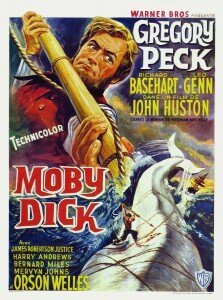

Hollywood has always been eager to bring epic novels to the silver screen. And such was the case when they took on Moby Dick in 1956. Ray Bradbury, who confessed to director John Huston that he had “never been able to read the damned thing,” wrote the screenplay. Gregory Peck was hired to portray Captain Ahab, and in a major surprise, the English composer Philip Sainton (1891-1967), who had never scored a film before, was selected to furnish the music.

Hollywood has always been eager to bring epic novels to the silver screen. And such was the case when they took on Moby Dick in 1956. Ray Bradbury, who confessed to director John Huston that he had “never been able to read the damned thing,” wrote the screenplay. Gregory Peck was hired to portray Captain Ahab, and in a major surprise, the English composer Philip Sainton (1891-1967), who had never scored a film before, was selected to furnish the music.

Gregory Peck as Catpain Ahab

And while Bernard Herrmann had been considered, it was felt that the most important quality for the composer of Moby Dick “was a clear-cut empathy with the sea and its ever-changing moods and perplexing mysteries.” Sainton cautiously approached his assignment, and between January and April 1955 he worked on the themes and motifs for the film. In the end, he wrote a most remarkable score brimming with vitality that far exceeds the demands of background music. It has even been suggested that Sainton “produced one of the most virile sea scores ever composed.”

Tōru Takemitsu

For Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996), “Music is either sound or silence. As long as I live I shall choose sound as something to confront a silence. That sound should be a single, strong sound.” He considered musical form a liquid entity in which musical changes happen as gradual as the tides. Known for his exploration of Japanese instruments in a contemporary Western musical context, he particularly focused on works for the “biwa” (Japanese lute), and the “shakuhachi” (Japanese flute). And these instrumental selections are mirrored and transformed in his Toward the Sea, originally written for alto flute and guitar in 1981. In all, he produced three versions of Toward the Sea, and the movement titles suggest the epic novel of Herman Melville, none more tellingly than the second movement titled “Moby Dick.” Takemitsu considered the composition “fragments thrown together, as if in a dream, creating imaginary soundscapes.”

Toru Takemitsu: “Moby Dick,” Umi e (Toward the Sea)

Richard Brooks

It is in the waters off the coast of Japan that Captain Ahab first confronts and is ultimately defeated by the great white whale. That location is no accident, as Melville creates an elaborate geographical roadmap intended to disclose his complicated thematic intentions. We learn of these places through the text narrator Ishmael, who describes in significant details the Cape of Good Hope, Java Head, the Bashee Isles, the Arsacides, and Lima, Peru. But Melville was not focused on exotic backdrops, but as a keen analytical observer recognized in the world around him an American pattern of imperialism. To him, America was not merely concerned with continental expansion, but “angling for expansion on a global scale.” While most literary critics and historians point to the Spanish-American War of 1898 as the date for American imperial ambitions, Melville recognized that global reach in the 1830s. In the second Act of his opera Moby Dick, Richard Brooks musically takes us into the Japanese Sea. To be sure, imperialism is not on his mind as his grand soundscapes detail a much more personal history.

Richard Brooks: Seascape, “Overture to Moby Dick”

Laurie Anderson

The singer-songwriter Laurie Anderson is without doubt the reigning performance artist of our time! A daring and creative pioneer who addresses universal themes in the vernacular of the commonplace, Anderson seamlessly combines her extraordinary flair for multimedia and visual artistry with her considerable talents as a composer and musician. Anderson is widely considered a groundbreaking leader in the use of technology in the arts. She has invented several experimental musical instruments, including the “Tape-bow violin” and the “Talking Stick.” When Anderson reread Moby Dick it became a complete revelation. “Encyclopedic in scope, the book moved through ideas about history, philosophy, science, religion and the natural world towards Melville’s complex and dark conclusions about the meaning of life, love, and obsession… It is also a tour de force in narrative style, as Melville tells his stories in hundreds of shifting voices, as botanist, lawyer, preacher, historian. These narrative styles and forms of address, from dry to dreamy, morph rapidly.” Anderson’s take on Melville emerges in the hugely ambitious techno opera Songs and Stories from Moby Dick. Critics called it a “more smoothly integrated package than many a contemporary theater piece or opera.”