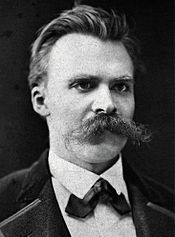

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Das zerbrochene Ringlein

Piano Sonata in G Major

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” This most widely quoted statement originating with Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900) first appeared in the 1882 publication Die fröhliche Wisssenschaft (The jolly Science) and is restated in Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus spoke Zarathustra). Naturally, this statement questioning the value and objectivity of truth — essentially looking at God as a historical process — spawned a number of philosophical and theological movements. But Nietzsche, who also wrote numerous texts on morality, contemporary culture, philosophy and science, never really trusted the written word. “In comparison to music,” he wrote, “all communication through words is shameless. The word diminishes and makes stupid; the word depersonalizes, the word makes what is uncommon common.” This love and reverence for music was fostered from an early age.

Descended from a family of pastors where music and theology traditionally went hand in hand, young Friedrich was an accomplished pianist and organist by the time he reached the age of seven. At that time, he was capable of playing several Beethoven sonatas and transcriptions for Haydn’s symphonies and was naturally skilled in the way of improvisation. When he was fourteen, he wrote, “All qualities are united in music: it can lift us up, it can be capricious, it can cheer us up and delight us, nay, with its soft, melancholy tunes, it can even break the resistance of the toughest character. Its main purpose, however, is to lead our thoughts upward, so that it elevates us, and even deeply moves us. All humans who despise it should be considered mindless, animal-like creatures. Let music, this most marvelous gift from God, remain forever my companion on the pathways of life.” In his Reminiscences on my Life, penned at age fourteen, Nietzsche painstakingly listed his writings and his compositions, of which he had already completed 46 by 1858! These early works are Lieder settings of poetry by Klaus Groth, the Hungarian poet Sándor Petöfi, Pushkin and Hoffmann von Fallersleben, all composed “in a kind of barbarous frenzy, as the demon of music took hold of me.” In terms of composition, Friedrich was essentially self-taught, describing himself as “a wretched youth who tortured his piano to the point of drawing from it cries of despairs, who with his own hands heaves up in front of himself the mire of the most dismal gray-brown harmonies.” When he turned sixteen, he started to compose a Christmas oratorio, which was never finished. However, he would develop several themes for later use in subsequent compositions. “I look for words for a melody that I have, and for a melody for words that I have, and these two things I have don’t go together, even though they come from the same soul. But such is my fate.” Many Nietzsche Lieder pay homage to Robert Schumann in attempting to preserve the equilibrium between formal requirements and subjectivity. Yet, there are additional points of contact between Schumann and Nietzsche. In 1852, Schumann had composed his dramatic poem Manfred, an adaptation of Lord Byron’s supernatural poem. Twenty years later — Nietzsche presented his Manfred Meditation for evaluation to Hans von Bülow, famous conductor and son-in-law to Richard Wagner.

Bülow was not impressed, and wrote, “this music is the most extreme in fantastic extravagance and the most unsatisfying and most anti-musical composition I have seen in a long time. Is this a joke that deliberately mocks all rules of tonal harmony, of the higher syntax as well as of ordinary orthography? In musical terms, this piece is the equivalent to a crime in the moral world, with which the musical muse, Euterpe, was raped. If you would allow me to give you some good advice, just in case you are actually serious with your aberration into the area of composition, stick with composing vocal music, since the word can lead the way on the wild sea of tones. I apologize, esteemed Herr Professor, of having thrown such an enlightened mind as yours, into such regrettable piano cramps.” Nietzsche did try to justify himself. “As for my music,” he writes, “I only know that it allows me to master a mood that unsatisfied, would perhaps produce even more damage. If music serves only as a diversion or a kind of vain ostentation, it is sinful and harmful. Yet this fault is very frequent; all of modern music is filled with it.” During his time as professor of Philosophy at Basel University, Nietzsche became a close personal friend of Cosima and Richard Wagner, then living in Swiss exile. It has been suggested that he fell in love with Cosima Wagner; he certainly composed some music for her. Listening, performing and composing music became an unconsciously philosophical activity for Nietzsche, who suggested that “sound allowed me to say certain things that words were incapable of expressing.” In the end, Nietzsche famously wrote, “We have art so as not to die from the truth.”

Bülow was not impressed, and wrote, “this music is the most extreme in fantastic extravagance and the most unsatisfying and most anti-musical composition I have seen in a long time. Is this a joke that deliberately mocks all rules of tonal harmony, of the higher syntax as well as of ordinary orthography? In musical terms, this piece is the equivalent to a crime in the moral world, with which the musical muse, Euterpe, was raped. If you would allow me to give you some good advice, just in case you are actually serious with your aberration into the area of composition, stick with composing vocal music, since the word can lead the way on the wild sea of tones. I apologize, esteemed Herr Professor, of having thrown such an enlightened mind as yours, into such regrettable piano cramps.” Nietzsche did try to justify himself. “As for my music,” he writes, “I only know that it allows me to master a mood that unsatisfied, would perhaps produce even more damage. If music serves only as a diversion or a kind of vain ostentation, it is sinful and harmful. Yet this fault is very frequent; all of modern music is filled with it.” During his time as professor of Philosophy at Basel University, Nietzsche became a close personal friend of Cosima and Richard Wagner, then living in Swiss exile. It has been suggested that he fell in love with Cosima Wagner; he certainly composed some music for her. Listening, performing and composing music became an unconsciously philosophical activity for Nietzsche, who suggested that “sound allowed me to say certain things that words were incapable of expressing.” In the end, Nietzsche famously wrote, “We have art so as not to die from the truth.”

More Anecdotes

- Bach Babies in Music

Regina Susanna Bach (1742-1809) Learn about Bach's youngest surviving child - Bach Babies in Music

Johanna Carolina Bach (1737-81) Discover how family and crisis intersected in Bach's world - Bach Babies in Music

Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782) From Soho to the royal court: Johann Christian Bach's London success story - A Tour of Boston, 1924

Vernon Duke’s Homage to Boston Listen to pianist Scott Dunn bring this musical postcard to life