We musicians just want to make music. We are willing to self-destruct if need be. But the goal is to re-create great music with ease and expressiveness. It’s vital to keep in mind that our violins, cellos, flutes and trombones are only half the musical product. They can do nothing until they interact with our physical, emotional and very human beings.

It is now widely known that it can hurt to play. Playing too much, too intensely, over weeks, months and years can do cumulative damage. Perhaps right now you can launch into any concerto or difficult orchestral work, any time no problem, and pretty much nail everything. Due to a wear and tear in your muscles that occurs over time, however, you may become less able to do these things and you may be at a higher risk for injury. Overuse is a loose term applied to several conditions in which body tissues have been stressed beyond their biological limits. These disorders of the musculoskeletal system can affect bones, joints and such soft tissues as ligaments, tendons and muscles.

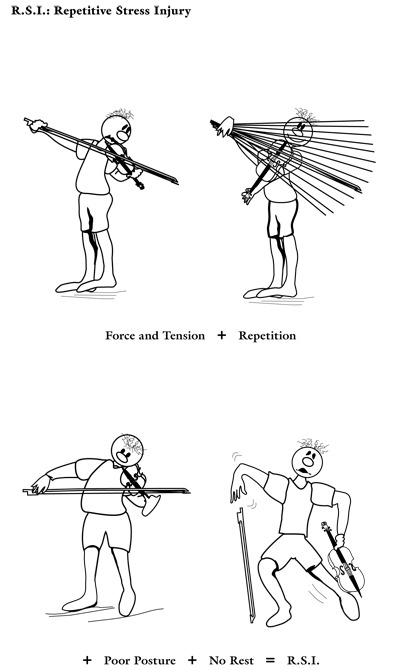

Repetitive action, especially when combined with poor posture, excessive force and stress, brings about overuse injuries. And we must take into consideration the intense and competitive nature of our wonderful profession. We’re all trying to play bigger and louder and faster. That adds up! Just as elite athletes can sustain an injury we, too, can be injured, even if we’re doing everything right.

Even we don’t realize the repetition we subject ourselves to on a daily basis:

Ravel’s Bolero brings the house down every time it’s played. The snare drum player always receives an ovation, well deserved. In the fourteen-minute work, the snare drum player repeats a 24-note pattern nonstop from beginning to end. The piece is 430 measures. That’s 5,144 arm strokes. What a feat! Add to that the control necessary to start almost inaudibly at pianissimo and ever-so-gradually increase in volume over fourteen minutes to the piece’s rousing fortissimo conclusion. It requires intense concentration and physical control to play unwaveringly steady in rhythm from start to finish.

In Adam’s Harmonielehre the first 94 bars of Part III have approximately 976 repeated eighth notes for the flute piccolo, piano, harp and clarinet. This during a mere fraction of the work!

Recently, after playing a passage over and over of an obscure work of Sibelius entitled Oceanides I counted the bow strokes: 27 per bar. I knew it was tiring, but this was ridiculous. In 22 measures played in one and a half minutes, there were 589 bow strokes! I approached our Maestro and said “Osmo, from here to here we have to perform 589 bow strokes!” He appeared taken aback for a moment and then replied “Thank you for counting!”

I think I make my point. What the human body can do is incredible! On a daily basis we demand these feats of athleticism, precision, coordination and beauty from our bodies, and yet we are dismayed and astonished when they let us down. What does all this repetition mean, anatomically speaking?

Overuse is the term applied when any tissue, bone, joints or soft tissue such as muscle, ligaments or tendons are stressed beyond their anatomical or physiological limit.

In musicians, overuse is usually the result of multiple factors, which can include excessive force, repetition, high intensity, awkward postures and poor technique. It’s a vicious cycle. Muscles that are overused have exhausted their endurance capacity. Muscles that are fatigued become less efficient and less responsive; thus we try to play with more force. This results in more fatigue and tension, then inflammation and increasing pain and diminishing returns.

Overuse injuries require many weeks of recovery. Players who will not or cannot allow sufficient healing are headed for disaster. Overuse injuries can become chronic. The scenario is all too common.

Loose vs. Tight

Musicians come to the profession in all shapes and sizes. While “tight” or tense individuals may become injured due to shortened muscles, “loose” individuals are vulnerable as well. Joint laxity, or hypermobility (otherwise known as “doublejointedness”), have to work extra hard to prevent knuckles or joints from “buckling” or collapsing. The extra force these players must use to keep fingers rounded puts these musicians at risk for an overuse injury.

Examine your technique to eliminate any unnecessary tension. Get out of awkward postures as soon as you can. Avoiding holding stretches and large chords Do not slam fingers down. Release them as much as possible. Avoid mindless repetition while practicing.

Follow my Five Essential Practice Rules :

– Warm up.

– Take breaks.

– Vary your repertoire.

– Increase your practice load gradually.

– Reduce your practice intensity prior to performance.

How do you know if you are susceptible to an injury? Take my injury susceptibility quiz at www.playinglesshurt.com and find out if your style of playing puts you at risk.

“This is an excerpt from Playing (Less) Hurt by Janet Horvath, published by Hal Leonard Books”