The 19th century and the increasing wealth in the middle class brought refinements to the front parlour of the home, most notably, the large black monster known as the piano. Children were pressed into years of piano study so that they perform before visitors, showing off their musical skills.

Of course, we know that most pianos were set aside as new technologies swept through, and then, finally, when the radio made music available over the airwaves, the piano was permanently sidelined. However, the 19th-century interest in technology, which enabled the creation of mass-produced pianos, also led to the development of player pianos.

The first practical pneumatic mechanism that could play your piano for you was created in 1896, and so, under the hands of Edwin S. Votey, the Pianola was born. This wasn’t a mechanism in the piano, but rather a box that was rolled up to the front of the piano.

Walter Donaldson: Whoopie: Makin’ Whoopie (piano player)

Pianola, closed view, 1901 (National Museum of American History)

When the covering doors were opened, the foot pedals were exposed, and the centre lid could be opened to insert the paper roll of music.

Aeolian Pianola, showing foot pedals and piano roll access, 1901 (National Museum of American History)

When placed in front of an 88-key piano, and its 65 felt-covered fingers were aligned with the proper keys, the player would sit at the Pianola, pump with his feet (like one would have done with small home organs like the harmonium), air would be generated, and the holes in the paper would guide the fingers to the right keys. You’ll also see at the bottom controls for the piano’s pedals.

Aeolian Pianola, back view with key fingers, 1901 (National Museum of American History)

Edwin Votey created his first Pianola in his workshop in Detroit and then joined the already existing Aeolian Company, which was a joint venture between the Mechanical Orguinette Company of New York, and the Automatic Music Paper Company of Boston.

Hubert Parry: The Frogs (Aristophanes) (arr. for pianola) (Rex Lawson, pianola)

The Orguinette (or organetto) was an instrument for playing music on perforated disks made of paper, cardboard, or metal. It was operated by mechanical bellows that were either hand- or foot-operated.

The Ariston Organetto

The organetto in operation

We can see that the basis of the Pianola, a mechanism that could read music on paper via air pressure, was already around. Votey’s extension of the mechanism to drive mechanical fingers meant that the sound was better than could be produced in the organetto box and that the entire piano repertoire could be accessible.

By 1903, the Aeolian Company had more than 9,000 rolls available for sale, adding some 200 new titles per month. By 1908, the 65-key piano roll was replaced by the 88-key roll. In a clever bit of back design, the 66-key pianolas could play the 88-key piano rolls (a rare consensus agreement meaning that there wasn’t a format war between old and new instruments).

Ruggero Leoncavallo: La bohème, Act II – Valse de Musette (Ruggero Leoncavallo, Welte-Mignon Reproducing Piano)

The music rolls placed in the piano were created by a technician working from a score. Once the original was made and tested, the commercial rolls could be copied from it.

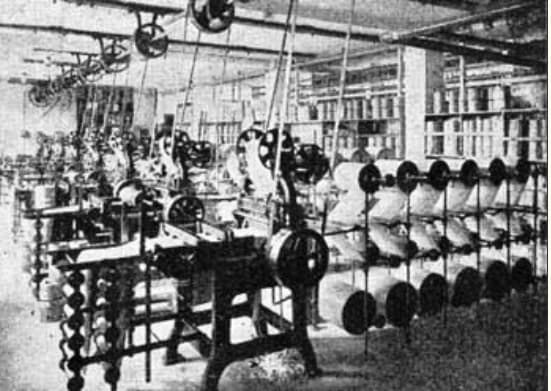

Hupfeld Animatic Roll Perforating Machines, Leipzig, 1920s

Player piano rolls were fit into the piano with end clips and then attached to the mechanism with a little ring.

