And while her aversion to the press and publicity has resulted in her remaining out of the limelight for most of her career, her determination to constantly strive for a better understanding of music has been relentless. “She works tremendously hard,” a colleague explains. “She has experience, knowledge, understanding, all of these, of course. But the key point is that she never relies on established habits or routine, and never plays safe.”

Argerich Plays Schumann’s Piano Quintet

Martha Argerich, 1965

Argerich seems to have the elusive gift of playing as if she is making the music up on the spot. “To convey this degree of spontaneity, to give the impression that you’re creating something in the heat of the moment, requires two things. First, such freedom takes consummate musical understanding and mastery of an idiom. Some musicians seem to live the music as they play it, while others strive for a preconceived ideal where, all being well, one performance will be as close to that ideal as the next. Artists like Martha Argerich still have a clear vision and a fully formed interpretation, and are no less perfectionist, but they embrace a more responsive creativity and the possibility of making a connection that is unique to a specific moment.”

Argerich Plays Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit

Argerich’s ability to summon a range of pianistic colors is as uncanny as it is miraculous. Her playing is full of subtlety and finesse, “and her range of color, her use of the pedal, and a sense of beauty of sound is quite unique.” This seems particularly true in piano and pianissimo passages, which “sound brilliant but tender, like a diamond, sharp but still warm.” In addition, her performances are almost improvisations. According to a colleague “it’s about intuition; when you have a score that you have learnt, you have to get beyond that and play it as if the music is just coming into your head at that moment, like an improvisation.”

Argerich’s ability to summon a range of pianistic colors is as uncanny as it is miraculous. Her playing is full of subtlety and finesse, “and her range of color, her use of the pedal, and a sense of beauty of sound is quite unique.” This seems particularly true in piano and pianissimo passages, which “sound brilliant but tender, like a diamond, sharp but still warm.” In addition, her performances are almost improvisations. According to a colleague “it’s about intuition; when you have a score that you have learnt, you have to get beyond that and play it as if the music is just coming into your head at that moment, like an improvisation.”

Martha Argerich, 2015

Martha Argerich’s fire still burns bright and her playing is as fresh and inventive as ever. Although she worries about memory lapses, the fact “that she has not lost any of her technical facility is testament to the most relaxed, unlimited technique that you could imagine.” As a colleague remarked, “with Argerich you don’t feel that there is any fundamental difference in what she can do now compared to when she was young… this seem absolutely unique.” Argerich still plays the piano with the energy and effervescence that have defined her career from the very beginning. “Her music, her life and her personality do not work in isolation; they are inextricably linked to each other.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Argerich Plays Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 3