Violet Gordon-Woodhouse changed how listeners approached and appreciated Baroque music. She helped spur the revival of the harpsichord and Baroque Era composers, making a big contribution to the beginnings of the historical performance practice movement, which is still going strong today.

But if she’s remembered today, it tends to be for her salacious personal life.

Maybe it’s time for a reappraisal. Here’s an introduction to the life and career of the fascinating harpsichordist Violet Gordon-Woodhouse.

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse’s Turbulent Childhood

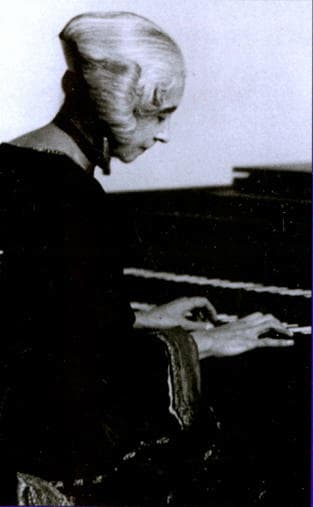

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse was born Violet Kate Eglinton Gwynne on 23 April 1872 in London, the fourth of seven children.

Her family was wealthy and boasted not only a tony London address, but an estate in Sussex, too. She spent her childhood being shuttled back and forth between the family homes.

Her father James Gwynne was a gruff Scottish engineer and landowner with a sharp temper and an overpowering personality.

Fortunately, her mother, Mary, was a more nurturing influence. Mary Gwynne was a pianist, and she made sure that Violet was able to escape their turbulent home life by studying piano and attending various musical events.

From an early age, it was clear that Violet had inherited her mother’s musical talent. As she grew up, the two became especially close. Eventually, Violet’s talent marked her out as the family’s golden child, who was relatively protected from James’s anger.

After studying piano with her mother, she began taking lessons from renowned teacher Oscar Beringer, who would produce some famous British pianists of the era. She began dreaming of a career as a soloist.

Her father, however, discouraged those dreams. He believed that his daughter becoming a professional touring pianist would be unseemly and scandalous and reflect poorly on his ability to provide for his family.

Falling In Love With Her Remarkable Husband

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse, circa 1900

Like most young women of her class and era, and with no career in sight, starting in her late teens, Violet Gwynne began searching for a husband who would help improve or sustain her social and economic position.

In 1893, when she was twenty-one, she met a promising marriage candidate when Sir Henry Charles Gage, set to become the 5th Viscount Gage, proposed to her. There was a nearly twenty-year age difference between the two, but she accepted anyway.

However, when her mother explained the mechanics of sex to her, Violet was horrified. She refused to go through with the marriage and broke off the engagement.

Two years later, still single, she went to a house party thrown by her brother. While there, she met one of his friends from Cambridge, a man named Gordon Woodhouse. A rumor eventually spread that a hunting accident had affected his ability to have a physical relationship, but Violet didn’t mind. Within weeks, the two were married.

The marriage to Woodhouse served two important purposes. It allowed her to finally leave the household of her domineering father, and it gave her freedom to pursue her musical studies on her own terms.

And it didn’t hurt that Woodhouse adored his new wife. He indulged her every whim, and went so far as to legally change his name to the clunky moniker John Gordon Gordon-Woodhouse, simply because Violet liked the sound of the hyphenated name Violet Gordon-Woodhouse.

He even quit his job to care for the household so she could concentrate on her art. Consequently, Violet found herself in a highly unusual situation for her era: she had a husband playing the supportive domestic role that so many women throughout musical history have been forced to play for male geniuses.

She wouldn’t squander the opportunity.

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse Plays Bach

Falling in Love with the Harpsichord

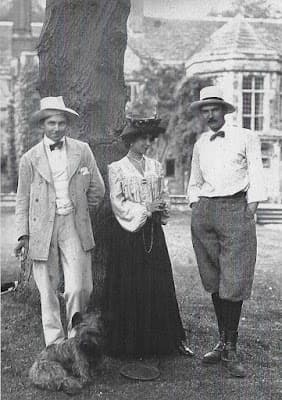

Violet with Gordon and Bill at Southover Manor

In 1896, she attended a concert by a man named Arnold Dolmetsch and made a life-altering artistic discovery. Dolmetsch was a French keyboardist and builder of replica historic instruments, and he was trying to spread the gospel about the long-forgotten artistic possibilities present in these antique-styled instruments.

Violet immediately fell in love with everything about the harpsichord. The piano fell by the wayside, and the harpsichord became her voice.

Three years later, in 1899, she played Bach’s Concerto for Three Harpsichords at a public concert in London. The players on the other two instruments were Dolmetsch and his wife.

A string of professional successes followed. In 1919, Delius wrote a harpsichord piece especially for her. No less a figure than Ferruccio Busoni, after hearing her play, declared her “one of the greatest living keyboard artists.” And in 1920, she signed a four-year recording contract, becoming the first person ever to record on the harpsichord, male or female.

Frederick Delius – Dance for Harpsichord

The Legendary Ménage à Cinq Begins

Violet had an unusual personal life, even by modern standards. That personal life was about to get even more complicated, and, sadly, it ended up often eclipsing her artistic accomplishments.

It started in 1899, when a man named William Barington, heir to a viscount, came to visit the Woodhouses. Within three days, he had fallen in love with her.

Violet had feelings for him, too. She, her husband, and Barington discussed what to do. Barington was invited back to their home. Finally, after months of visits, he just moved in, risking scandal and accepting the horrified judgment of his family, who cut him off. He ended up becoming the love of Violet’s life. Their relationship was physical, but there’s no indication that this ever bothered Woodhouse.

The set up was unusual enough in Edwardian England, but soon circumstances became even more unusual. By 1903, a “witty barrister” named Max Labouchere and a “highly musical cavalry officer” named Dennis Tollemache also joined the household. The situation had turned into a ménage à cinq!

Labouchere helped Violet with her general education, while Tollemache, who had initially fallen in love with her playing when he was just a boy, was an important sounding board about musical matters.

To the horror of many, these five adults made their unconventional web of relationships work, and it appears that life was quite idyllic for all of them during this time.

Women weren’t immune to Violet’s charms, either. Queer composer Ethel Smyth once pointedly gifted Violet a book of poetry by Sappho, and lesbian writer Radclyffe Hall dedicated a book of poetry called The Forgotten Island to Violet. Given Violet’s fondness for breaking the rules, it’s possible that their friendships had a romantic element, too.

The Catastrophes of the Great War

Violet with Gordon, Bill and Max, taken by Dennis at Armscote

World War I proved to be devastating not just on a global level, but on a personal one, too. All of Violet’s partners except her husband fought in the war. Bill and Dennis survived, but both had shellshock, and Max died in the fighting. Even though he never saw combat, Woodhouse faced great financial losses. A spell had been broken, and things would never be quite the same again between the survivors.

To make matters worse, Violet’s father had died in WWI, and Violet was not included in the will. Money trouble ensued. It was around this time that she signed her pioneering recording contract, likely to help pay the bills.

A bizarre tragedy in 1926 ended up being a stroke of good luck for the members of Violet’s household. Two of Woodhouse’s aunts were murdered by their butler, and Violet and Woodhouse were the ones who ended up inheriting their estate. This stroke of good fortune (?) helped fix their money trouble, and perhaps kept her from needing to return long-term to the concert stage.

Violet Gordon Woodhouse’s Death and Legacy

Violet died on 9 January 1948. Her husband and Bill continued living together until 1951, which suggests that they were genuinely attached to each other in their own way.

Violet Gordon-Woodhouse was an important figure, not just because of the conviction with which she led her personal life, but because she was on the cutting edge of both historically informed performance practice and recording technology.

She was one of the first people to show the modern world what was possible on the harpsichord. To do that, she created a home environment that allowed her to become one of the great keyboard players of her era, discarding conventions that didn’t serve her interests, and finding partners who supported her.

A major reason why she isn’t better known today is her social class, and the fact that so many of her performances took place in private salons instead of on public stages.

But fortunately, her art survives through her extraordinary recordings. They paint a portrait of an independent artist who not only knew what she wanted – but who, unlike so many women artists of her era, was actually able to get it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter