Vincenzo Galilei

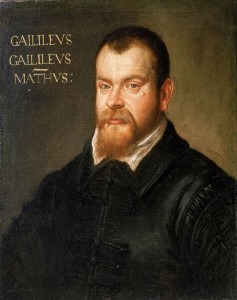

We all know that Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) is commonly known as the “Father of modern observational astronomy,” the “Father of Modern Physics,” and the “Father of Modern Science.” But did you know that his father, Vincenzo Galilei (1520-1591) was a famous lute virtuoso, composer and music theorist? His seminal experiments with pitch and string tension resulted in a system of tuning that helped to usher in the music of the Baroque. Vinzenzo hailed from the Tuscan village Santa Maria a Monte, and exhibited incredible musical aptitude from an early age. He was soon considered a lute virtuoso and earned a good living as a performing musician and teacher. By 1562, he had moved to the town of Pisa and married Giulia Ammannati, daughter to one of the noble families. Galilei was born in 1564, the first of seven children that also included Michelagnolo, who became famous as a lutenist and composer in his own right.

Professionally, Vincenzo traveled to Venice to study music with Gioseffo Zarlino, considered the foremost musical theorist of his day. Originally, Vincenzo accepted his teacher’s original view of the Ptolemy diatonic tuning system, but once he returned to Florence he became part of a group of composers, music theorist and scholars — subsequently termed the “Florentine Camerata” — under the auspices of the literary critic, writer and composer Giovanni de’Bardi. Bardi had been in touch with Girolamo Mei, the foremost scholar of ancient Greek drama and music, and was looking to restore the effect of ancient Greek music to contemporary practices. Vincenzo’s most famous musical treatises Dialogo della musica antiqua et della moderna (Dialog about Ancient and Modern Music), in which he condemns polyphony and suggests that “all corrupt and incomprehensible contemporary music should be replaced with an idealized version of the supposed music of the ancient time,” was squarely aimed at his famous teacher. In due course, the animosity between the two theorists blossomed into a genuine hatred of each other. The music-theoretical nature of their disagreement has been the subject of rather intensive and serious studies; for our purposes, it will suffice to say that Vincenzo combined the theory with the practice of music. Previously, the theory of music had been the exclusive domain of mathematical discussions on harmony and string ratios dividing the octave.

Galileo Galilei