Piano roll with ring attachment (National Museum of American History)

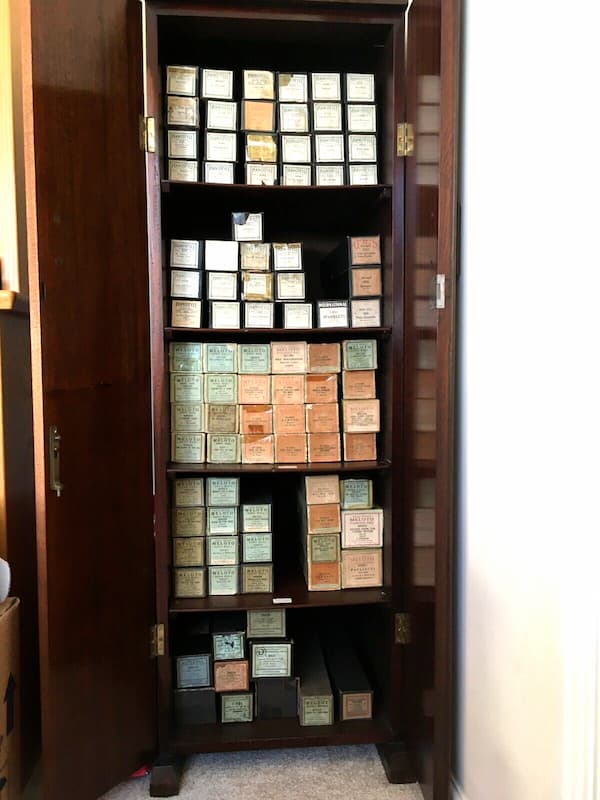

They were stored in specially designed boxes, with the word’s name on the small end of the box.

Piano roll box

Piano roll boxes in their cabinet

One of the problems with the piano rolls was that they ran at a constant rate, and the things that make piano music evocative, such as phrasing, rubato, dramatic pauses, etc., couldn’t be controlled by the roll.

The next development in the player piano industry came from Germany. Edwin Welte developed a player that was more subtle in that it could preserve all the original articulations of the pianist. Instead of armies of workers creating piano rolls by hand, manufacturers could get leading composers and performers to create the original rolls. Consumers could then, literally, take Edvard Grieg, Alexander Glazunov, or Ignacy Paderewski home to play.

Alexander Glazunov: Vremena goda (The Seasons), Op. 67 (version for piano) – L’Ete: Barcarolle – Variation (Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov, Welte-Mignon Reproducing Piano)

The Welte Company already had a background in making mechanical musical instruments, but it was the creation of the Reproducing Piano which ‘automatically replayed the tempo, phrasing, dynamics and pedalling of a particular performance, and not just the notes of the music, as was the case with other player pianos of the time’ as its catalogue noted.

The Welte-Mignon Vorsetzer (Push-up) in place before a grand piano

This recording on the Welte-Mignon was made by Carlo Zecchi in 1926.

Igor Stravinsky: 3 Movements from Petrushka – No. 3 La semaine grasee (The Shrove-tide Fair (Carlo Zecchi, Welte-Mignon reproducing piano)

One of the interesting details about piano roll creation was that they could be edited. There’s a letter from Paderewski to the Aeolian company asking them to ‘tidy up some of his arpeggios’ and a report that Stravinsky’s arrangements of his works for player piano couldn’t be played by a normal pianist because more than 10 keys were being called for at a time.

Percy Grainger and W. Creary Woods editing a Duo-Art Music Roll, New York, c. 1915

As can be seen in the Grainger picture, the mechanisms, either for player pianos or reproducing pianos could be fit into the pianos themselves. There was no need for a separate push-up mechanism.

Steinway-Welte reproducing piano, 1919

The rise of jazz and the fox-trot made the player piano the instrument for popular music making and the reproducing piano was dedicated to classical music. This split rapidly led to the decline of the classical catalogues, by the end of the 1920s. Some of the last reproducing piano recordings with name artists were made in late 1920s.

Pinetop Smith: Boogie Woogie (player piano)

The two primary developments that killed those evenings staying home gathered around the pianola were the radio and, later, the cinema. After WWII, the greater availability of electricity meant that new instruments for home amusement were available. Many foot-pump player pianos were relegated to storage, replaced by new boxes of sound.

There was a resurgence of the player piano in the 1950s and again in the 1980s. Composers such as Conlon Nancarrow used his works for the player piano to stretch music making into non-human realms – writing music that humans could not play due to the speed, the way the hand had to stretch, or the number of keys used at one time.

Conlon Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 3a (Conlon Noncarrow, Ampico player piano)

The upswing in interest has resulted in both the preservation of player pianos and their music. A number of both plain player-piano rolls and the more refined reproducing piano rolls are again available for your listening pleasure…but now played through your CD player or streamed online.

Celebrate Player Piano Day with a blast from the past!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter