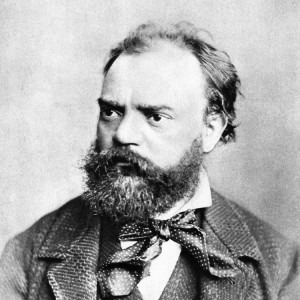

Antonín Dvořák

When Antonín Dvořák returned from the US in 1896, he took poetic ballads from the Czech poet Karel Jaromír Erben as the basis for a set of symphonic poems, including The Water Goblin, The Noonday Witch, The Wild Dove, and The Golden Spinning Wheel. His cantata, The Spectre’s Bride was also based on Erben’s work.

The Golden Spinning Wheel sounds like it should be a story, something like Rumpelstiltskin but instead, it’s a tale of jealousy and hidden murder and murder discovered.

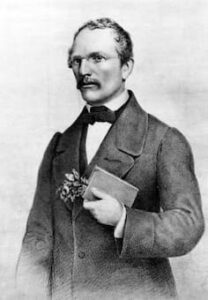

Karl Eben

While hunting in the forest, the young king sees and falls in love with Dornička. Her stepmother, jealous that it wasn’t her daughter chosen, kills Dornička on the way to bringing her to the palace and hides her in the woods, keeping her hands, feet and eyes. Dornička’s stepsister, who resembles Dornička, substitutes for her and marries the king. The king goes off to war, asking his new bride to spin until he returns. In the meantime, a magician has discovered Dornička’s body and brings her back to life, exchanging a magic golden spinning wheel, a golden distaff, and a golden spindle for the missing parts that the stepsister has charge of. The king returns and as his false wife spins, the golden spinning wheel reveals to him the tale of the gruesome crime. The king goes to the forest and finds his beloved Dornička, alive and waiting for him. This is where Dvořák ends his story. In Erben’s ballad, the stepmother and stepsister are devoured by wolves and the golden spinning wheel vanishes.

The opening of the piece evokes not only the hunting party but also the steady churn of the spinning wheel in the lower strings.

Antonín Dvořák: The Golden Spinning-Wheel, Op. 109, B. 197 ( Czech Philharmonic; Charles Mackerras, cond.)

Spinning wheel

Dvořák used Erben’s ballads as a way of invoking his Czech identity again. Erben’s stories were highly moral, and when those moral principals were violated, their transgressor had to pay. Most of the Erben sources that Dvořák used came from his 1853 collection Kytice z pověstí národních (A Bouquet of Folk Legends). Kytice, as it’s more commonly known, contained 12 ballads, with a further one added in 1861. The collection is considered an important part of the Czech Romanticism movement of the mid-19th century.

Although these symphonic poems by Dvořák are not his best known works, they are an important connection to his Czech roots and are an important contribution not only to program music but also nationalistic music in the 19th century.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter